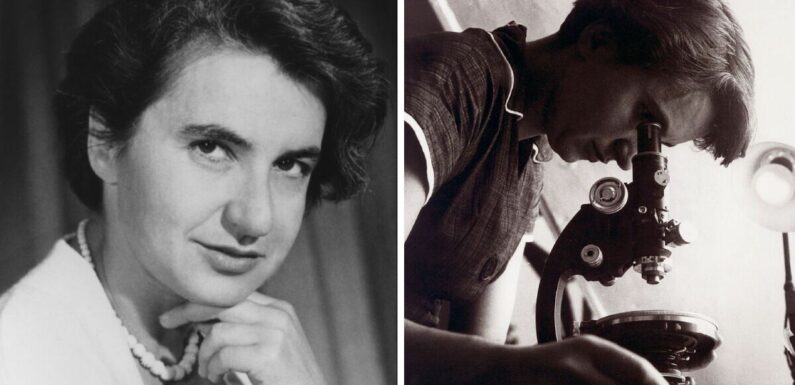

Brilliant female scientist Rosalind Franklin was an “equal contributor” to the discovery of DNA but was airbrushed out of the historic breakthrough due to sexism, a 70-year-old news article has confirmed. The unpublished and overlooked feature and letter, both written in 1953, add to other evidence that she was key to defining DNA’s structure – which would transform medical – and criminal – investigations.

Despite her role, she was handed a raw deal – failing to receive due recognition and praise for her work in the seminal paper by colleagues James Watson and Francis Crick.

Many believe the eureka moment – the discovery of the “double helix” which pinpoints our genetic code – came when Mr Watson was shown an X-ray of DNA taken by Ms Franklin.

It was used without her permission or knowledge, amid claims she failed to understand its significance.

But documents show that Ms Franklin was fully cognizant of it and party to its discovery.

Matthew Cobb of Manchester University and Nathaniel Comfort from the John Hopkins University School of Medicine have made a case in support of her.

In a comment piece in this week’s Nature they argue that Ms Franklin was “an equal member of a quartet who solved the double helix”.

Yet Ms Franklin was a victim of sexism, receiving disparaging remarks from co-workers who disliked her businesslike “abrupt” nature.

She was branded the “dark Lady of DNA” by her biographer Brenda Maddox in reference to the misogyny.

This negative appellation undermined the positive impact of her discovery and left the London-born scientist in the shadows of one of history’s biggest ever breakthroughs.

But Professor Cobb and Professor Comfort state that – along with Maurice Wilkins – Ms Franklin was “one half of the team that articulated the scientific question [about DNA], took important early steps towards a solution, provided crucial data and verified the result”.

Known as Photograph 51, the image of the double helix is treated as “the philosopher’s stone of molecular biology”, write the profs.

They explain: “It has become the emblem of both Franklin’s achievement and her mistreatment.”

In the historic version of events Ms Franklin is portrayed as a brilliant scientist, but one who was ultimately unable to decipher what her own data were telling her about DNA.

She reportedly sat on the image for months without realising its significance, only for Mr Watson to understand it “at a glance”. But while visiting Ms Franklin’s archive at Churchill College, Cambridge, the authors unearthed a hitherto unstudied draft news article. It was written by journalist Joan Bruce in consultation with Ms Franklin, who was to die aged just 37 from ovarian cancer.

It was meant for publication in Time magazine. The scientist duo also found an overlooked letter from one of Ms Franklin’s colleagues to Mr Crick. They believe this confirms her crucial role in the breakthrough.

Prof Cobb and Prof Comfort write: “She was up against not just the routine sexism of the day, but also more subtle forms embedded in science – some of which are still present today.”

They conclude: “She deserves to be remembered not as the victim of the double helix, but as an equal contributor to the solution of the structure.”

Source: Read Full Article