“There is no meaning to life apart from the movie story,” writes Joyce Carol Oates in the opening pages of “Blonde,” “and there is no movie story apart from the darkened movie theater.” If it was inevitable that Oates’ novel about Marilyn Monroe would be made into a movie, it’s also a little ironic that that movie was made by Netflix — suffice to say that few who see “Blonde” will do so in a darkened movie theater. How many potential viewers are scared off by its runtime of 167 minutes is impossible to say, but there is a good reason for its protracted length: The book is similarly imposing at 738 pages. A finalist for both the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award, Blonde was released in 2000 and adapted once before — not that the CBS miniseries starring Poppy Montgomery garnered nearly as much attention as this new version has.

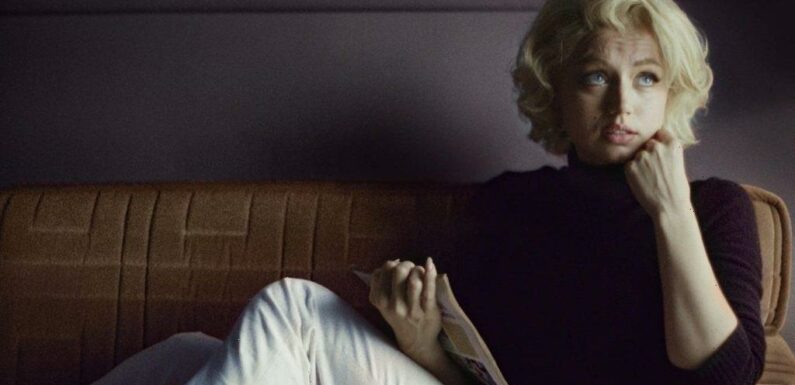

Directed by Andrew Dominik and starring Ana de Armas as Monroe (née Norma Jeane Baker), “Blonde” is one of those movies that generates headlines, elicits controversy and inspires hot takes long before anyone has seen a single frame. How could it not? Marilyn Monroe is one of the 20th century’s most enduring icons, one who’s been engendering strong opinions for the better part of a century, and like other tragic figures — including one of her reported lovers — her untimely death only made her more famous.

Talking Fetus? Yes or No?

If you’re wondering how faithful Dominik is to Oates’ novel, the answer is somewhere between “quite” and “very.” If you’re wondering whether the book also features a talking fetus, the answer is no. Yes, you read that right — there are indeed several scenes in which Monroe talks to her unborn child and the CGI fetus talks back, one of many apparent attempts at intimacy that instead feel ghoulish (not least because the fetus at one point asks “Why did you kill me last time?”)

Runtime and talking fetuses notwithstanding, the film is in some ways more accessible than its source material. Oates’ book is heady, often willfully and self-consciously so. Most of it is narrated from the third-person omniscient perspective, while some passages read as though they’re coming from Monroe herself and others are told by unnamed members of the production crew on her various films. (One such passage: “Oh yes certainly we’d hated Monroe at the time we knew her but afterward seeing the movie we adored her.”) None of this is ever clearly delineated, and it rarely seems worth the effort to try and game out exactly whose perspective we’re getting — Oates works so hard to keep us on our toes that trying to orient ourselves would almost be to ruin the trick.

The Pseudonyms and Initials

Then there are the pseudonyms. Whether for legal reasons or simple creative license, few of the celebrities mentioned in the book are referred to by their real names. Monroe’s three husbands — James Dougherty, Joe DiMaggio and Arthur Miller — are called Bucky Glazer, The Ex-Athlete and The Playwright, respectively, while actors and studio executives usually go by a single letter. Tony Curtis is C, Billy Wilder is W and so on and so forth. These can be a bit much at times, especially when bunched together as they are in this passage relating to Monroe’s efforts to be cast in 1952’s “Don’t Bother to Knock”: “W had the right to choose his co-stars. Norma Jeane would hear from the producer D, if W liked her OK. He’d pass her on to D in that case. Or maybe not? Of course there was the director N, but he was in the hire of D, so possibly N wouldn’t be a factor. There was the studio executive B. What you heard of B made you wish not to hear more.”

Fewer Daddy Issues

The movie eschews these pseudonyms aside from the credits, opting instead to have key characters go nameless — spare a thought for anyone who doesn’t already know about Monroe’s marriages, as they’ll have only a vague sense of who Bobby Cannavale and Adrien Brody are playing. (Not even the end credits reveal them as DiMaggio and Miller.) One improvement the film does make: Marilyn refers to these significant others as “Daddy” slightly less often than she does in the book, which might come as a surprise considering how often it happens in the film. It’s near-constant in the novel, to the point where you can’t help wishing Oates would stop hammering home this aspect of Monroe’s relationships and move on to another point; a search of the Kindle version turns up 170 instances of “daddy,” the vast majority of which are in the same context as lines like page 593’s “Ohhh, Daddy. You’re m-mad at me?”

Norma Jeane vs. Marilyn

Dominik also makes less of a distinction between Norma Jeane and Marilyn, whom Oates almost treats as distinct entities. Oates usually refers to the actual person as Norma Jeane, while everything from “Marilyn Monroe” in quotation marks to the Blond (not blonde, for whatever reason) Actress to MARILYN MONROE is used when referring to her dealings with others, indicating that she was playing a role even when she wasn’t filming a movie. (“Marilyn Monroe’ is this foam-rubber sex doll I’m supposed to be, they want to use her until she wears out; then they’ll toss her in the trash.”)

Marilyn’s Teen Years

Oates also devotes far more time to Norma Jeane’s formative years, especially the orphanage and foster home where she spent several years, and doesn’t play with time as the movie does. Dominik cuts straight from her arrival at the orphanage to the beginning of her acting career, eliding her time in foster care, her first marriage at just 16 years old and the adoption of her stage name, among other important life events. Time constraints are what they are, especially when a movie is already nearing three hours, but this context added much to the novel that’s missing in the adaptation.

The longer “Blonde” goes on, the more another recent film about a talented, beautiful actress whose life ended tragically comes to mind: “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.” Sharon Tate was no less a victim than Marilyn Monroe, and yet Quentin Tarantino chose not to portray her that way. Instead he showed her full of life and joy as she sneaks into a movie theater to see her own movie, glancing at the audience who doesn’t recognize her and smiling every time they laugh. Tarantino played with history to achieve his happy ending, to be sure, but neither Oates nor Dominik were shy about that — they just went the opposite direction with it. To wit, both depict the untimely death of Monroe’s former lover Charlie Chaplin Jr. as a traumatic event immediately preceding her own death despite the fact that he died six years after she did.

The filmmakers’ intentions in depicting Monroe as a victim several times over may well have been noble, but in doing so, the movie — taking a cue from Oates’ novel, it must be said — often infantilizes her and removes her agency. Neither book nor film features a single scene of Monroe absolutely nailing a scene and smiling about it afterward, and the fact that she won a Golden Globe for “Some Like It Hot” is never mentioned either. (The novel even goes out of its way to erroneously claim that she “never received any award for her acting in the United States.”)

Double Downer

Of course Marilyn Monroe was treated harshly by Hollywood, the public and the world. But in focusing exclusively on the most miserable aspects of her life, Dominik is doing the same thing he’s supposedly criticizing. Monroe was a victim, but she was also so much more — that Golden Globe was richly deserved, and she was just as magnetic in everything from “Niagara” to “Monkey Business,” where she stole every scene she was in. If the artists portraying her aren’t interested in the full spectrum of her life, perhaps they shouldn’t portray her at all.

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article