Life in the REAL Happy Valley has all the light and shade you see in the TV version, reveals acclaimed author and Hebden Bridge resident HORATIO CLARE ahead of this weekend’s explosive series finale

Welcome to the thunderous Pennines, to the wheeling West Yorkshire skies and to the town that is uniting light and dark, good and evil and more than eight million television viewers in a mighty showdown: the series finale of BBC One’s Happy Valley tomorrow night.

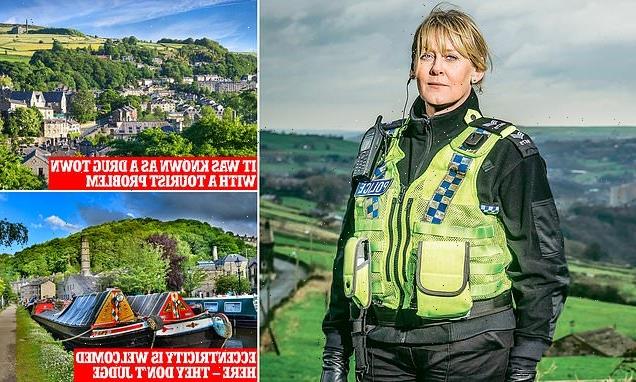

This is Hebden Bridge in the Calder Valley, my home for the past decade. It is a beautiful place wound around a confluence of moors and rivers — but it is a dark place, too, pounded by the weather, half-hidden from the sun in winter and carrying its own hard histories.

We moved here from Verona, Italy, for family reasons. The contrast between one of the brighter parts of Europe and the strikingly wet valley was comic. In bleak weather, it was savage.

‘By ‘eck, you’ve come a way!’ was our new neighbour’s verdict.

Hebden — ’Ebden, in local — half-way between Leeds and Manchester, has long been famous for its rugged beauty, its strong and diverse community and its history of creativity. (The poet Ted Hughes came from the area, and the grave of his wife, Sylvia Plath, overlooks the town.)

More than eight million television viewers are set to watch the mighty showdown of the series finale of BBC One’s Happy Valley tomorrow night

But at the moment, thanks to the BBC’s extraordinary northern noir, we are principally famous for the upcoming confrontation between Sergeant Catherine Cawood and Tommy Lee Royce, which is set — and filmed — around here.

Catherine (Sarah Lancashire) is Happy Valley’s battered and pithy heroine — often desperate, ever capable. Her nemesis is the abominable villain and charismatic murderer Royce, unforgettably played by James Norton. The show has pulled off one of those special moments of British television, when actors, script, setting and direction combine to make something for the ages.

The performances and dialogue — the latter the work of Huddersfield-born writer Sally Wainwright — are eerily truthful, and the effects on Hebden Bridge and our valley have been dramatic.

‘At 10pm for the past two Sundays, I’ve been too scared to go out of the house in case I see Tommy Lee Royce!’ Cathy Shaw, owner of the Banyan Tree, a massage and therapeutic business in the town centre, tells me.

Cathy says she has ‘banned’ Royce from the Banyan. Rumour has it he is also barred from the Trades Club, Hebden’s renowned music venue.

We residents have been fielding calls and messages from friends all over the country telling us to look out for Royce, who is at large in the world of Happy Valley.

I’ve been asked if that was ‘my’ Nisa supermarket (it was), and did I just see your beautiful train station (you did) and where was that bicycle sequence by the reservoir shot? (Widdop, and it’s a lovely walk from town).

This is Hebden Bridge in the Calder Valley, my home for the past decade

Fans have also arrived in large numbers.

Local Labour party candidate Josh Fenton-Glynn says: ‘Cycling friends from London tested me about the route Tommy Lee Royce was on. Colleagues in Manchester ask for cafe recommendations.’

Taxi driver Naz Ali picked up a woman who lived in Liverpool — two hours away — who had come to see the real Hebden Bridge after watching the show.

‘Lots of people are coming now,’ he says. ‘Most of them don’t know where Hebden is. You can live in a different valley around the corner and not know where it is.’

This combination of celebrity and obscurity has long been part of the real Hebden Bridge, which has a story every bit as dark and bright as the television version.

The name comes from the Anglo-Saxon ‘Heopa Denu’, meaning bramble or wild-rose valley. Originally a tangle of marsh and briar where the river Calder met two becks, Colden Clough and Hebden Water, it was navigated and circumvented by pack-horse trails and bridges we still use.

In the 18th century, the area became notorious for an organised crime gang, the Cragg Vale Coiners. They were so successful that their coin-clipping — shaving off small pieces of coinage, then melting them down to mint counterfeit cash —threatened to destabilise the national currency.

Their ringleader, ‘King’ David Hartley, was hanged in 1774. Walking by his grave last week, we noticed people still scatter coins on it: a salute to a brigand who defied the Crown.

It is hard to imagine anyone but Tommy Lee Royce’s poor conflicted son Ryan (Rhys Connah), leaving anything on his grave, in the event Sally Wainwright sends him there. (Sunday’s climax is subject to much speculation, including rumours —denied by Connah — that multiple endings were filmed.)

It is a beautiful place wound around a confluence of moors and rivers — but it is a dark place, too, pounded by the weather, half-hidden from the sun in winter and carrying its own hard histories

Nina Oaken, a writer and artist, grew up in Happy Valley. ‘I feel the light and dark here in equal measure,’ she says. ‘The fiercely proud and independent thinking from the time of The Coiners onwards intrigues me. I do feel Sally Wainwright “boxed” many of the intrinsic contrasts, through observation of place and people.’

I had to ask what ‘boxed’ means in local slang: she said it means ‘captured exactly’.

‘During my teens, my closest friends were the children of the Hebden Bridge Hippies,’ Nina adds. ‘Their influence shaped a lot of the person I became. I have a visceral attachment to the landscape and architecture.’ The Hebden Hippy period came in the ’70s and ’80s.

The landscape, cheap rents and beautiful buildings climbing the hillsides drew creative and alternative types. They brought experiments in communal living, including one large and notorious squat.

Then came the drugs, turning Hebden into ‘a drug town with a tourist problem’, as the saying went.

Shed Your Tears And Walk Away, a tragic 2009 documentary by local director Jez Lewis, showed the consequences for a generation. ‘Why,’ Lewis asks in the film, ‘are the people I grew up with killing themselves?’ The answers included drugs, unemployment and divisions caused by gentrification.

Some of these dynamics are on stark display, of course, in Happy Valley. But, as ever in Hebden, there is a twist. The hippy phase also attracted people who wanted to live in a more caring and accepting town. The gay — especially the lesbian — community thrived.

Catherine (Sarah Lancashire), pictured, is Happy Valley’s battered and pithy heroine — often desperate, ever capable

Nina Oaken sees both sides of this legacy. ‘The hippy community brought the arts, innovative thinking and interesting characters living cheek-by-jowl with stoic farmers and a community trying to find a way out of post-industrial England,’ she says.

As for me, I struggle with the brutal winters and the shut-in claustrophobia they cast over the valley.

I find myself longing for Verona’s colour, its cypress trees, its food and sun. However, nowhere could be home to plainer-speaking or more supportive people than Hebden.

‘We don’t judge anyone here,’ a fellow parent said to me in the rain the other night, as we waited for our children. ‘People can live where they like, can’t they?’

With my posh voice and name I am often an outsider elsewhere, but they bother no one here.

This is a town where huge tractors thunder down the main street, where it is common to see women walking hand-in-hand, where eccentricity is welcomed and where people who have faced discrimination find sanctuary.

Happy Valley looks certain to bring more settlers, despite its portrayal of ex-heroin addicts, strugglers and strivers fighting to make a living and bring up children as best they can.

Amanda Dalton is a playwright and poet, a long-time resident who has caught her own version of the Happy Valley bug — not the action, but the observation.

We residents have been fielding calls and messages from friends all over the country telling us to look out for Tommy Lee Royce (pictured), who is at large in the world of Happy Valley

She describes a moment in Episode 3 of the current series when Catherine and Ryan (Tommy Lee’s son) are in the middle of an ‘awkward, deep conversation’.

As she puts it: ‘Catherine asks Ryan what he’s having for tea. “Stew” he says. “That’ll be reet,” she says. And she says it in just the right, throwaway way.’ Cathy Shaw of the Banyan Tree also finds Sally Wainwright’s ear for West Yorkshire dialect pitch-perfect.

‘My favourite line of last week’s episode was when Faisal’s wife was correcting their children’s grammar. First child: “He speeded past our house.” Mother: “Sped.” Second child: “Spud!”’

While the nation tunes into the quirks of local speech, and shudders at the thought of a dark valley stalked by small-time drug gangs, Hebden residents are enjoying the series in spite of its menace. Our home is being milked for its natural and social drama. The moors are not allowed to be too sunny on the screen, though they are great songs of space and light in fair weather.

The show layers them against stark estates in towns further along the valley.

‘Happy Valley’s direction hasn’t focused on whimsical Hebden Bridge,’ says Nina Oaken.

‘Outsiders may think it’s a place with Sowerby Bridge’s tower blocks and Pellon’s urban decay.’

This combination of celebrity and obscurity has long been part of the real Hebden Bridge, which has a story every bit as dark and bright as the television version. Pictured: Sarah Lancashire

It is this gothic version of the Calder Valley, in which conflict, damage and danger outweigh, but never quite overcome, tenderness and humour, that delights viewers here and far away.

Jill Jackson works behind the counter in Julie’s Fruit and Veg, the kind of greengrocer you remember as a child, glowing with fresh produce.

‘I love it! Most of all I love her —she’s so down to earth. She came into the cafe on the square every day. She was so friendly.

‘It doesn’t scare me! There are Tommy Lee Royces everywhere, aren’t there? I don’t find it dark. I find it very true to life, nowadays.’

Jill rolls the magnificent actor Sarah Lancashire and the fictional Tommy Lee Royce into one. What’s more, you can see and hear elements of Catherine’s blend of humour and dour fatalism in people throughout the area.

A few years ago, estate agent Garry Horsfield sold the property used in the TV show as Catherine’s house. He loves the drama and is delighted by the prospect of TV-inspired buyers.

But in the next breath he laments: ‘Our kids can’t afford to live here any more, can they? They’ve no chance against people from Manchester and London.’

Meanwhile, at our gorgeous train station, they are hanging on to a sign used in the filming, wondering whether they should erect it or sell it on eBay.

While light and dark are bound to wrestle on in the real Hebden Bridge, we are all hoping that right and justice will prevail in Sunday’s battle of elemental moral forces.

We are not sure we would trust our destinies to Sally Wainwright’s mighty pen. But as for our entertainment, in the dark mirror she holds up to us — bring it on.

She’ll be reet.

Source: Read Full Article