By Chip Le Grand

Felix Metrikas, pictured with a Ukrainian nurse in Kharkiv, has been training troops since the early months of the war.

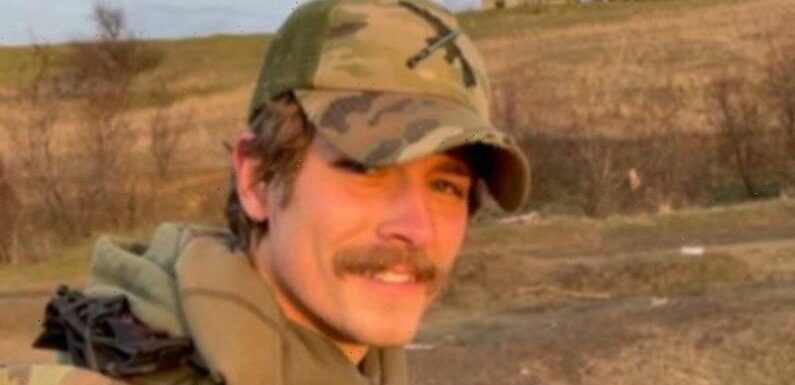

For Felix Metrikas, joining the war in Ukraine was a lot easier than leaving it.

After nine months providing training and supplies to Ukraine troops, a part of him is ready to return home to Geelong. Another part knows he can’t for a while yet.

On the anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Felix was in a small western Ukraine town waiting for mechanics patch up the Mitsubishi ute he was driving to the besieged city of Donetsk, where warmer weather and Russian reinforcements are likely to bring a fresh onslaught.

Felix, a 23-year-old former Army reservist, helps instruct troops near Rivne, in western Ukraine.

His time in Ukraine has changed his understanding of the war and the people fighting on both sides of a conflict which, for now, has reached a grisly stalemate. It has also made him realise that when he decided to travel to Ukraine, he had no idea what he was getting into or how poorly prepared he was.

Australian Federal Police officers who’d tracked his plans and intercepted him at Melbourne airport told him as much, but by then he was hard set, declaring to his father that he couldn’t sit around being a “slacktivist” when there were things he could do to help.

“They saw me as a naive young guy who was getting involved in something he wasn’t ready for, and that was true,” the 23-year-old former Army reservist says.

“I came here with illusions. I didn’t think I was invincible or it was going to be some sort of action movie, but it became obvious, after a few gut-wrenching moments, that I could die, and I realised I wasn’t as ready for that as I thought. The scariest part about this war is it is often about luck.”

Felix has a message for other Australians tempted to joint the fight: Don’t.

“It is hypocritical, but I would not encourage more people to come. To anyone who is considering it, this is worse than I thought it could be,” he said.

“I have had friends over here who have been killed. Guys with daughters of their own. An Australian [who died] waiting to be picked up by one of those Ladas.

Felix, from Geelong, has been in Ukraine since the early months of the war.

“The reality of this war is much more chaotic than what is being portrayed. I wasn’t ready for this kind of thing. I wish it wasn’t happening to the Ukrainian people.”

Felix still believes in what he is doing: that by sharing his training with Ukrainian recruits, who might otherwise be sent to the front with none, he may help some of them survive the war.

He also understands the terrible stress he has inflicted on his family in Melbourne and Geelong.

“I feel so bad for my family,” he says. “But I am just too invested to leave. If I went home right now I wouldn’t be OK with it.”

There is also a risk that when Felix does come home, he could find himself on the wrong side of Australia’s foreign incursion laws. The laws prohibit anyone from entering a foreign country with the intention to “engage in a hostile activity” unless serving with the armed forces of that country’s government.

It is unclear whether Felix’s activities in Ukraine have breached this provision. He says his involvement has been limited to training rather than fighting, first as a member of a private volunteer training group, the Trident Defense Initiative, that is personally endorsed by President Volodymr Zelensky and, more recently, attached to Ukraine’s 72nd battalion, a battle-worn mechanised infantry.

Jon Metrikas says he wishes his son was home but understands his reasons for joining the Ukraine war.Credit:Luis Ascui

Defence Minister Richard Marles declined to comment on Felix’s situation but his spokesman reiterated the government’s message to any Australian thinking about joining the conflict: “The travel advice is clear – do not travel to Ukraine.”

The AFP said it continued to monitor and engage with Australians who may be tempted to join the war.

“Australians who travel to Ukraine to fight with a non-government armed group on either side of the conflict – or recruit another person to do so – could be committing a criminal offence,” an AFP spokesperson said.

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade declined to provide an estimate of how many Australians are already in Ukraine. Four Australians are known to have died there during the year-long war.

Jon Metrikas, the son of a Lithuanian refugee who fled the Soviet occupation, said Felix was not a gun for hire but rather a considered young man determined to resist Russian President Vladimir Putin’s advance into Eastern Europe.

“I would prefer him not to be there but I fully understand it,” Jon says outside his business in Geelong, where he is arranging another shipment of fatigues and medical supplies to go to Ukraine. “Felix is on the right side of history.”

It was at the end of March last year, when Felix was visiting his mother Cheree Wood on the Mornington Peninsula, that he announced his intention to travel to Ukraine. Cheree says that in her shock, she agreed to drive Felix to the airport the next morning and spent the entire two-hour trip pleading for him to stay.

Felix’s plans were temporarily disrupted by AFP officers who pulled him out of the check-in queue. They didn’t arrest him, but sat him down and asked him questions until he missed his flight. For the next month, Jon, Cheree and their daughter Louise did what they could to try to change Felix’s mind.

There is a proud history of military service on both sides of Felix’s family. Jon served in the famed 4th/19th Light Horse Regiment and has Army buddies who went on to have long, decorated careers spanning multiple conflicts. They all told Felix the same things: this is not a game, you have to think of the impact on your family, you won’t have proper support on the ground, no amount of training or precautions can guarantee your safety.

“I wanted him to go into this with his eyes wide open” says a family friend who has experienced wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and Somalia and who, due to his current role, is unable to speak publicly. “War is f—ed,” he says, bluntly.

Felix pictured in Geelong shortly before he travelled to Ukraine.

Felix was not swayed. Although he listened to the advice, he also talked to cousins in Lithuania who remain fearful that if Russia succeeds in Ukraine, their country will be next. If he had any lingering doubts, they were removed when the Russians withdrew from towns such as Bucha and evidence of their atrocities emerged. “There was no stopping me getting on the plane that second time,” he says.

By then, Felix had finished his business course at RMIT, abandoned his plans to open a cafe with his dad, sold anything he had of value to fund his trip and donated the rest of his stuff to Ukraine charities. When AFP officers intervened for a second time at the airport, he politely called their bluff and boarded a flight to Berlin.

Kyiv was a ghost town when Felix arrived, but before long, he made connections with people who he now counts among his most trusted friends; an American-Ukrainian named Oleg Grabovyy, who established the Forever Ukraine charity, and Skye, an American-born nurse working in Britain who’d come to Kyiv to organise medical supplies.

Felix (left) with Oleg Grabovyy, an American-Ukrainian who established the Ukraine Forever charity.

Felix soon discovered that the most valuable thing he could offer was to teach recruits how to triage wounds and evacuate soldiers without everyone getting killed.

The 72nd battalion is currently holding the front line in Marinka, a suburb on the edge of Donestsk that has been largely reduced to rubble. Heavy casualties mean it is chiefly made up of inexperienced recruits, many of whom were drafted involuntarily into service. Felix says some are old enough to be his grandfather.

As for the enemy, he says that most of the estimated 200,000 Russian soldiers mobilised for the coming fighting season are people from poor areas and ethnic minorities. “I haven’t come to Ukraine because I am a crazy person who wants to kill Russians,” he says. “I am empathetic towards the Russian people who have been sent to a meat grinder.”

Felix with Ukrainian troops in Donetsk.

The Australian government marked the first anniversary of the war by announcing that a class of 200 Ukrainian soldiers had graduated from an ADF training course in the UK. Felix says the ADF training initiative is far better than anything he can provide. He also points out that the people he is training – soldiers on standby to join the front – can’t leave their posts to go to the UK.

That is why he is impatient to get his Mitsubishi on the road and rejoin his adopted unit. In the back of his mind he has a date, sometime between June and July, when he will go home. He fears that between now and then, a war already beyond his imagination will only worsen.

Get a note directly from our foreign correspondents on what’s making headlines around the world. Sign up for the weekly What in the World newsletter here.

Most Viewed in National

Source: Read Full Article