Written by Naomi May

As the fashion industry focuses more than ever on the diversification of its ecosystem, there are valid concerns that it’s leaving the north of England behind.

It was several years into her career that Siobhán O’Donnell first realised why she felt othered. “It took me a while to register it, but the minute I spoke, there was automatically a sense of, ‘OK, you’re from the north, so you’re almost definitely lacking something,’” O’Donnell says. “It seemed that I must have a lack of knowledge because I’m northern, and it was always as soon as I opened my mouth that eyebrows would be raised.”

The belief, O’Donnell observed, was that people suspected she could never hold a position as high as she does because of her thick Mancunian accent, and she herself felt that she had to be “better than average” in order to prove her worth. She adds: “I believe that when you start in the north, you have a lot of things you have to push through, and that is a life-long problem.”

Last week, O’Donnell, who’s spent her career working in fashion consultancy, launched the first-ever Northern Fashion Week in Manchester, which aimed to provide a platform for northern voices and figures in the industry. It was born out of the feeling that she had little to no opportunities and wanted to showcase the talent born from the north. The appetite for it has been clear among northern figures in the fashion industry.

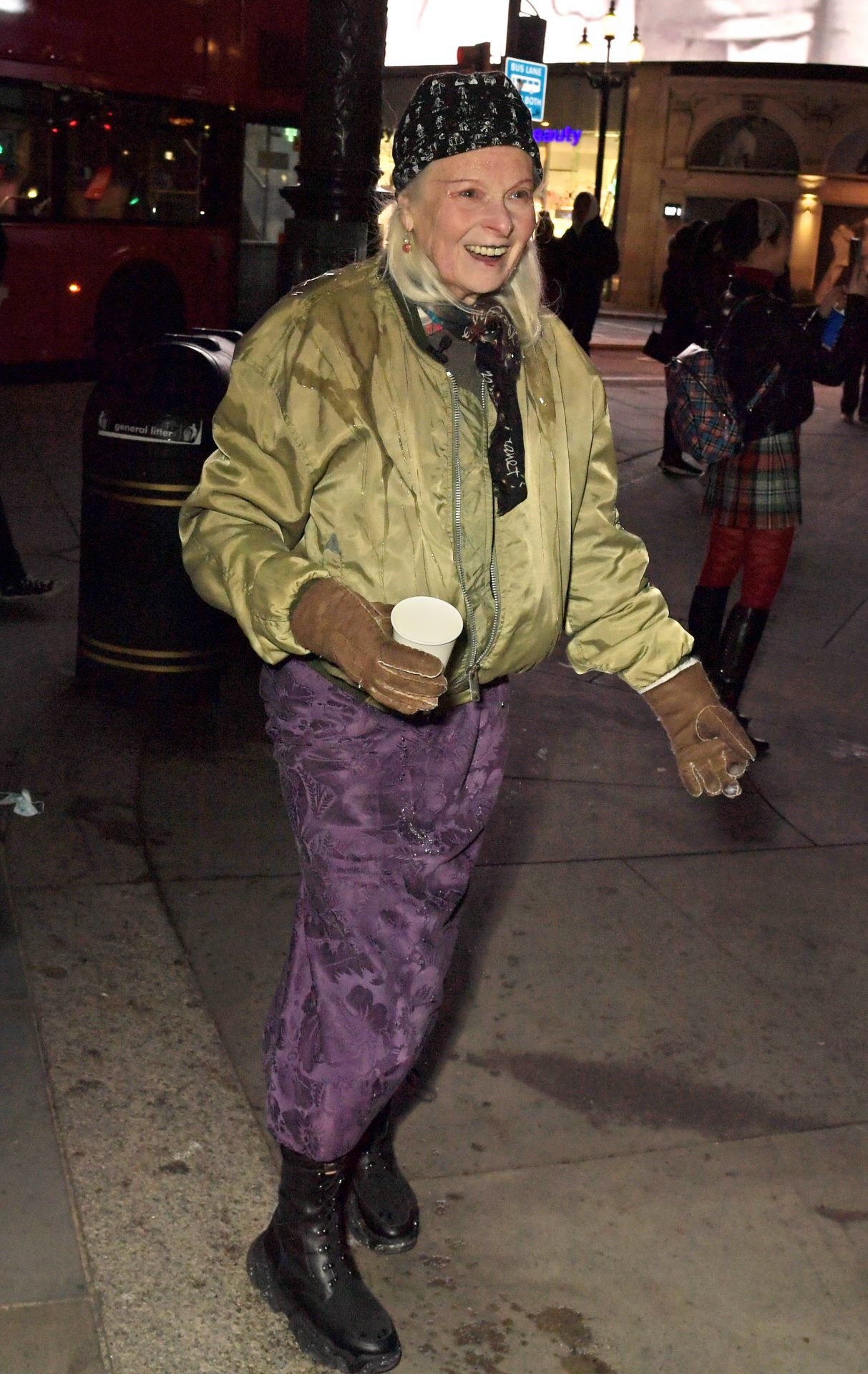

Nascent designers of recent years – most notably Patrick McDowell, Matty Bovan and Harry Styles’s favourite SS Daley – all hail from the north of England (as does the celebrated Vivienne Westwood), yet they are few and far between in an industry dominated by southern voices and perspectives. The criticisms that swarm around many creative industries, including fashion, is that its workforce and its problems are London-centric, which is to say that its blind spot is the north of England.

“It’s funny, I have always been told that I need to be in London in order to be successful, but I’m Manchester born-and-bred and it has just never felt properly right,” says L’Oréal Blackett, a host and writer. “It’s a double-edged sword having a thick northern accent in this world. On the one hand, people feel comfortable around you because it makes you become more amenable to people but on the other, I still find people make fun of my accent and that makes it difficult to be taken seriously.”

In July 2021, the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Textiles and Fashion released its Representation And Inclusion In The Fashion Industry report. Its findings were stark. 83% of subjects included in the study believed that the government should play a role in demanding better representation and inclusion in fashion, while the report itself concluded that there is a “lack of inclusion and representation in the industry” and that “sustained structural change is needed”.

The north’s fashion history is rich, too. In 1853, just 17 years before Manchester would gain the moniker ‘Cottonopolis’, the number of cotton mills in Manchester peaked at 108. As the industry changed with the creation and ascent of technology, so too did the north’s power position in the industry. It has become synonymous in recent years with the development of fast fashion; Missguided, I Saw It First, Pretty Little Thing and Boohoo all have headquarters based in Manchester, with many opting to make their collections in Leicester. According to recent statistics, the UK apparel market revenue will reach £60.17 billion in 2022.

This segregation of the British fashion industry, however, is only furthering the fissures between the north and the south. “The narrative of fast fashion being in the north and high fashion being in the south only makes the divide worse,” O’Donnell says. “It plays into the idea of the north being ‘cheap’. There are so many more barriers to brands being in the north that many northern designers choose to go down south.”

For Rochdale-born Lucy Maguire, who’s been trends editor at Vogue Business since 2019, it’s the unwritten code between northerners and southerners that has been the biggest barrier to navigating the fashion industry. “It’s so subtle, but just somebody’s proximity to London means their access to more opportunity, which I don’t even think people realised fully,” she explains. “It’s almost as though people from London can feel at home in the fashion industry there. They grew up around the restaurants and people that are in the industry; it feels comfortable to them. I didn’t know anybody that worked in fashion growing up.”

Maguire, like Blackett, has found that her accent has made people feel more comfortable gently mocking her or taking her less seriously. “If the fashion industry was less London-centric and more spread out, then northern voices wouldn’t be the exception.”

One such way to remedy the widening divide within the British fashion industry is to devolve the production or manufacturing of collections outside of London, in a way similar to the devolution of BBC services across the UK. O’Donnell agrees that creating more jobs and opportunities outside of London will help to heal the division. “It’s about education, it’s about investing in the fashion schools in the north and supporting the talent,” she says. “It’s also about making the north a desirable enough destination for brands to plant their roots here.”

“If fashion was moved around the country more, then there would be the opportunity to intern for free and to get their foot in the door properly in a way that means they can have cheaper rate or stay at home or commute from home,” Maguire adds. “Not everybody wants to leave their friends and communities that they’ve grown up in. Ultimately, if these aspects aren’t changed, then will they still want to work in fashion?”

Images: courtesy of Getty and writer

Source: Read Full Article