The question at the heart of “Ain’t No Mo’,” the incendiary and incisive new comedy that opened on Broadway on Dec. 1, is riotously and fruitfully absurd. Consider it a gleeful reframing of a racist taunt: Black people have long been told to “go back to Africa” by those whose assimilation into whiteness has blinded them with delusions of America’s purity. Well, what if that was actually the plan? If hightailing it out of here would be preferable to putting up with white supremacy and its violent consequences for even one more day?

Written by and starring Jordan E. Cooper (BET’s “The Ms. Pat Show”), “Ain’t No Mo’” wrangles rhetorical fantasy into a rolicking, high-concept sitcom, mining dark comedy from the horrors of racism and the particulars of Black life. Explosive as a hand grenade of laughing gas, it’s heady and hysterical and fearlessly provocative. Its keen observations about race as both social construction and lived reality crackle like a lit fuse. With a dynamite cast of six taking on a dizzying array of characters, “Ain’t No Mo’,” produced on Broadway by a team led by Lee Daniels, is a daring and uproarious feat of performance that is thrillingly alive to the moment.

That includes recent history, in the monumental ascension of a Black man to the White House and the sea change it was naive to assume would follow. “Ain’t No Mo’” opens on a funeral in a Black church, where women in elaborate hats make a pageant of their grief and an impassioned pastor (Merchánt Davis) riles up the audience. The deceased is purely metaphorical — the right for Black people to complain, laid to rest along with America’s blood-stained past on Election Day in 2008. Laughable, yes, but in the deeply sardonic, resigned way that one looks atrocities in the face and can muster no other response.

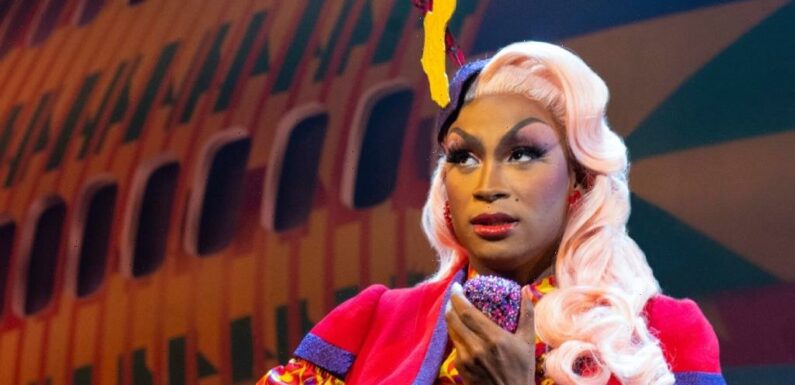

That’s an apt way to describe the divinely made-up visage of Peaches, the flight attendant played by Cooper, who, in the next scene, reveals the play’s overarching conceit in an efficient, if facile, expositional phone call (the man on the other end better haul ass to the airport before he gets left behind). The last flight out on African American Airlines is departing from gate 1619, and there’s room for every Black person on board. Anyone who looks back or chooses to stay will be transmogrified into a white man, losing their soul and ability to empathize. Limited room may open up for Latinos on standby.

The ensuing series of vignettes unfolds with the free-wheeling verve of ‘90s sketch comedy show “In Living Color” and engages in direct conversation with George C. Wolfe’s 1986 play “The Colored Museum,” similarly structured as a revue-style survey that toys with stereotypes and preoccupations of Black life. A grieving woman (Fedna Jacquet), one among millions in line to get an abortion, doesn’t want her unborn child to meet the same fate as her murdered lover. A reality show taping that stars “real baby mamas of the south side” sends up race as a performance of signifiers, including by a cast member (Shannon Matesky) who claims to be “transracial” in the style of Rachel Dolezal. A stand-off between her and the other women erupts in a way the cameras are designed to devour.

Nearly every scene threatens to spin out of control, generating unbridled momentum and almost dissolving into chaos before the play’s organizing principle reins in the action. The strategy works both structurally and metaphorically, putting a finer point on the play’s premise: This country is a mess and it’s time to get the hell out. Consistent as that throughline is, “Ain’t No Mo’” is also a minefield of surprises, totally unpredictable from one minute to the next.

In some ways “Ain’t No Mo’” is impossibly overstuffed, like the cabin of a plane meant to reverse centuries of diaspora. Cooper’s artistic investigation is ambitious, raising a lot of questions that it’s smartly selective about addressing. Rather than dwell on what sort of life would await Black Americans in Africa, Cooper positions the continent as a utopian shorthand, however inconceivable, for a fresh start. He is more keen to lay bare, with vicious precision and biting wit, the conditions that make any manner of escape seem desirable. That he manages to make comedy his sharpest tool is a testament to his dynamic skill as a writer.

Cooper is also a charismatic and commanding onstage host, in the drag tradition of a queen who takes no shit — in a performance all the more impressive for being done solo, with imaginary scene partners in unseen passengers and powers that be. Peaches’ queerness allows Cooper to point to the narrow ideas of Black masculinity imposed from within the community, another complication among many in this so-called trip to paradise.

The ensemble includes particularly remarkable performances from Ebony Marshall-Oliver, also a highlight of last season’s “Chicken & Biscuits,” and Crystal Lucas-Perry, who led this fall’s revival “1776.” Under the direction of Stevie Walker-Webb, who returns, along with most of the cast, from the play’s 2019 premiere at the Public Theater, the actors demonstrate astounding versatility and commitment to characters largely defined by their symbolic weight rather than individual personality. Hair and wig design by Mia M. Neal and costumes by Emilio Sosa both do extraordinary work visualizing each one.

Of course, Black culture is intractable from — and essential to — American culture, and suggesting they could ever be separated is a fallacy, an idea represented here in perhaps the least successful of the play’s theatrical devices (a cosmically flashy piece of carry-on luggage). So what is to be done? “Ain’t No Mo’” does not propose that the answer is to run away, despite elaborately imagining just that. Rather, it argues for the need to recognize the mess our country has wrought — and at whose expense — without flinching or turning away because it’s too much to bear and realizing that many people have never had that luxury. There is no other way to get off the ground.

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article