Ever since Rebel Wilson announced the birth of her first child this week via a surrogate, people have wondered: what is commercial surrogacy? How much does it cost? And why can’t we do it here?

“Thank you for helping me start my own family, it’s an amazing gift,” said Wilson of the “gorgeous surrogate” who carried and birthed her daughter, Royce Lillian. It was, the Australian actor added, “The best gift!!”

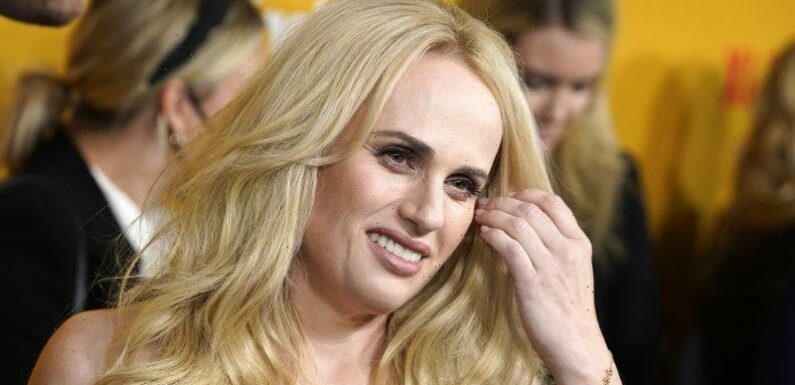

“So I’d lost a huge amount of weight and been through three surgeries at that point and no viable embryos,” Rebel Wilson, who just welcomed her first child via a surrogate, said recently, about trying for a baby. “It was devastating.”Credit:Invision

Surrogacy has long been a popular choice among celebrities, with Kim Kardhashian and Khloe Kardhashian, Cameron Diaz, and Priyanka Chopra among those who have welcomed children via other women who have carried and birthed their child. Wilson, 42, recently said she had been “devastated” by the news her fertility treatments were unsuccessful, and that the result of three surgeries was “no viable embryos”.

It’s not known whether any of these celebrities welcomed their children via commercial surrogacy or altruistic surrogacy. With the former, another woman carries and births another couple’s child and is compensated for her services, above and beyond her medical expenses. With the latter, another woman births and carries another’s child, but is only compensated for her medical expenses.

Only altruistic surrogacy is legal in Australia. Precisely because commercial surrogacy is, in its strictest terms, not a gift.

“We don’t allow people to buy and sell any bodily tissues in Australia,” says Dr Evie Kendal, a bioethicist and public health researcher at the Swinburne University of Technology. This includes sperm, blood, eggs, organs. It’s illegal in Australia to sell or pay for these.

“We don’t want trafficking in human body parts or reproductive material. And sometimes commercial surrogacy is compared to [human] trafficking,” says Kendal, noting that babies born via commercial surrogacy are born in foreign countries, and then brought back to Australia.

In many cases, she adds, women who become surrogates are from disadvantaged, rural communities, and they experience bad conditions. “Some people describe it as surrogacy farms,” says Kendal, referring to hospitals where groups of women are sometimes taken and held throughout their pregnancies. “Because they sign contracts that agree to these rather demanding terms, because the couple will want a specific diet, no smoking, no drinking and exercise.”

It’s these issues, she says, that are at the heart of Australia’s surrogacy legislation.

“Essentially, [the reasoning is] there are certain things that shouldn’t be on the market as commodities,” says Kendal. “So, we shouldn’t be buying children, essentially. But people engaged in commercial surrogacy wouldn’t describe their behaviour that way.”

Conservatism and prejudice are also at play, says Sarah Jefford, a lawyer specialising in surrogacy and donor conception in Melbourne.

“Often, when there’s a debate around surrogacy [here], it’s ‘two dads shouldn’t have a baby,’” says Jefford, noting that Australian gay men have often used surrogates overseas as it has traditionally been harder for gay men to access IVF or surrogates here. (In Western Australia, gay men and single men are prohibited from accessing IVF, because people must have a “medical reason”, like having no uterus, or having fertility problems to do so.)

And commercial surrogacy isn’t only illegal to take place in Australia. Residents of New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory and Queensland are also, by law, not allowed to pay a mother overseas to be a surrogate. (Residents of other states and territories are legally allowed to contract a woman overseas to be a commercial surrogate.)

But there is a growing appetite for commercial surrogacy here, says Jefford, who has had 100 people this year contact her to inquire about engaging a surrogate in countries like Mexico, Columbia, Cyprus, Greece and the United States.

“I think marriage equality helped gay dads see themselves in the picture, and see surrogacy as an option for growing their families,” says Jefford, adding that about half of her clients are gay couples, and half are straight people who are experiencing infertility.

The cost of commercial surrogacy is prohibitive – about $180,000 in the United States, and about $40,000-$60,000 in Mexico. This covers not just the surrogate’s fee, but the cost of IVF, the pregnant woman’s medical bills and airfares to and from the surrogate’s country.

”People will mortgage their homes, get a second mortgage, access their super, [forgo] a wedding, the whole lot,” says Jefford.

And, as much as people often refer to surrogacy as the luxurious choice of those who are “too posh to push”, the rest of the process is not easy, either.

Usually, a couple will go overseas to create their embryo via IVF in the country where their surrogate lives. Then the couple – or person, if they’re using a donor egg or sperm – will return to Australia, but go back overseas for the 20-week pregnancy scan, and then back again for the birth of the baby.

Bringing a baby born via surrogate overseas back into Australia can be difficult. Parents often have to apply for Australian citizenship for their newborn overseas, depending on which country they’re in. There can be hold-ups, due to paperwork mix-ups, delay or mistakes.

“I did hear of someone who was stuck in Georgia [the country] for six months after the birth of their baby,” says Jefford. “Sitting in a hotel with their newborn.”

Make the most of your health, relationships, fitness and nutrition with our Live Well newsletter. Get it in your inbox every Monday.

Most Viewed in Lifestyle

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article