Brands are changing their strategies and entering policy debates, as climate change continues to upend the snowfall calendar.

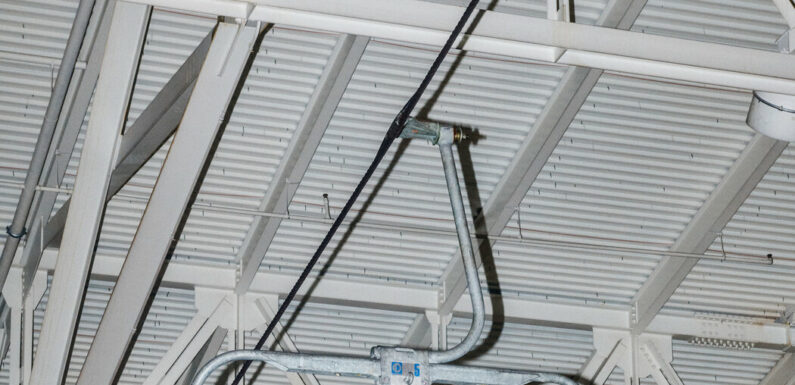

The chairlift at Big Snow, an indoor snow arena located inside the American Dream mall in East Rutherford, N.J., where “every day is a snow day,” according to the website.Credit…Jonah Rosenberg for The New York Times

Supported by

Send any friend a story

As a subscriber, you have 10 gift articles to give each month. Anyone can read what you share.

By Jasper Craven

On Feb. 1, 2021, during the biggest blizzard to hit New York City in five years, snowboarders turned city spots into their playground. Hollis DuPre, 23, grinded rails at 30 Rockefeller Plaza. Jayell White, a 30-year-old Bronx native, popped off a brick wall in Battery Park.

All of this was documented in the first film produced by Hell Gate, a scrappy snowboard crew. Last year, the crew’s second video, “Gate 2 Hell,” started on a far gloomier note. Trung Nguyen, 29, hiked up a mound of road salt. At the top, he dropped in and slid down the sodium chloride.

Cooper Winterson, a 28-year-old Hell Gate rider, said Mr. Nguyen’s trick “plays out as an ironic metaphor for what we’re dealing with. We don’t have enough snow to get clips, so we’re snowboarding on salt,” which, he pointed out, is used to combat snowstorms.

New York City is in a snow drought. Hell Gate’s members have had to travel instead to Buffalo, Albany and Poughkeepsie — or to Big Snow, billed America’s first and only indoor snow arena, at the American Dream mall in East Rutherford, N.J. The sealed slope ensures that, according to its website, “every day is a snow day.”

This message is cheerily reinforced by the mountain’s yeti mascot, who, on a recent Sunday, was seen twerking near the chair lift as house music played over echoey loudspeakers. Big Snow opened in 2019, and its everlasting winter has been repeatedly disrupted, first by the pandemic and then because of an electrical fire that broke out inside the 180,000-square-foot dome.

As climate change rewires the world’s weather patterns, skiers and snowboarders — along with the companies that outfit them — are pondering a future without snow.

“Our season is certainly shorter than it was in the past,” said Ali Kenney, 44, the chief strategy officer for Burton Snowboards. “Before, you could depend on a Thanksgiving and Christmas rush. Now, most of our activity is January to March.”

Over the coming decades, winter’s window is expected to shrink even more. One recent study led by researchers at the University of Waterloo warned that, by 2100, only one of the 21 previous Winter Olympics locations will have enough snow and ice to reliably host the Games. In response, many snow sports companies are diversifying. Salomon, once known for skis, has largely become an outfitter of running shoes, while Lib Tech, a snowboard manufacturer, now also makes surfboards.

Burton, the company that pioneered and popularized snowboarding, is viewed as the sport’s leader. It has nurtured the sport in important ways, including by helping bring snowboarding into the Olympics, and then supporting many Olympic snowboarders.

The company is now fighting to keep its cherished (and most profitable) season alive, but is also forced to hedge for the heat. Though it wants to save snowboarding, it also knows it needs to transcend it. Burton is attempting this tricky balance through a combination of environmental practices, promoting policies to protect winter, and efforts to diversify and expand snowboarding, which has long been dominated by a white and largely affluent ridership.

‘We Cannot Ignore It’

In 1977, Jake Burton Carpenter founded Burton out of his Vermont barn. Donna Carpenter now owns the company, taking it over after her husband’s death in 2019. In August of last year, Bloomberg reported that the private, family-owned company was exploring a sale, though Ms. Carpenter later denied it.

The Green Mountains in Vermont are far smaller than the peaks out west, but the state has been credited with popularizing snowboarding. In 1983, Stratton Mountain, in southern Vermont, became the first resort to welcome snowboarders, then developed training programs for them. The idea for the gravity-defying halfpipe — a long U-shaped feature, borrowed from skateboarding, that flings snowboarders high into the air — was developed in the state. Many of the sport’s top athletes were reared there, too.

Through the aughts, Vermont winters were reliably cold, and snowstorms were common. Each time 24 or more inches fell, Mr. Carpenter gave his employees in Burlington, Vt., the day off to hit the slopes.

Now a new form of winter is taking hold, one plagued by warm snaps and rain. A recent assessment from the University of Vermont warned that, by 2080, the state’s ski season could be shortened by a month. As good storms become less reliable, Burton has loosened its snow day rules, and now shuts down if a foot or more is projected.

“There’s a lot less energy around here when no one is feeling like they can get out and ride and experience the feeling that we are all seeking,” Ms. Kenney said. “The positive is that it increases the energy and commitment around our climate work. But it’s hard for it not to take a toll emotionally.”

The University of Vermont also studies snow’s shifting qualities. Kate Hale, a snow hydrologist at the university, said that light fluffy powder will become rarer as winters become more volatile. “Champagne powder requires consistently cold temperatures,” said Dr. Hale, 31.

Jeremy Jones, 48, a legendary backcountry rider, is torn up over a future without powder, which he described in almost spiritual terms. “It’s this weightless, effortless descent,” he said. “You’re barely connected to the earth.”

Mr. Jones carved his first turns at his childhood home on a board aptly named the Burton Backhill. Danny Davis, 34, a Burton rider and former Olympian, grew up on a Kmart board in his Michigan yard. Zeb Powell, a 23-year-old Burton pro, credits his mesmerizing bag of tricks to the Cataloochee Ski Area, a modest North Carolina mountain that, because of its limited features, forced him to be unconventional.

Low-altitude (and generally cheaper) slopes incubated talent and improvisation. This advanced the snowboarding’s countercultural flair, known as “steez,” a term popularized by the rapper Method Man that’s used to hail a snowboarder’s blend of style and ease. As snow migrates to ever higher elevations, accessible paths into the sport start to disappear, leaving only the biggest and most expensive resorts.

“I don’t know if today I’d be able to learn in my front yard,” Mr. Davis said. “The snow just doesn’t stick around Michigan like it used to.”

Much of the world is facing similar issues. Dachstein, a receding Austrian glacier where the 2022 Olympic gold medalist Anna Gasser honed her skills, closed for this entire season. Snowboarders see climate change up close, said Ms. Gasser, 31: “We cannot ignore it.”

In 2011, Ms. Kenney traveled across Europe and produced a troubling report on the future of the snowboarding industry there. She spent the next six months drafting plans for a sustainability program within Burton. She pitched them to Ms. Carpenter, who deputized her to overhaul company procedures.

Because Burton is family owned, Ms. Kenney said this work has been unencumbered by a “fiduciary duty to pursue profits at all costs,” adding that Burton’s efforts to become climate positive are costing millions in revenue each year.

Ms. Kenney is also mulling support for research on future snow patterns. These days, Burton makes conservative inventory estimates, then transports gear to places that have snow. This year, that’s been Japan and much of the American West, with even the temperate climate of Southern California experiencing rare blizzard conditions in and around the area.

At the same time, the East Coast and much of Europe is suffering. While Switzerland has been plagued by historically warm temperatures, Utah’s snowpack is 170 percent of the average, which, while generally appreciated, has also created avalanche risks and infrastructure headaches that have led to some temporary resort closures.

In 2013, Burton became the biggest financial backer to Protect Our Winters (POW), an advocacy group focused on climate policy founded by Mr. Jones in 2007. That same year, in a seemingly practical calculation, the company started its first spring/summer collection, which “captures the spirit of snowboarding in styles for hot days and long nights.”

In 2019, Burton became snowboarding’s first certified B corporation, a rigorous designation based on intense observation of company practices that followed years of work to balance profit, purpose and environmental accountability. It has introduced refurbishment and resale programs, and overhauled its supply chain with an eye toward sustainability.

With Burton’s blessing, riders, including Mr. Davis, have lobbied Capitol Hill lawmakers. Many are Republicans representing communities used to the cold and snow, including Representative John Curtis, Republican of Utah, a POW ally and founding member of the Conservative Climate Caucus who has used America’s bipartisan love of winter sports to push climate policies. Last year, he went hiking in his Utah district with POW athletes.

Mr. Davis said winter’s disappearance would “be so much more dire than sliding on snow,” invoking the specter of water shortages. “Snow is critical to humanity whether you like it or not.”

POW has also used its platform to call out those it sees as obstacles, including Jay Kemmerer, the owner of Jackson Hole Mountain Resort, who has adopted green resort practices — like renewable energy and water conservation habits — while also supporting politicians who deny climate change. Other snow resorts have also donated to climate-change deniers. (Earlier this month, 200 athletes signed a POW letter demanding that the International Ski and Snowboard Federation do far more to fight climate change.)

Ms. Kenney is also frustrated by some of Burton’s corporate peers. “Many companies are owned by private equity or a big holding company,” she said. “If snowboarding starts to decline, their reaction is, ‘Let’s just get out of that sport or sell that brand.’” (While snowboarders and skiers have long had a frosty relationship — largely because ski resorts long banned snowboarders from their terrain — Ms. Kenney praised Atomic, the world’s largest ski maker, which earlier this month announced a POW partnership, alongside efforts to adopt green company practices.)

At the same time, high-end fashion houses have ventured into the industry. Saint Laurent, Louis Vuitton and Dior are making luxe snowboards and outerwear for the sport. The U.S. Olympian Julia Marino won a silver medal at the 2022 Olympics on a Prada board. In 2016, Trevor Andrews, a Burton rider, was hired by Gucci to make his bootleg “GucciGhost” designs official. That same year, Burton collaborated with Jeff Koons to design a snowboard.

Tucker Zink is the general manager for Darkside Snowboards in Vermont, which operates three stores that have expanded to carry skateboarding and mountain biking gear. His store is now supplying more expensive options to attract high-fashion customers, many of whom flocked to resort towns during the pandemic. But in an attempt to protect snowboarding’s proletariat, Darkside has also built the “Dark Park,” located behind its Killington store, which offers day and nighttime riding, for free.

A Faint Smell of Plastic

Burton opened its first New York store in SoHo in 2005 on the corner of Spring and Mercer Streets. It featured a “cold room” where customers could test outerwear in frigid conditions. The store has since moved to a new outpost, on Greene Street. It may be the only place in the city where you can get a board waxed, and is a stop for OVRRIDE, a company that shuttles urbanites to the snowy north. It’s also an unofficial gathering place for the city’s snowboarding diaspora.

As Burton tries to branch out, the company has various programs to support new riders, with a particular focus on bringing Black snowboarders to the mountain. Selema Masekela, 51, a longtime X Games host and Burton board member, is helping lead these initiatives, which are informed by his decades of mistreatment on the mountain. “I got every sort of look and verbal thing thrown at me,” he said.

The late Virgil Abloh, an avid snowboarder, designed Burton collections in 2018 and 2022. These lines fueled the company’s efforts to introduce the sport to people of color, most notably through the Chill program, which says it has introduced the sport to thousands of people, chiefly by subsidizing the costs to get up on the slopes and learn.

One of those athletes is Brolin Mawejji, 30, who started snowboarding as a boy after landing in Massachusetts as a Ugandan refugee. In 2022, he became the first snowboarder to represent his country in the Winter Olympics. He said that amid the trauma and instability of his childhood, “snowboarding gave me inner peace.”

On a drizzly evening earlier this month, Burton’s SoHo store hosted a party for its new collaboration with the rap group Run DMC. The collection was spearheaded by T.J. and Jesse Mizell, two sons of Jam Master Jay, the group’s D.J., who was fatally shot in 2002.

The Mizells said they hoped their line would encourage more Black people to get into snowboarding, or at least borrow the sport’s style. “We want to see people walking through SoHo in Burton being like, ‘I’ve never ridden a snowboard before, but this tech is insane,” said T.J. Mizell, 31.

Perhaps the most hyped-up rider at the event was LJ Henriquez, a 14-year-old prodigy from New Jersey who largely built his skills at Big Snow’s mall hill, which is more accessible than most mountains, relatively cheap and offers eerily consistent conditions. The short and narrow slope is dotted with fake Christmas trees and illuminated by harsh fluorescent flood lighting. It’s stocked with rows of industrial-grade air-conditioners and has a faint smell of plastic.

“You’re missing the birds and the trees and the sun, which is weird,” said Brian Burke, a 31-year-old from Maine, who waited in the Big Snow line while a cheerleading competition wrapped up in the atrium below. The pro snowboarder Mr. Powell, after his own recent visit, leaned into Big Snow’s bizarre locale by snowboarding down a mall escalator.

There’s also a clear difference between feathery natural snow and its fabricated form. Each real crystal is beautiful and unique, while the fabricated stuff is akin to chopped ice. (Ms. Hale, the winter researcher, said the natural flake — known scientifically as the stellar dendrite — cannot be replicated by a snow gun.)

On a recent weekend, there was an eclectic mix of skiers and riders at Big Snow, along with many mall-goers who stared at the mountain through big windows, seemingly astonished at the sight of a substance that has barely fallen all year.

Site Index

Site Information Navigation

Source: Read Full Article