Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

A few days ago, just over 200 of an elite group of investigators gathered – generations of murder detectives, with the oldest aged 93, to mark the 80th anniversary of Victoria’s homicide squad.

There were detectives who had been at the squad a few months and men on walking frames who locked up killers in the 1960s. They had a shared bond – investigating the most devastating crime on the books.

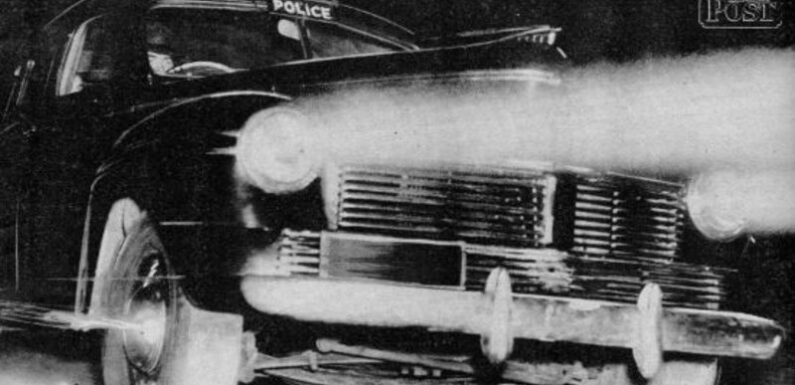

A 1946 Australasian Post profile on the homicide squad. (Not written by your correspondent.)

Many of us at different times think our job is a matter of life and death. The difference is theirs is a matter of life and death. Their work has sparked TV dramas and documentaries, dozens of books (including the about-to-be-released Naked City – a classic of its genre) and a long list of podcasts.

The rules and the investigative techniques might change, but the job doesn’t.

So what makes a good homicide detective? Stamina, as they must be prepared to work up to 20 hours a day; compassion, because they must counsel the victim’s families while trying to find the killer; a sense of humour to survive what they have to see; and empathy to interview a suspect in a manner that encourages them to talk.

Since it was formed in 1943 with a strength of six detectives the squad has investigated more than 4500 homicides; dealt with six gangland wars; caught serial killers and mass murderers; and solved cold cases decades after the offenders would have believed they were home free.

Police search for weapons during a dawn raid in 1964 on Victoria Market as part of an investigations into mafia-style shootings.Credit: Ken Wheeler

When the squad started, there were about 21 murders a year. Now the figure is around 90.

Through the ranks have been three chief commissioners, one Tasmanian police commissioner, 18 assistant and deputy commissioners, four Police Association secretaries and one emergency services commissioner.

One of the squad’s first cases, according to police unofficial historian Ralph Stavely, was a taxi driver found shot dead in Prahran. The giveaway was a US soldier’s hat, complete with his name written on the inside, found in the abandoned taxi. It would have been an open-and-shut case if the suspect’s fellow troops hadn’t provided an alibi.

Brownout Strangler Eddie Leonski.

“A year or two later Charlie Petty (the lead detective) was contacted by one of the Yanks he had interviewed, and this person said (off the record) you don’t have to worry about him any more – the Japs got him,” says Stavely.

The squad was almost certainly formed in response to the hunt for the man who may have been Victoria’s first serial killer – US soldier Eddie Leonski – who was known as the Brownout Strangler because he struck at night when Melbourne’s lights were dimmed under World War II rules.

In 15 days during May 1942, Leonski murdered three women. Although Victorian detectives gathered the evidence and arrested him, he was court-martialled by a US military court. His execution papers were signed by General Douglas MacArthur, and he was hanged in Pentridge Prison.

About 50 years later, another serial killer murdered three women in Frankston. It was the homicide squad that found, arrested and brought about the conviction of Paul Charles Denyer, who is now lobbying to be freed. The rule is pretty simple. You catch a serial killer to bring them to justice but also to stop them from striking again.

By the 1950s, the small squad started to investigate underworld murders. Then, as is the case now, detectives were faced with trying to crack the so-called code of silence.

The shooter and the victim: John Twist (hatless) with Freddie Harrison (middle). Twist was the gunman who years later shot Harrison.Credit:

After an underworld non-fatal shooting the payback was quick and bloody.

On February 6, 1958, the most feared gangster of his time, Freddie “The Frog” Harrison, pulled up at South Wharf in his 1953 Ford Customline to pick up his pay and return a borrowed trailer. As he was uncoupling the trailer, in the shadows of the ship the River Murchison, a gunman pulled out a shotgun and said, “This is yours, Fred,” shooting his target in the head.

There were 30 men near the car, yet no one apparently saw anything. About 12 potential witnesses declared they were in the toilet at the time. It was a two-man toilet. The frustrated coroner threatened to have the toilet reconstructed in the court and invite all the reluctant witnesses to show how they fitted into the ablutions block.

One witness who was with Fred said that when he heard the shot he immediately turned his head right. The gunman was on his left.

One of the veterans at the squad’s anniversary dinner was former assistant commissioner Reg Baker, who compiled the brief of evidence against Ronald Ryan, hanged in Pentridge Prison in 1967, the last man executed in Australia,

Ryan’s case took 12 sitting days. Today a homicide prosecution brief is at least 20 volumes.

The squad began with typewriters, unsigned statements from suspects (leaving room for doctored confessions), unsworn statements from the dock, where an accused could give a version of events without facing cross-examination or perjury charges, no DNA, no phone taps and no mobile phone pings.

It has investigated paid hits, horrible family violence, abductions, mistaken-identity murders, stabbings, shootings, poisonings, stranglings and suffocations.

Detectives have found bodies in barrels, burnt-out cars, acid baths, bush graves and tips, and a head in a kerosene tin dumped in the Barwon River.

They wore hats and scowls and the squad was all male.

Until we started leaving electronic footprints, it was almost impossible to gain a murder conviction without a body. Now we have a specialist missing person’s squad that works on cases where the victim has not been found.

The head of the squad, Detective Inspector Dean Thomas, said after the dinner, “It is important to recognise the former members who forged our legacy. If we are to move forward we have to know where we have come from.”

The oldest person at the anniversary dinner was Nick Cecil, one of the first non-Anglo Australian recruits in the police force. Nick became Victoria’s first undercover operative, masquerading as a guitar-playing busker in country pubs working for Mick Miller’s SP busting special duties gaming branch back in the 1950s.

Cop Nick Cecil and crook Ronald Biggs

He was seconded to the homicide squad to work on ethnic-related murders, and built a network of informers who would not talk to traditional Australian cops.

In 1969, he was ordered to follow Charmian Biggs, the wife of fugitive British Great Train Robber Ronald Biggs. One day, she said: “Nick, believe me, he’s gone. He’s left Australia.” After hiding for months, Biggs sailed to Panama using an altered passport and moved to Brazil.

The first female homicide investigator was Jennifer Ann Wiltshire, who served in the squad from July 1993 to November 1995.

Police raid Victoria Market in the 1960s.Credit: Jack Faithfull

Now there is a female four-person serious crime response team, one of the on-call units first sent to a murder scene.

It was the homicide squad that was tasked with dealing with the 1963-64 Market Murders involving the killing of three fruit and vegetable merchants and the shooting of three others.

When the Honoured Society godfather, Domenico Italiano, died of natural causes, there was a power struggle settled with shotguns. One of the victims, Vincenzo Muratore, was shot dead outside his Hampton home in 1964.

Nearly 30 years later, his son Alfonso was killed in similar circumstances – just 1.5 kilometres away – outside his Hampton home.

After the market murders, Liborio Benvenuto became godfather. He died of natural causes. His son, Frank Benvenuto, was shot dead in 2000 near his Beaumaris home.

Mafia buster John T. Cusack (middle row, fourth from left) at a farewell dinner with homicide detectives in 1964.

In response to the Market Murders, the government sent for US mafia expert John T. Cusack, who was embedded with the homicide squad.

In his report he found: “Within the next 25 years, if unchecked, the society is capable of diversification into all facets of organised crime and legitimate business.”

Twenty years ago, we went through the Underbelly Wars, where crooks who were making millions let their egos get in the way of profits and began killing each other.

An off-shoot of the homicide squad, the Purana taskforce, along with then director of public prosecutions Paul Coghlan (who was guest speaker at the anniversary dinner), broke the code of silence, leaving most of the main players dead or in jail.

In the early 2000s, crew boss Jeff Maher (white shirt, middle) and squad boss Brian Rix (dark shirt) discuss an ongoing job.

Nearly 60 years after Cusack delivered his report, he has been proved right. Organised crime has jumped all police geographical firebreaks, with two syndicates fighting for illicit markets that include drugs and black market cigarettes.

The gangs are no longer suburban or even national; they are international. Cash, drugs and even hitmen flow across national borders. To compare, say, the Painters and Dockers war of the 1970s with the Middle Eastern crime syndicates’ power struggle would be like comparing morse code with the internet.

One syndicate is making $10 million a week, with its bosses, now in the Middle East, capable of ordering multiple firebombings of tobacco shops and murders in Melbourne.

Generations of homicide investigators know that while techniques used to investigate murders change, two rules remain constant when dealing with the underworld.

Some things never change and crooks don’t learn from the past.

Naked City – the book. Pan Macmillan. Available October 31. What the critics say: “Dear John, May the Yuletide log fall from your fireplace and burn your house down.” Standover man Mark Brandon “Chopper” Read.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article