The novelist Marcel Proust died a century ago, an anniversary that has generated many pieces, including the fine essay by David Free in last week’s Spectrum. My only question: why does no one mention how funny he was?

This, admittedly, is a bugbear of mine. Funny writers are looked down upon. Australia has been home to quite a few of them – CJ Dennis, Lennie Lower and Ross Campbell – but they’re never rated as highly as those who never crack a smile.

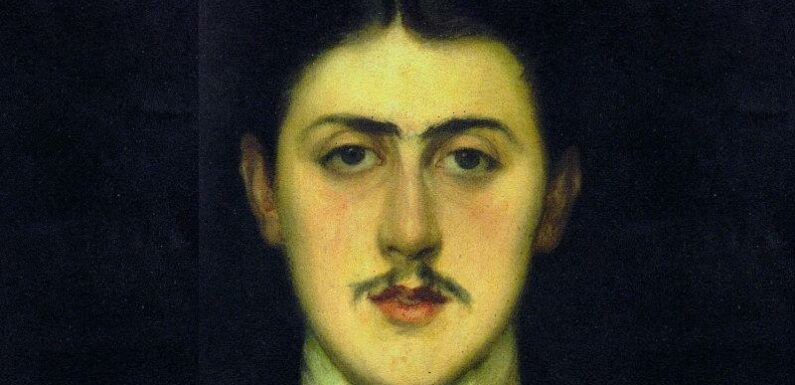

Marcel Proust: seriously funny guy.

In the literary world, the funny novel rarely wins. When Howard Jacobson won the Booker with The Finkler Question, it was the first time a funny book had won. I worship the man, and cheered on his victory, but still noticed it was his least funny book.

Why didn’t PG Wodehouse win the Nobel Prize? Why did Philip Roth win the Pulitzer for American Pastoral and not for Portnoy’s Complaint? Why isn’t the hilarious Barry Oakley as famous as Peter Carey, his fellow refugee from advertising? And why does no one mention how Thea Astley was as sharp as she was profound?

Which brings us back to Proust. Like any humourist, he writes about small things as if they were big things, and big things as if they were small things. He specialises in the absurdity of the human condition. And he’s not adverse to slapstick.

Take the example of the twin brothers whose faces resemble tomatoes. One of them is willing to accept money for sexual favours from “certain gentlemen”; the other is not. Alas, Monsieur Barnard keeps mistaking Tomato Number 2 for Tomato Number 1 and is given a regular black eye for his error.

The result is he develops an abhorrence of tomatoes. When a tomato dish is ordered in the local restaurant, he intervenes with his fellow patrons and tells them the dish is no good. By the end of the tourist season, the poor chef is left with a glut of tomatoes and no idea that his misfortune began with twin brothers, only one of whom was willing to accept work as a male prostitute.

Much of Proust’s masterpiece is similarly lewd, absurd and comic, so why is that tendency never mentioned? How come, a century on, he is reduced to the rank of “a serious writer”?

True, vast swathes of In Search of Lost Time are a meditation on memory, and how recalling something can prove more meaningful than the initial experience. There’s also more about the Dreyfus affair than can be reasonably tolerated.

Yet there’s also so much fun. Consider the feud between the cook and the kitchen maid, a battle fought through the weaponising of asparagus, a vegetable that gives the maid asthma.

Or the lecherous old man whose eyes still flit to watch a group of young women, “as though his eyes had not been notified of his removal from the active list”.

Or the bon vivant who ignores a dying relative in favour of a night out: the relative, the man assures himself, is “bound to regain his strength in due course”.

Despite its philosophising, Proust’s book is a social satire, built around grand set pieces in various Parisian salons, country homes and (in one case) a sadomasochistic homosexual brothel.

Proust sends up hosts who provide inadequate quantities of food – “dining there should be understood as taking a cure” – and mocks those who provide uncomfortable furniture in the Empire style. Just as Australians scoff at the wannabe grazier – “the bigger the hat, the smaller the property” – so Proust has a go at wannabe aristocrats: “the more doubtful the titles, the more space the coronets occupy on the glasses, the silver, the notepaper and the luggage”.

Even his philosophising has a comic edge, as when he criticises German philosophy as a poor imitation of the ancient Greeks: “it is the ‘Symposium’ all over again … but this time with sauerkraut and no rent boys”.

Proust is celebrated for his long sentences, clauses tucked inside clauses like Russian dolls. But he was also good at the quick parry: scorning the man who tries to prove his masculinity through a vice-like handshake; or the woman who sacrifices her face for a thin waist; or the moody friend who is “like one of those countries with which we dare not conclude an alliance because they change government too often”.

By concentrating on its philosophical passages, it’s also easy to miss the book’s sense of time and place. We share the moment when the telephone arrives, when an aeroplane is first spotted, and when a revolving door is encountered: “I became alarmed that I should never get out of it”.

Towards the end of In Search of Lost Time, Proust talks about how each reader creates their own book; a quite different book to that created by some other reader. As he puts it: “it’s possible to impute the difference between the two texts not to the author but to the reader”.

Maybe he has a point. In marking this centenary, readers around the world have celebrated Proust’s high-minded meditation on the meaning of life. Me? I find myself smiling at all the salacious slapstick.

Tomatoes, anyone?

To read more from Spectrum, visit our page here.

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from books editor Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.

Most Viewed in Culture

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article