“Give me screaming kids any day after this experience,” Kathleen Megan Folbigg wrote in a letter from prison to a childhood friend. “So keep that in mind if you reach your witts [sic] end – Ha!”

It was 2003. Folbigg was 35 and facing a decades-long stint in Silverwater Women’s Correctional Centre over the deaths of her four young children between 1989 and 1999.

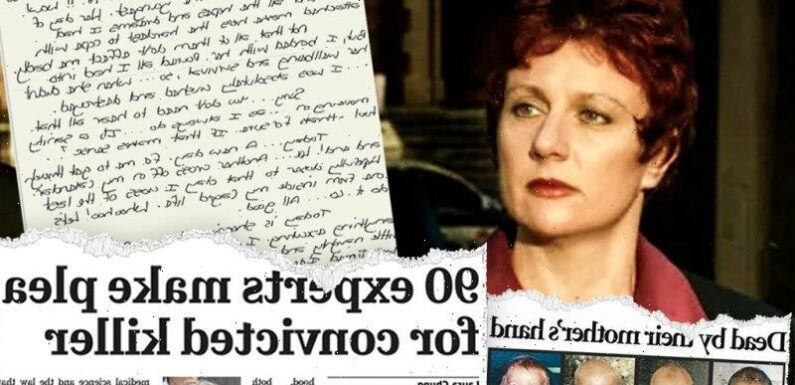

Clockwise from left: Kathleen Folbigg outside the NSW Supreme Court in 2003, an extract from her letters to her best friend Tracy Chapman, and newspaper articles on her conviction and subsequent push by experts for a pardon.

The handwritten note was part of a trove of letters from Folbigg to her best friend, Tracy Chapman, released this week by the judicial inquiry into her convictions for the murder of three of her children, Patrick, Sarah and Laura, and the manslaughter of her first child, Caleb.

A “medical or genetic miricle [sic]” might save her from languishing in prison, she mused to Chapman in 2003.

A scientific breakthrough

Fifteen years later, those words proved prescient. DNA sequencing and analysis in 2018 and 2019 revealed Folbigg and her daughters shared a novel variant in a gene that produces the calmodulin protein, CALM2, which controls the movement of calcium in heart cells.

The variant, G114R, was not found in Caleb or Patrick. Recent research suggests the variant may cause cardiac arrhythmias – irregular heart rhythms – and sudden unexpected death.

An extract of a letter from Kathleen Folbigg to Tracy Chapman, dated 2003.

A 2019 inquiry into Folbigg’s convictions, headed by former NSW District Court chief judge Reg Blanch, KC, heard evidence about the mutation. One team of experts, based in Sydney, concluded the genetic variant was of “uncertain significance”.

A separate team of experts in Canberra concluded it was “likely pathogenic”, or likely to cause disease.

Blanch preferred the evidence of the Sydney team and concluded there was “no reasonable possibility” the variant caused the deaths of Sarah or Laura.

Extract from a letter from Kathleen Folbigg to Tracy Chapman in which she refers to a “genetic miricle [sic]“.

The evidence as a whole, including Folbigg’s testimony at the inquiry about diary entries referring to her children’s deaths, “makes her guilt of these offences even more certain”, Blanch said in his July 2019 report.

“The only conclusion reasonably open is that somebody intentionally caused harm to the children, and smothering was the obvious method. The evidence pointed to no person other than Ms Folbigg.”

An alternative hypothesis

It was not until March 2021 that a journal article co-written by the Canberra experts, among dozens of international authors, was published. They concluded that calmodulinopathy, a life-threatening arrhythmia syndrome, “emerges as a reasonable explanation for a natural cause” of death for the Folbigg girls.

A new inquiry, ordered in May 2022 and headed by former NSW chief justice Tom Bathurst, KC, is considering whether there is a reasonable doubt about Folbigg’s guilt in light of those developments.

No expert giving evidence before the inquiry has ruled out the possibility the variant caused the deaths of Sarah or Laura Folbigg. But they are sharply divided on whether it is likely.

A circumstantial case

The jury deliberated for eight hours after a seven-week trial in the Darlinghurst Supreme Court, an imposing sandstone building in inner-city Sydney, before finding Folbigg guilty on May 21, 2003, of the murder of three of her children and the manslaughter of her firstborn child.

The prosecution had emphasised the unlikelihood of four children from the same family dying of natural causes within a 10-year period. Crown prosecutor Mark Tedeschi, KC, submitted to the jury: “It has never been recorded that the same person has been hit by lightning four times.”

Each child, aged between 19 days and 18 months, died suddenly in the family home between 1989 and 1999. Folbigg and her then-husband Craig moved during that time from Newcastle to Maitland and then to Singleton.

Post-mortems “failed to establish exactly what had caused the cessation of breathing” in each child, the Court of Criminal Appeal would say years later.

The Crown case was circumstantial and relied heavily on diary entries penned by Folbigg between 1989 and 1999, including an entry in January 1998 that said she was “short tempered and cruel sometimes to [Sarah] … and she left. With a bit of help”.

Folbigg wrote to Chapman in 2003: “I reckon they need to ban convicting people for ‘thoughts’. How they got away with using them against me is still amazing to me.”

In a separate letter on May 1, 2005, Folbigg told Chapman she used her diary to “‘dump’ every negative emotion, feeling, thought I’ve ever had”.

References to her black moods referred to depression, she said, and not “black as in evil or nasty or murderous”.

By February 2005, Folbigg had lost an appeal over her convictions but secured a reduction in her prison sentence from a maximum of 40 years to 30 years, with the non-parole period cut by five years to 25 years. She is eligible to apply for parole in April 2028, shortly before her 61st birthday in June.

For Folbigg and her supporters, it is too long to wait.

A reasonable doubt?

Professor Carola Garcia de Vinuesa, an immunologist and geneticist, discovered the novel genetic variant in Folbigg and her daughters with her then-colleague Professor Todor Arsov. At the request of Folbigg’s lawyers, she prepared a December 2018 report about the results of the genetic sequencing.

Both Vinuesa and Arsov were then at the Australian National University in Canberra, and they would form part of the Canberra team of experts who assisted the first inquiry in 2019.

Professor Carola Garcia de Vinuesa, centre, arriving at the Kathleen Folbigg inquiry in Sydney on Tuesday.Credit:Louise Kennerley

Vinuesa was questioned at the fresh inquiry on Wednesday about her public comments on the Folbigg case, including a tweet in December 2021 that it was “very sad … Kathleen will spend another Christmas in prison despite the overwhelming evidence that all her children died of natural causes”.

Tweet from Professor Carola Garcia de Vinuesa published in December 2021.Credit:Twitter

“I am allowed to feel empathy. If I am convinced of my science, then the logical thinking about this is that she shouldn’t be in prison,” Vinuesa told the inquiry.

Vinuesa conceded on Wednesday that, while it was possible a separate, rare genetic variant found in the Folbigg boys – linked to epilepsy – caused their deaths, too little was known about it to date.

She agreed she felt sympathy for Folbigg but insisted she separated her personal opinion from her scientific work, and said her chief contribution to the inquiry was “the initial finding of the calmodulin mutation”.

“The evidence I have provided cannot be manipulated. You can test it; you can find this mutation.”

Professors Michael Toft Overgaard and Mette Nyegaard outside the Folbigg inquiry in Sydney last year.Credit:James Alcock

Nine experts, including Vinuesa, have testified so far that it was possible the variant explained Sarah and Laura’s deaths by natural causes.

Danish research scientists Professor Michael Toft Overgaard and Professor Mette Nyegaard, who co-authored the 2021 journal article with Vinuesa and others, went as far as to say it was likely the girls died because of the variant.

In the absence of another identifiable cause of death, “the presence of that mutation is a very valid explanation” for their deaths, said another co-author, internationally renowned cardiologist Professor Peter J. Schwartz.

Professor Edwin Kirk leaves the inquiry in Sydney on Thursday.Credit:Nick Moir

Others were less sure. Professor Edwin Kirk, a clinical geneticist at Sydney Children’s Hospital, was on the Sydney team that assisted the first inquiry. He said it was “possible” the variant “could have caused the deaths” of Sarah and Laura, but he did not have enough evidence to say it was likely.

Professor Arthur Wilde, another internationally renowned cardiologist, said he could not exclude the possibility the mutation caused the girls’ deaths but he considered it unlikely, “even highly unlikely”.

Calum MacRae, a professor of medicine and cardiology at Harvard Medical School, said it was “a possibility, but I don’t think any of the evidence [to date] suggests that it’s a reasonable possibility”.

“At the moment there’s no evidence one way or the other,” he said.

A weighty task

Bathurst must weigh the evidence as a whole, including testimony yet to be heard about Folbigg’s diary entries. If there is reasonable doubt about Folbigg’s guilt, Bathurst may refer the case to the Court of Criminal Appeal to consider whether her convictions should be quashed.

On Monday, the words seemed to hang in the air when Bathurst asked counsel assisting the inquiry, Sophie Callan, SC, if “a reasonable hypothesis inconsistent with guilt” arose from the genetic evidence, viewed in isolation.

Callan paused.

“Yes, your honour,” she replied.

The inquiry continues next week.

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article