Charm, a sadly rare theatrical quality, is scarcely a fashionable theatrical virtue, but it’s nonetheless valuable. And, to audiences’ evident delight, it’s there in spades in director Daniel Evans’ wonderfully fluid farewell production at Chichester Festival Theatre. Turning Bill Forsyth’s 1983 Scottish eco-comedy-drama “Local Hero” into a musical, Evans and every member of his first-rate production team create an often-idiosyncratic delight, the stage equivalent of one of British cinema’s tender-hearted, quirky-yet-cosy Ealing comedies. What even he cannot give the show is true theatrical liftoff.

An earlier version, directed by John Crowley, played Edinburgh to pleasing reviews in 2018. Crowley left the project during the pandemic and Evans took over, keeping no one but Scots playwright David Greig, the music and lyrics of Mark Knopfler (formerly of Dire Straits), and lighting designer Paule Constable.

Although there have been trims to the original film’s plotting, plus rewrites, the basic material remains largely the same. The story of an American who arrives in a remote Scottish village and unexpectedly falls for its varied delights is hardly original — Lerner & Loewe got there as far back as 1947 with “Brigadoon.” But this story has more politics since the central character of Mac (Gabriel Ebert) is a Texas oil company representative sent to the fictional village of Ferness to purchase not just a parcel of land. His company is intent on building a giant petrochemical oil refinery, and he’s going to buy the entire village and its coastline.

Under orders from his gazillionaire boss (Jay Villiers), Mac leaves his state-of-the-Eighties, gray-is-good Houston office after Sasha Milavic Davies’ snappily choreographed opening number “A Barrel of Oil” (the nearest the show gets to traditional musical theater), and sets off for Ferness. He stays at the local pub run by Gordon (wholly engaging, wonderfully easeful Paul Higgins) who is also the town solicitor, and Stella (Lillie Flynn) who is both the chef and the free-est spirit around.

But while Mac is gradually seduced by the place and its values that make him reconsider his own life, the surprise of the story is that instead of being about a community up in arms about the desecration of the natural world, the locals are quick to spot potential. Others may see the place as one of natural beauty, but to them it’s just their downtrodden, stuck-in-the-past home in which everyone struggles to make ends meet. Mac is going to save them. As the bouncy ensemble song puts it, they’re going to be “Filthy, Dirty, Rich.”

Knopler wrote the original’s atmospheric score and for the musical he and orchestrator Dave Milligan again use its Celtic sound — the instrumentation runs to fiddle, accordion and double-bass alongside Knopfler’s more expected soft-rock electric and acoustic guitars. Musically, he has a nice way with yearning ballads, especially those hauntingly sung by Lillie Flynn and the quietly assured Jackie Morrison, but his lyrics are either generic or strained. The jig-like song “Big Mac and Gordon,” about the sale agreement they reach, is suitably folky and jaunty, but elsewhere too many numbers amble and ramble rather than achieve dramatic momentum — so much so that although the songs have the aforementioned charm, their overall effect is sweet but anodyne. You keep waiting for the song that really raises the temperature, but one never comes.

Grieg’s warmly witty book, mined for every detail by Evans’ immensely characterful cast, offers more to play with than many a contemporary musical (a vast improvement on his “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory”), but the downside is that instead of further developing the story, Knopfler’s songs feel like illustration. The effect is often of a play interrupted.

Gentle-voiced Ebert is winningly fish-out-of-water as Mac and makes his transition entirely plausible, while Hilton McRae adds a nice dry tone to fanciful, beachcombing Ben who finds himself as the story pivot.

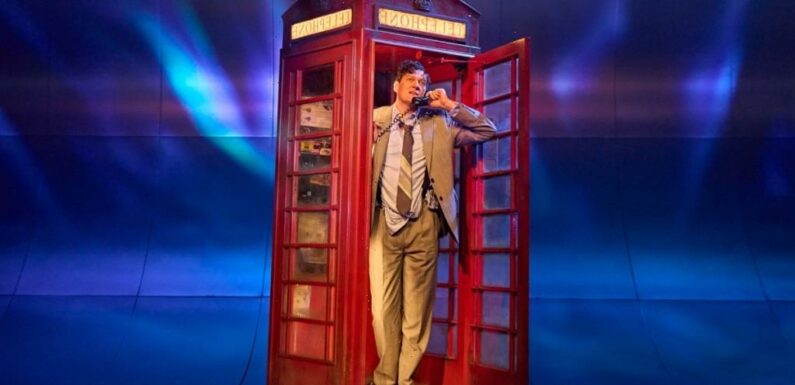

Much of the production’s success is down to the show’s look. Aside from the holdover of the red phone box, central to the pre-cellphone 1980s story, the design team avoid the literal, which makes sense since they are robbed of the film’s cinematography of the landscape. Instead, they cleverly allow the audience to use their imagination. Frankie Bradshaw’s cunning, counterintuitively simple steel wave of a set accepts Constable’s color-saturated lighting and Adam J Woodward’s video to conjure sea, sky and even the Northern Lights. Against that, Evans guides the show with a carefully controlled yet almost homespun aesthetic. Rather than showing off its versatility, it reflects the mood of the character’s lives.

There’s a sweetness to the show that is sometimes whimsical but undeniably appealing. And, for the most part, it evokes sentiment rather than trading in sentimentality. It’s just a shame that the songs only occasionally enrich it, and more often shortchange it.

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article