Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

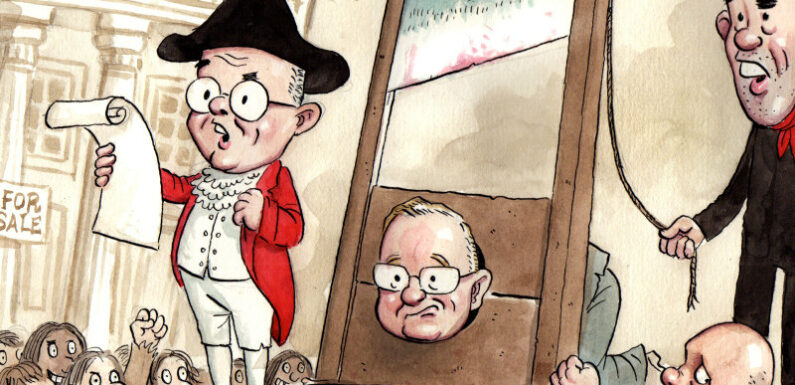

Friday was Bastille Day, the perfect day for a political execution. The Reserve Bank governor, Philip Lowe, was put to the guillotine, the perfect scapegoat for a government anxious about the economic future.

By the time his term expires on September 18, Lowe will have completed, or all but completed, the dirty work that no politician would ever want to do. He took away the free money.

Illustration: John ShakespeareCredit:

This was his economic responsibility, and his political crime. This was what made him a serious central banker, and the reason he has been decapitated.

Lowe made mistakes in his seven years as chief of the central bank. No question. His main blunder was to suggest that interest rates would most likely stay fixed near zero until 2024. Many thousands of people borrowed money on the strength of this statement and now face unmanageable repayment burdens.

But in his core job, he did exactly what he was supposed to do – raise interest rates to bring inflation in check while doing the least possible damage to employment.

“He did no worse than any other central bank, and some got it worse,” says Warwick McKibbin, an eminent expert who has the rare qualifications of having served as not only a staff economist for the Reserve Bank but later as a member of its board.

This left the government in a tricky spot. Lowe’s Reserve Bank has been successful and the government is happy to take the credit. Albanese on Friday told reporters to consider the “global economy with rising inflation, rising interest rates right around the world”.

“There is nowhere where you’d rather be than this great country of Australia,” bloviated the prime minister. “We have the best employment growth, we have inflation which is better than that of our competitors. We have interest rates that are lower than they are in the UK, in Europe, in North America.”

So Australia’s situation is about as good as it gets, and Phil Lowe’s central bank, more than anyone else, is responsible. Yet despite signalling repeatedly that he’d like a three-year extension to his term, he’s being terminated.

Asked directly by a reporter why Lowe was not allowed an extension, Treasurer Jim Chalmers didn’t give an explanation. He merely said he believed Lowe’s deputy, Michele Bullock, to be “the best person to take the bank into the future”, offering “a fresh leadership perspective”. At the same time, Albanese and Chalmers lavished praise on Lowe. Chalmers told a press conference: “Phil Lowe goes with our respect, he goes with our gratitude, and he goes with dignity.”

Albanese told the same press conference: “Can I make this point as well, with regard to the public service, one of the things I want my government to be characterised by is lifting up the respect for the public service, which is an honourable profession.”

In other words, the government claims credit for Lowe’s policy even as it fires its architect. The government praises Lowe even as it buries him. And the prime minister wants to lift respect for public servants even as he dumps a successful one. And neither can explain the contradictions.

Because the truth is one they won’t speak. “They’re just happy to have Phil as a scapegoat,” says a former senior Reserve Bank official who didn’t want to be identified.

In a peculiar juxtaposition, a royal commissioner last week lashed senior public servants for failing to stand up against political pressures. That was over the robo-debt scandal. This week, a government replaced a senior public servant for standing up against political pressures. Lowe was frank and fearless. Now he’s to be unemployed.

He’s been described as Australia’s most unpopular person, which might be true. While he was raising rates, politicians queued up to rant against him for kicking the Australian people in the guts. While the British government, for instance, defended the Bank of England governor for doing the same, the Albanese government was happy to leave Lowe exposed to public and political anger. And the government sometimes joined the queue of accusers.

Last month, Chalmers responded to the latest rate rise by distancing the government from it, and directing the public’s ire to Martin Place, saying, “A lot of Australians … will find this decision difficult to understand and difficult to cop.”

When a government economic forecast proved wrong, Albanese excused himself by pointing to Lowe’s forecasting failure. “That’s not the only prediction on interest rates that have not been correct,” the prime minister said of the government error. “It’s not as incorrect as the one saying there’d be no increases till 2024. So these things are all relative.”

Lowe won’t get much sympathy and he doesn’t expect it. Paid $1 million a year and feted as a deity in the finance world, he’s not going to be destitute. His immediate priority, he’s told colleagues, is to get his golf handicap into the single digits. Besides, one day he’ll be able to rediscover the simple pleasures of going out with his family, a luxury denied him in his status as scapegoat.

So he’s a handy villain. He exits the stage and takes with him the blame for all – or almost all – the interest rate increases while Albanese gets to boast about Australia’s relative economic success. It’s a jarring move for a prime minister who says he wants more respect for the public service. And it’s a case study in Albanese’s capacity for ruthlessly pragmatic politics when he sees advantage.

But hold on. What about the reforms to the Reserve Bank that were recommended by a three-person expert panel? Chalmers says Michele Bullock is the best person to implement the reforms which, he says, he’s discussed with her extensively. Fair enough. You might well want a new leader to implement change. This is Chalmers’ best argument for replacing Lowe. But don’t expect any substantive change to the Reserve Bank’s core function.

Yes, the review proposes fewer meetings of the Reserve Bank board, more press conferences, and a second board, stacked with monetary experts, deciding interest rates.

Yet the review doesn’t propose any serious change to the central bank’s objectives nor its mechanism for pursuing them – the “big stick” of interest rates. So if your gripe against the bank is the way it’s raised interest rates, don’t expect anything significantly different from the new regime.

McKibbin says that, if Lowe erred, it was in waiting too long to start raising rates. McKibbin gives credit to the Reserve Bank of New Zealand for seeing inflation earlier and acting sooner.

But it was a matter of months and, other than NZ, “all central banks made similar mistakes”, says McKibbin, distinguished professor of economics and public policy at ANU’s Crawford School. Lowe’s main misfortune, McKibbin says, was to have his seven-year fixed term expiring just as public and political criticism reached a crescendo.

In the larger scheme, Lowe’s experience is a textbook illustration of why central banks were given independence to begin with, a modern phenomenon that took hold mostly in the 1990s and, in Australia’s case, it was formalised by the Howard government’s treasurer, Peter Costello, in 1996.

Want to see the counterfactual? Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan approached his re-election effort this year with the staccato sacking of three central bank governors who all wanted to raise interest rates. Erdogan, fearing a downturn during an election campaign, demanded that rates stay low.

The moment Erdogan was re-elected, he appointed a serious central banker who immediately nearly doubled official interest rates from 8.5 per cent to 15 in a single swoop. But by that point, Turkey’s inflation rate had reached 40 per cent on the official measure and more than 100 per cent in reality. The result? The Turkish people face the worst of both worlds – outrageous price increases followed by a sharp economic downturn, shocking inflation followed by avoidable recession. Politicians simply can’t be trusted to do the unpopular but necessary work of raising rates.

So the system in Australia broadly worked as intended. But this won’t be much consolation for Albanese as he heads to the next election. The fate of the Voice referendum, win or lose, will be a lesser concern than the state of the economy.

He wants to be able to go to the people with low inflation, strong employment and falling interest rates. If he gets this Goldilocks outcome, it’ll be in large part thanks to the dirty work done by Lowe’s Reserve Bank. If he doesn’t, he’ll blame the late Lowe, executed for crimes against popularity. Vive la revolution!

Peter Hartcher is political editor.

The Opinion newsletter is a weekly wrap of views that will challenge, champion and inform your own. Sign up to receive it here.

Most Viewed in Politics

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article