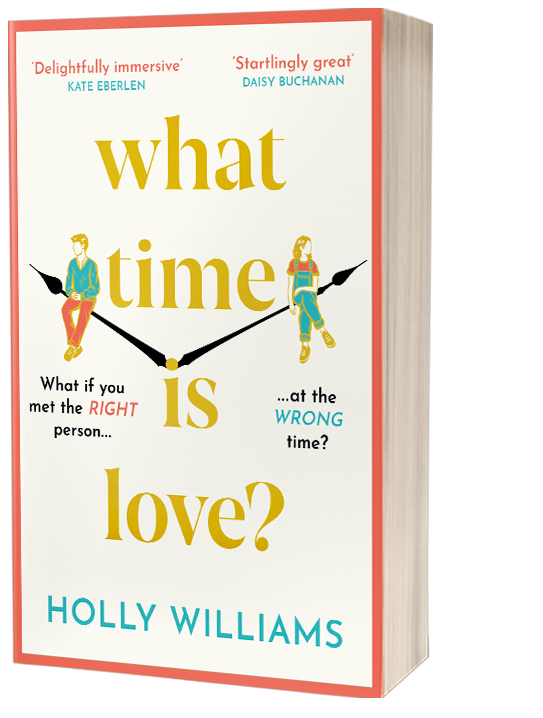

Written by Holly Williams

In her new novel It’s Time For Love, writer Holly Williams explores how class can divide romantic partnerships. Here, she explains why it’s as big an issue as ever in 2023.

Love across the divide is a common theme in romantic stories: whether it’s Pride And Prejudice, Wuthering Heights, The Notebook or Normal People, differences in wealth, status, family expectations and cultural capital in a relationship are reliably knotty territory.

And though these popular tales of romance often have us turning to the past to understand these dynamics, the divisive nature of class hasn’t exactly gone away in contemporary Britain. We might not be stuck in such rigid, forelock-tugging hierarchies as we once were, but according to recent research by York University, your class background is depressingly still a marker for how successful you’re likely to be later in life.

In fact, rather than class becoming less entrenched in society, we are living in an era where younger generations may be more class-bound:social mobility is decreasing for young people, according to research released last summer by the Sutton Trust. And if we’re more likely to stay in the class we were born in, we’re also more likely to date within that socio-economic bracket too. According to the Resolution Foundation, Brits still “tend to couple up with those who have similar inheritance expectations to their own”.

Meanwhile, recent research by Swedish sociologist Marie Bergström has discovered that class shows up as a factor in who we want to match with on dating apps. While many of us are open about searching for someone with similar tastes and values – sounds reasonable, right? – a certain class snobbery can often be smuggled within that. In her book The New Laws Of Love: Online Dating And The Privatisation Of Intimacy, Bergström explores how dating app users are often – consciously or subconsciously – filtering potential matches by class signifiers.

“It should come as no surprise that class discrimination occurs on dating apps. The codes – the ways people give and receive information on dating apps – will vary depending on their economic and cultural capital,” she explains, giving examples of a man who preferred elegantly posed, black-and-white photos to duck-pout selfies or a woman who discounted men for not crafting finely-written bios. Poor spelling is a particularly noted no-no.

“Condescending attitudes toward culturally underprivileged users are common,” Bergström found. “Judgments related to writing encompass the entire social hierarchy in values expressed by opposites: mature/immature, well-educated/crude, serious/lazy, intelligent/stupid, refined/vulgar, and so on.”

Tanya*, who is 29 and lives in London, remembers being shocked when the issue of class came up in her first relationship as a teenager with a boy in her school. “It was a private school, but there were a few people from very low-income backgrounds, and Jason was one. His family were very, very poor when he was younger – he lived in hostels.” Tanya was from an affluent, upper-middle-class family with a large house, and although she was aware of their differences, she didn’t think it was a problem. Until one day, in a sudden outburst, Jason accused her of being “spoilt”.

“I realised he had some opinions about me he hadn’t been sharing,” Tanya recalls; they’d been together a couple of years by this point. “I remember feeling very hurt by it, like it was a real attack.”

When Tanya went to university to study English, Jason started working as a labourer on a building site. And it was then that the cracks really started to grow. “He would come and visit, and he just hated everyone – he hated the culture there. It was so hard.”

Sometimes, however, class tensions simply come down to money. Even if you have identical tastes in Netflix docs and a matching Spotify Wrapped, disparities in how much wealth you’ve grown up around – or stand to inherit – can have a destabilising impact on a relationship.

Laura, 35, grew up in a working-class family in south Wales. She’s always gone halves with her partner, Stephen, over the eight years they’ve been together: splitting rent and bills, holidays and meals out. They earn roughly similar amounts and have similar tastes and expectations. But when Stephen inherited a significant chunk of money, the difference in their class backgrounds suddenly reared its ugly head.

Stephen wanted to put down a deposit on a house for them, which Laura baulked at. “I’m never going to inherit in the way that he has – I’m just not,” she says. At the moment, she doesn’t have much left over each month after paying rent and bills – certainly not enough to save anything like the amount Stephen inherited.

It’s led to difficult conversations because he can’t understand her position. But being equal in a relationship has always been very important to Laura and, while she trusts her partner, she’s still residually uneasy about him owning a much greater stake in their home. They now mostly avoid the topic – and still haven’t made a decision about the house.

It’s something Tanya has also experienced – but from the other side. Her current partner, Chris, also comes from a much less well-off background. They’ve been together two years, but are hoping to buy a house one day – when they do, she’ll pay for most of it.

“There will be a point where I’ll inherit a lot of money. My attitude is, ‘that is ours’ – we share it,” Tanya says. But she thinks it’s easier to be the generous one and recognises that, unless you are careful, it can feel like you have a hold over the other person. “I don’t think it goes away – the worry of that getting in the way of our relationship.”

But Chris and Tanya have learned to deal with that worry by being incredibly open. “Class is something we talk about all the time. With Jason, it was this unspoken thing – apart from random flare-ups – whereas Chris has said from day one that ‘I’ve never hung out with people with wealth like yours’.

While class has long been a fraught, defining feature of Britishness, perhaps class differences in relationships only really becomes a problem when allowed to grow in the dark: if we can be a little more conscious of our assumptions and prejudices while dating, and shed a little bit more light on our anxieties in relationships, it might not need to divide us after all.

Images: Getty; Holly Williams

Source: Read Full Article