Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

New York: In 2013, Mirsad Kandic began working with the Islamic State group, helping to advance its campaign of global jihad.

Over the next four years, he fought in at least one battle and operated from safe houses in Syria, Turkey and Bosnia, federal prosecutors said, spreading propaganda and controlling a network of pro-Islamic State Twitter accounts. He was also said to have funnelled money, weapons, equipment and false identifications to the group’s fighters.

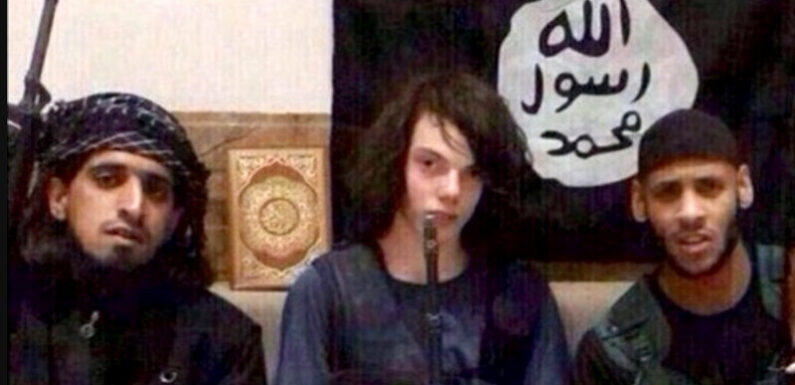

Australian Jake Bilardi (centre) alongside two Islamic State members.Credit: Twitter

And, prosecutors said, he played a role in recruiting or trafficking many of those fighters, including an Australian teenager named Jake Bilardi, who eventually died as a suicide bomber in Iraq.

Last year a jury in Brooklyn found Kandic, who had lived there and in the Bronx before travelling overseas, guilty of conspiracy and of providing material support to the Islamic State group. On Friday, he was sentenced to life in prison by Judge Nicholas G. Garaufis of the US District Court in Brooklyn.

A prosecutor, J. Matthew Haggans, told Garaufis before the sentencing that Kandic had zealously embraced the Islamic State group’s deadly theology, which had affected millions of people.

“He was a merchant of death and destruction,” Haggans said. “He was a global terrorist for a global terror organisation at its zenith.”

A defence lawyer, David Stern, asked for leniency, urging the judge to send a message that “we have a shred of mercy for every human being and we believe in change”.

Just before being sentenced, Kandic spoke, telling the judge he was not a violent person and had not harmed anyone but adding: “I do seek forgiveness.”

Moments later, Garaufis described Kandic’s behaviour as “extreme” and “unfathomable”, saying he had turned beliefs “into hatred and murder” on a “grand scale”.

“Jake Bilardi did not deserve to die,” Garaufis said. “And he did not deserve to kill anyone.”

Kandic, a citizen of Kosovo and a legal permanent resident of the United States, was one of thousands of radicalised figures from dozens of countries who travelled to the Middle East to join the Islamic State, a brutal group known for forcing women into sexual slavery and for drowning, burning and beheading prisoners.

Although he was placed on a no-fly list and prevented twice from boarding flights to Europe, Kandic was able to leave the United States for Istanbul in 2013, taking a complicated route that included stops in Texas, Mexico, Panama, Brazil, Portugal and Germany.

Upon arrival in Islamic State territory, prosecutors said, Kandic joined a brigade of mostly foreign fighters, called Jaish al-Muhajireen wal-Ansar and led at the time by a Georgian national, Omar al-Shishani, who served as the Islamic State’s minister of war.

He also established relationships with Islamic State group leaders like Abu Luqman, the group’s governor of Raqqa province, and Bajro Ikanovic, a Bosnian national who ran a training camp for recruits in northern Syria, prosecutors said. Evidence introduced at trial by prosecutors showed that Kandic relayed “battlefield intelligence” to Ikanovic and once alerted him to the presence of “a spy” in Mosul, Iraq.

Starting in 2014, prosecutors said, Kandic was based in Istanbul. He worked in what he called the Islamic State’s “media department,” prosecutors said, running dozens of Twitter accounts that spread the group’s propaganda, including a video called “Flames of War” that showed the executions of Islamic State enemies.

Kandic also used social media to recruit people to join the group, according to prosecutors, letting those aspiring fighters stay in a “safe house” he maintained in Istanbul, helping them obtain bogus Turkish and Syrian identity cards and sending them to Syria, Afghanistan, Libya, Sudan, Somalia and Egypt.

One of those whom Kandic is said to have shepherded was Bilardi, who prosecutors said searched for the term “Turkey-Syria border smugglers” in the summer of 2014, when he was 17 and living on the outskirts of Melbourne, Australia.

Within roughly two days, Bilardi had found his way online to Kandic, who prosecutors said guided him over the course of weeks, giving him advice on items to bring with him from Australia and specific instructions on where to go in Istanbul after arriving there by plane.

Bilardi joined the Islamic State group in Syria by late 2014 and later credited Kandic’s assistance, prosecutors said, adding that the two stayed in touch for months as Bilardi fought in battles and prepared for a suicide mission.

That attack came in the spring of 2015, one of several that took place that day in Anbar province, prosecutors wrote. They involved at least 11 suicide bombers, killed more than 30 people and preceded an Islamic State takeover of that region two months later.

Communications intercepted by the Iraqi military showed that other Islamic State fighters had “congratulated” Bilardi for the “success” of his attack and that the group had issued “condolences” for his death, prosecutors wrote.

Prosecutors added that Kandic had spoken up about Bilardi’s “martyrdom operation,” referring to him on Twitter as a “lion” who had killed and wounded many “kufar”, a derogatory term for nonbelievers.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Get a note directly from our foreign correspondents on what’s making headlines around the world. Sign up for the weekly What in the World newsletter here.

Most Viewed in World

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article