Ben had a wholesome upbringing and was adored by his middle-class parents. But here the mother who found him dead in a squalid hostel says his tragic story is…Proof no child is beyond county lines gangs

Towards the end of the agonisingly long and drawn-out inquest into the death of 16-year-old Ben Nelson-Roux, a poignant video was played in the coroner’s court, at his parents’ request.

Overlain with tributes from his friends and his maths tutor, it showed an exuberant boy enjoying a wholesome upbringing in the most affluent part of Yorkshire.

Here was Ben, enjoying outdoorsy holidays with his father, Barry Nelson, 57, a global operations manager with Mastercard, and mother, Kate Roux, 47, a massage therapist and Tai Chi teacher, who responsibly and lovingly co-parented him after their separation.

There he was, driving a tractor during a carefree weekend on the Wensleydale farm run by his beloved Uncle Willie, who always let him wear his overly-long, brown overcoat.

A coat that Ben liked so much that his parents — who gave him a natural funeral in the countryside and adorned his coffin with his favourite bird, a red kite — decided he should be dressed in it when they laid him to rest. The contrast between the boy we saw in that film and the anguished teenager he had become by the time his mother found him, lying lifeless on his bed in a squalid homeless hostel, is almost unfathomable.

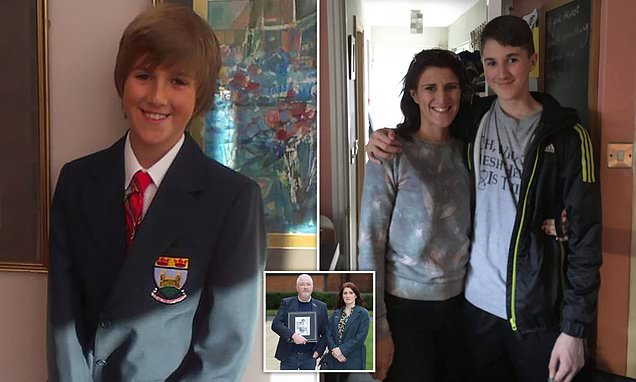

Ben Nelson-Roux (pictured) was found dead at a hostel for homeless adults in April 2020

It serves as a grim reminder of the catastrophic consequences when any young person — and particularly someone as vulnerable as Ben, who suffered from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) — falls into the clutches of a County Lines drugs gang.

According to a recent government report, these predatory syndicates have ensnared tens of thousands of children, some of primary school age, and now pervade virtually every corner of Britain.

The inquest into Ben’s death ended on Monday. Having heard that he had taken cocaine, cannabis and ecstasy, North Yorkshire Senior Coroner Jon Heath decided that he had probably died of multiple drug use.

However, the precise cause could not be established because Ben died during the Covid pandemic, in April 2020, and an intrusive post-mortem examination was not carried out.

Mr Heath said Ben should not have been placed in the hostel, a converted Victorian house in Harrogate intended for adults aged over 25, which was clearly unsuitable for his needs and plagued with drug and alcohol abuse and outbreaks of violence.

He said local councils ought to have cast the net wider when searching for suitable accommodation. He will write to the Health Secretary to express concern over the lack of drug facilities for people aged under 18.

Outside the court, Ben’s parents expressed dismay at the outcome, saying the hearing had failed to provide the answers they sought. They claimed Ben had been ‘failed in death as he was in life’, and that his ‘life was seen as less valuable because he used drugs’.

However, during a moving four-hour interview, they told me the full story behind the tragically brief life of their ‘amazing’ son. It should serve as a warning to all middle-class parents who believe their children are beyond the reach of County Lines.

Outside the court, Ben’s parents expressed dismay at the outcome, saying the hearing had failed to provide the answers they sought. Pictured: Ben with his mother Kate

As Barry says: ‘We all have that unconscious bias, and assume, ‘Ah well, if there were drugs, he must have come from a family of druggies.’ The messages we want to get out, loud and clear, is that this can happen to any family on the social graph. Rich, poor, middle income, it doesn’t matter. If you’ve got a vulnerable child, or a child who is susceptible, and they start taking drugs and get into a bit of debt, this can happen to you. We never thought it would happen to us.’

Kate interjects: ‘We were so close. It’s terrifying how they can twist your child’s mind and undermine a relationship that you thought was absolutely solid. It is like brainwashing.’

‘It is brainwashing,’ says Barry. ‘That’s what grooming is.’

Listening to Kate and Barry, as they relive the afternoon when they found Ben in the hostel, is harrowing beyond words.

Having arranged to collect him for a psychiatric appointment, his mother arrived to find the door to his digs locked from the inside. Summoning the strength to break the lock, she found him lying, fully clothed, on the bed.

She remembers trying to revive him with CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) before collapsing in despair and exhaustion.

Kate had phoned Ben’s father, and the call remained connected. ‘All I could hear was Kate screaming, because she hadn’t realised her Bluetooth headset was in her back pocket,’ he told me bleakly. ‘I knew, as soon as I heard her, that Ben was dead.

‘It’s a sound you can never get out of your head. I was banging my fists on the steering wheel and shouting as I drove to the hostel.

‘But Kate had it much worse than me because she found him. Along with the grief, we relive that trauma every single day.’

Ben’s story begins in Irvine, Ayrshire, where he was born, on July 15, 2003. His parents met at Glasgow University, where Kate read classics and English, while Barry — a mature student ten years her senior — graduated in psychology and history.

‘He had a lovely early childhood,’ recalls his father. Smiling briefly, he remembers the day a family friend, who performed equine acrobatics, brought her horse to the farm, and allowed Ben a ride.

‘At one point the horse bucked, and Ben just held on. He was going ‘Woo-hoo!’ He courted danger all his life, but [then] it was in a good way.’

When Ben was four, the family, by then including a younger brother, moved to Knaresborough, North Yorkshire, to be nearer to Kate’s relatives. The symptoms of Ben’s illness first surfaced after he started school. An ‘incredibly gifted storyteller’, Kate says he would lose his train of thought when doing written work and found it difficult to sit still.

By the age of eight he was ‘having massive meltdowns’. He would bang his head on the walls and scratch his hands with a compass, and he heard voices.

His parents had suspected he was suffering from ADHD but claim that his school advised against having him diagnosed since it wouldn’t get him extra support and was just ‘a get-out-of-jail-free card’.

Powerful message: Ben’s grieving parents Barry and Kate after the inquest with a treasured photo of their beloved son

Matters worsened when he went to secondary school. He struggled with basic organisational tasks and often got into trouble. Then, when he was 12, they smelt cannabis on his clothes. As with many children, he had been given or sold the drug while playing — supposedly safely — in a nearby park.

His parents tried to stop his cannabis use immediately, talking to him about the dangers and, when that failed, taking a harder line. However, Ben was maturing into a big, powerful boy (he would grow to 6 ft 1 in) and it proved almost impossible to discipline him.

He would fly into terrifying, uncontrollable rages, smashing furniture, windows — anything within reach — and harming himself. Cannabis was worsening his anxiety yet, ironically, he said he smoked ‘weed’ for its supposed calming effect.

At 13, his school behaviour became so bad that he was sent to a Pupil Referral Unit for a term. There, his ADHD was finally recognised. He was prescribed with Ritalin, which helped him to concentrate but made him feel detached, as though he was ‘in a goldfish bowl’.

He was warned that, taken with cannabis, it could cause psychosis. Ben was 15 when he became embroiled in the County Lines gang, who insidiously supplied him with drugs, then forced him to sell for them when he couldn’t pay his debts. His parents don’t know how it happened, but they have since learned more about the people who took control of him, and Barry describes them as ‘a very serious bunch’.

By then, Ben had been excluded from school, and though he attended college one day a week and did work experience, had ample time for loitering with the wrong company. ‘I think these gangs have a scattergun approach. They try to get as many kids interested in drugs as they can,’ says Kate. ‘One of the things I’d advise parents to know, and discuss with their children, is that grooming doesn’t necessarily look the way you think it does.

‘Ben didn’t suddenly have new trainers and lots of money. It was more about getting him hooked, building up his debts, then putting pressure on him — a clever mixture of being friends and making him feel like he belonged to something, then threatening him.’

As Ben graduated from cannabis to harder drugs, such as cocaine and ecstasy, the amounts he owed to the pushers grew out of control. He lived in a constant state of angst, worsened by the drug-taking and psychological disorder.

Understandably, Kate and Barry wanted to protect him and gave him thousands of pounds to appease the gang. They now regret this, realising that, in the gang’s eyes, their willingness to settle Ben’s dues made him a more worthwhile ‘client’.

‘It’s very easy to say don’t pay the drug debts, but when your child is telling you that someone is going to batter them or cut their finger off, and beside themselves with fear, it’s very difficult to send them out of the house without giving them the money,’ says Barry.

His parents tried to stop his cannabis use immediately, talking to him about the dangers and, when that failed, taking a harder line

‘But sometimes you don’t even know whether you are being played. Is he saying he needs the money, but spending it on more drugs? It was a horrendously stressful time.’

When he asked Ben why drugs were easily available in a seemingly secure backwater such as Knaresborough, his son laughed: ‘Dad, don’t be naive. You can get them on Snapchat.’

He then clicked on the social media app and showed his father a video depicting a table laden with bags of cannabis and cocaine and a thick wedge of banknotes, the seductive message being that drugs were cool and selling them could make you rich.

The site also gave users the chance to place orders and fix meeting points for the handover. By the next day this ad would have vanished, to be replaced by a new account, yet the pushers always knew which young people to target.

Ben’s phone would ping with such messages all day and night, says Kate — another warning sign for parents.

The final stage of his exploitation came when shadowy County Lines overlords enrolled him as a dealer.

Strange cars would wait for him near his house; he was given a special ‘business’ phone that was taken off him at night. He had been well and truly ‘sucked in’, as Barry puts it.

Just how deeply became clear in the autumn of 2019. Before then, he had committed relatively minor offences — he was regularly caught shoplifting to pay for his habit and he was taken in for questioning on 26 occasions.

But now he was among County Lines operatives arrested for selling ‘wraps’ of heroin and crack, in York, more than 20 miles from his hometown.

During the subsequent interview, bosses of the drugs ring sent an underling to the police station posing as Ben’s ‘older brother’. His mission was to ensure that Ben was represented by their own trusted solicitor, who would ensure that he didn’t snitch.

Since the police knew Ben didn’t have an older brother, the ploy failed, but he was sufficiently scared to maintain his silence. It was a measure of the gang’s power and tentacle-like reach.

Ben was not charged. Instead, he was recognised as a victim of ‘modern slavery’ and his case was investigated under the National Referral Mechanism, a Home Office framework designed to provide support.

However, Ben’s parents claim he was failed badly by various agencies assigned to help him, including the social services and the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS).

At the inquest these organisations insisted they had done all they could for him, given their resources. However, Barry describes them as ‘worse than useless’.

They claim CAMHS played down their concerns over Ben’s mental health, even towards the end of his life, when he had a permanently self-inflicted black eye and would punch the walls so hard that he injured his hand beyond repair.

During his final months, Ben was a tormented soul. He complained of seeing snakes slithering from his bedroom wall and felt the urge to batter someone to death with a hockey stick. He went to A&E three times, pleading in vain to be committed to a psychiatric hospital. To no avail.

Ben’s mother Kate Roux (pictured with her husband, Barry Nelson) said the family had been ‘deprived of any answers’ about the cause of his death

At the inquest, a CAMHS psychiatrist claimed a ‘robust’, multi-agency care plan had been put in place for Ben’s welfare. His parents claim this is untrue.

In January 2020, while living in his mother’s annexe (which he routinely vandalised), Ben claimed the gang were about to ‘traffic’ him permanently to another city, where they would put him to work.

As he tearfully began packing his bag, Kate, frantic with worry, called the police. It was an understandable decision, but one she rues. Within minutes, officers stormed the house, pepper-spraying Ben and dragging him away.

Fatefully, he was placed, without supervision, in the social services hostel Cavendish House.

Less than a month before his death, the inquest heard, someone was stabbed there, and Ben was assaulted.

Margarita Gibson, Harrogate council’s housing needs manager, told the hearing that she and colleagues had searched in vain for more suitable accommodation, locally and in North Yorkshire’s six other boroughs.

Coroner Mr Heath said he could not say, ‘on the balance of probabilities’ that the placement had contributed to Ben’s death.

However, the hostel’s former warden said he was the youngest person she had known to be housed there, and his parents say his County Lines handlers must have rubbed their hands with glee when they discovered where he was living.

‘It was an absolute gift,’ Kate says, shaking her head. Barry nods: ‘These people are known to hang around places like children’s centres and homeless hostels.’

Ironically, visits from family members were banned, so Kate would meet him outside to deliver groceries and prepared meals.

On April 7, 2020, he texted her to say he was obsessing again about self-mutilation. When she phoned CAMHS, she says, she was met with platitudes, so she arranged for him to see a London psychiatrist privately via video-link. She told Ben he could use her laptop and afterwards they would have a picnic in the park.

He sounded relieved, but when she arrived to collect him, he failed to answer the door, and after forcing it open, she found him.

His parents hope that by telling Ben’s story they might spare the agony of other ordinary families from County Lines, with their ‘special kind of evil’.

The gang that entrapped their son remain free, however. Even now, they are doubtless targeting another vulnerable boy like Ben.

Source: Read Full Article