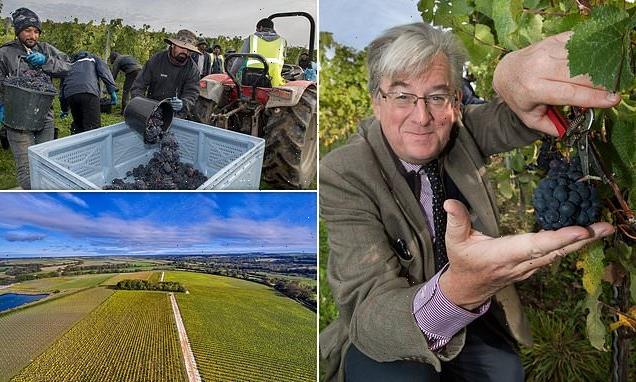

ROBERT HARDMAN: How the biggest names in French fizz are muscling in on BRITISH vineyards – with land in Kent and Hampshire leaving Tattinger and Pommery bosses swooning over the best crop in a decade

The harvest is over, the grapes are in and the verdict is positively euphoric: this is a truly vintage crop, easily the best in a decade.

So says Julien Lonneux of Champagne Pommery plucking a fat, blue-black Meunier variety off one of the vines which stretch down his valley in perfect lines, as the 2022 harvest comes to a close. And since the Pommery group includes some of the most famous names in champagne, Julien speaks with very considerable authority.

I hear exactly the same response from Christelle Ranville of Champagne Taittinger (and previously of Laurent Perrier) as she chews on an equally plump, round morsel of Pinot Noir.

Except, we are nowhere near the French cities of Reims or Epernay or the 132 square miles of farmland which surround them – the only place on earth officially allowed to call itself ‘Champagne’.

Robert Hardman visits the Domaine Evremond Vineyard in Kent where the Champagne Taittinger is being produced

Instead, I have been talking to Christelle in a field in Kent. Julien, meanwhile, has been supervising the grape harvest on the Pommery vineyards in Hampshire.

As many of the biggest names in the French wine industry now readily acknowledge, the really exciting new frontier of fizz is not in France but in South East England. And things are suddenly advancing at a very substantial pace.

For the boundaries of the wine-growing region of Champagne are strictly defined and its 280,000 vineyards are full to capacity already. Nor can it produce enough of its namesake to satisfy global demand. And global warming is starting to take its toll. Grape harvests, Julien Lennoux points out, now take place, on average, two weeks earlier than in the Sixties or Seventies.

At the same time, however, the weather patterns which have historically proved ideal for producing sparkling white wine in northern France, according to the traditional ‘methode champenoise’, have been steadily moving further north still, across the Channel. The conditions which once made for a great vintage in Reims now apply to the fertile seam of chalk which runs from Kent across to Hampshire.

ROBERT HARDMAN: As many of the biggest names in the French wine industry now readily acknowledge, the really exciting new frontier of fizz is not in France but in South East England. And things are suddenly advancing at a very substantial pace

The net result is that British wines in general are getting better and better. Climate change may have few upsides – but here is one, I suppose.

Until the Eighties, English and Welsh wines would be routinely, if unkindly, dismissed as undrinkable plonk for the staunchly patriotic or the eccentric. Since the turn of the millennium, though, both quality and quantity have been on a steep upward trajectory with home-grown wines – both still and sparkling – regularly picking up major awards. Production is now around nine million bottles per year, two thirds of them fizz.

‘Bottles that I have been experiencing over the past 18 months have been nothing short of superb,’ says veteran London merchant and wine writer Mark Roberts, of Decorum Vintners, ‘with an ideal balance between the fruit and acidity, allied to depth and complexity: distinctly different beasts to those that I had encountered over 20+ years ago.’

The ultimate compliment, however, is now to be found not in a glass but in the big construction sites currently underway in Hampshire and Kent. For it is here that these revered French champagne houses are no longer just dabbling. They are building brand new multi-million pound wineries.

The Louis Pommery Vineyard in Alresford Hampshire. French champagne companies are looking to produce fizz through British vineyards

Meanwhile, out on the south-facing slopes of the Home Counties, we are hearing more and more French accents. Last month, Champagne picked its grapes. This month, the focus shifted to England (where cooler maritime temperatures mean a later harvest than in France). Last year’s crop was something of a disaster in Champagne, thanks to early frosts. England, on the other hand, fared much better.

This year, the growers in Champagne have reported stellar yields. And it has been the same here in southern England.

‘It’s all down to climate and that has been ideal this year,’ says Julien Lonneux. ‘There has been very little frost, just enough rain in the early summer but a lot of dry days all through June and July when grapes can pick up disease if it is wet. And now the levels of sugar and acidity are just right.’

The harvest is over, the grapes are in and the verdict is positively euphoric: this is a truly vintage crop, easily the best in a decade, so says Julien Lonneux (pictured) of Champagne Pommery

It was less than a decade ago that Paul-Francois Vranken, owner of the Champagne Vranken-Pommery Monopole empire, was driving through Hampshire with some of his executives when it occurred to them that this could be an ideal place to make quality sparkling wine. The company had already been exploring similar ventures as far afield as South America and Mr Vranken’s native Belgium, but they were impressed by the quality of wines already produced by a smattering of vineyards in Hampshire.

In 2016, they bought the Pinglestone estate, near Alresford. In 2017, they started covering this former arable farmland with vines producing the three main grape types which go into the production of champagne: Pinot Noir, Meunier and Chardonnay. It would be another three years before these would deliver their first harvest, which was then set aside for blending with future growths, as happens in Champagne.

In the meantime, the company started buying in grapes from surrounding vineyards to start experimenting and producing their own sparkling wine under the name ‘Louis Pommery’, after the company’s 19th Century founder. By 2024, if things go to plan, then its entire English output will come from its own Pinglestone vines with a future production target of 200,000 bottles per year.

Jim Bowerman is the manager for Louis Pommery at the Hampshire vineyard. He has learned his trade in wine estates from the south of France to California’s Napa Valley and is thrilled to receive all this accumulated know-how from the French

Julien Lonneux is adamant that this is not some sort of Gallic takeover. ‘We have come here in a spirit of humility. We want to learn from scratch. We are coming at this with an entrepreneurial mindset,’ he explains, as a team of Romanian pickers comb the slopes with their secateurs.

The idea is not to produce something identical to champagne but a sparkling wine of the same quality with its own identity. During a brief lunchtime downpour, we adjourn to a delightful 15th Century barn where he pours me a glass of his latest Louis Pommery, a light, zingy number with a hint of apple. Perfect with a smoked salmon sandwich.

The Pommery team are working closely alongside British vineyard manager, Jim Bowerman. He has learned his trade in wine estates from the south of France to California’s Napa Valley and is thrilled to receive all this accumulated know-how from the French. ‘They bring this wealth of knowledge about blending different vintages whereas, I think, in Britain, the tendency has been to bottle whatever you get each year and just sell it,’ he says.

ROBERT HARDMAN: There has been a properly French atmosphere over in Kent at Domaine Evremond, the new joint venture between Champagne Taittinger and British wine brokers, Hatch Mansfield

There has been a properly French atmosphere over in Kent at Domaine Evremond, the new joint venture between Champagne Taittinger and British wine brokers, Hatch Mansfield.

Here, I saw everything stop – French-style – for lunch. And not just any old lunch. The team from France brought their own platters of meat and a barebcue, pausing mid-harvest for faux-filet steaks and merguez sausages plus a glass of red wine. Very civilised.

Once again, this has been a shared pooling of international knowledge rather than a French lesson. It was in 2015 that Pierre-Emmanuel Taittinger began talks with British wine broker, Patrick McGrath of Hatch Mansfield, about making wine in Britain.

The Taittingers favoured Kent, not least because Pierre-Emmanuel’s father was also the mayor of Reims who twinned his city with Canterbury half a century back. This would not be a clone operation but an entirely new adventure in need of a new title. The Taittingers hit upon the name Evremond, after Charles de Saint-Evremond, a 17th-Century French diplomat who helped introduce champagne to England and is buried in Westminster Abbey.

It would not just be a simple question of buying a few fields. They needed very specific ground – southerly-facing, gently-sloping farmland with the right soil, wind and water. Eventually, they acquired 100 acres near the village of Chilham from fourth-generation local fruit farmer Mark Gaskain who remains a key part of the Domaine Evremond team.

Zam Baring, 58, runs The Grange – a thriving family-run vineyard and brand new £1.5 million winery near Alresford in Hampshire

He tends the vines all year round in between regular team visits from Taittinger, including Christelle Ranville, who has been directing this year’s harvest.

‘You don’t just go from one field to the next,’ she explains. ‘You follow the fruit.’ As well as testing samples for levels of acidity and sugar, she is always guided by her own tastebuds. ‘I can feel real flavour there,’ she says, mulling over a juicy Meunier. ‘All the parameters are exactly right now.’ I pick one, too. It looks more like an obese blueberry than the grapes we find in our supermarkets. There is a pleasing sharpness as it bursts followed by an almost syrupy sweetness. ‘Wait one or two weeks more and we could have a lot of rot there,’ explains Christelle.

All this year’s juice will be fermented and stored for future blending, with a view to selling the first bottles of Domaine Evremond in 2024. On the skyline, I see the cranes and diggers building the brand new factory which will do this job in future.

ROBERT HARDMAN: It may take a little longer before Britain realises the range of top quality fizz grown on its own doorstep. But it will come, as surely as it has already happened in places like Australia and New Zealand

So how do the locals feel about this French invasion? ‘Thank God, the French are here. Because I think it’s the ultimate validation that we are all doing the right thing,’ says Zam Baring, 58, of The Grange, a thriving family-run vineyard near Alresford in Hampshire.

Here, I find a spotless, brand new £1.5 million winery, built into the side of a chalk slope. Zam walks me through his shiny storage hall, lined with oak barrels from Champagne and gleaming new fermentation vats from Germany. Here is a very clear sign of the way British wine is going.

I try the ‘Grange Classic’ followed by a glass of the ‘Grange Pink’, an elegantly subtle shade of rose. Both are right up there with their counterparts from Champagne. They are priced accordingly at around the £30 mark, but with good reason. For a magnum of Zam’s 2016 ‘Grange Classic’ has just won a gold medal at the 2022 Champagne and Sparkling Wine World Championships.

It may take a little longer before Britain realises the range of top quality fizz grown on its own doorstep. But it will come, as surely as it has already happened in places like Australia and New Zealand.

Or take the Prosecco market. Ten years ago, few people touched the stuff outside Italy. Now you can’t move for Prosecco promotions in every British pub and wine bar.

After France and the USA, the UK is the world’s next biggest guzzler of champagne.

Given the state of the pound and the direction of the economy, we may be buying British rather sooner than expected.

Source: Read Full Article