In his new documentary film Slava Ukraini, Bernard-Henri Lévy, France’s most famous public intellectual, dodges Russian sniper fire in Ukraine, nonchalantly wearing a khaki bulletproof vest over a chic bespoke suit.

He climbs onto a Ukrainian naval vessel in Odessa that is sweeping the Black Sea for Russian mines, his mane of greying hair blowing gently in the wind. And he surveys blown-out apartment blocks in Kyiv, descends into trenches with Ukrainian soldiers in Sloviansk and comforts a mother whose young son is so traumatised by war that he has stopped speaking.

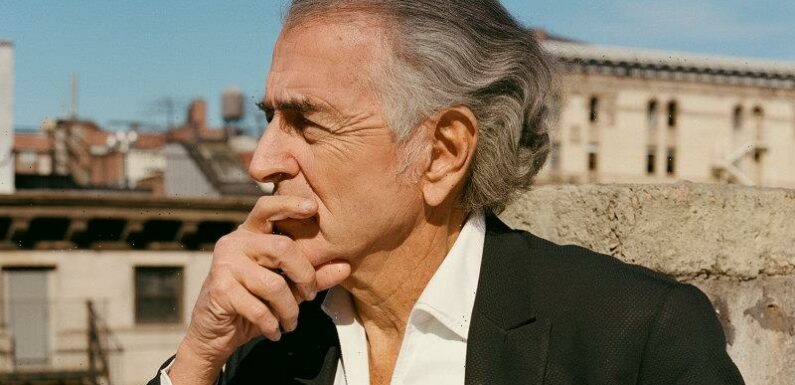

The writer and filmmaker Bernard Henri-Lévy.Credit:Clement Pascal/The New York Times

It can be easy to dismiss Lévy — and plenty do — as a 74-year-old reckless war tourist, an heir to a timber fortune playing action hero as Russian missiles rain down on Kyiv, Kharkiv and Mariupol.

But instead of spending the past year in his art-filled home on Paris’ right bank or enjoying retirement at his 18th-century palace in Marrakech, Morocco, Lévy has been braving Russian military assaults, vertigo and what he calls his natural tendency for melancholy to make his Ukraine film.

It was, he said, a necessary cri de coeur to support Ukraine in a conflict he views as nothing less than a battle for the future of Europe, global liberalism and Western civilisation.

“In Ukraine, I had the feeling for the first time that the world I knew, the world in which I grew up, the world that I want to leave to my children and grandchildren, might collapse,” he said during an interview at the Carlyle Hotel in New York in February, in which he peppered his accented but fluent English with allusions to Clausewitz, Hegel and Viennese literature.

A fight for liberal values: Ukrainian military medics treat their wounded comrade at the field hospital near Bakhmut, Ukraine last month.Credit:AP

A philosopher, writer, television personality and filmmaker, Lévy is a quintessentially French invention in a country that fetes its public intellectuals like pop stars. He is so ubiquitous in France that he is known simply as BHL, his initials akin to a French luxury brand.

But he is also a deeply polarising character, mocked by some critics as a dilettante or a sound bite philosopher.

But Lévy appears aloof from the criticism, viewing his work as a higher calling.

“The moral call never goes silent for me,” Lévy said. “I suppose at one point, I will no longer have the force to reply to the call.”

Slava Ukraini— “Glory to Ukraine”— premiered in France on February 22. It was shot over the past year during more than 10 trips Lévy made to Ukraine. The film (Lévy’s second about the conflict there) has garnered praise for its unflinching portrayal of the horrors of war.

“Without a doubt, Lévy has never filmed and conveyed distress and death with such harshness and such relentless rawness,” observed L’Express, an influential French magazine.

Lévy has spent the past five decades pleading with the West to intervene in seemingly intractable conflicts, inserting himself into battlefields in places like Bosnia, Darfur, Rwanda, Kurdistan, Afghanistan and Libya.

This time, however, he said the stakes were far graver. If President Vladimir Putin of Russia weren’t stopped, he warned, there would be a new Cold War, with Russia, Iran, China, Turkey and Islamic militants menacing the world and nuclear despots empowered to blackmail the West.

Those in the US Congress and European capitals who complain that arming Ukraine is too expensive, he said, are quite simply “morons”.

And why does he wear designer suits in a war zone? “Dressing is not important but it is one of the little signs of respect” to the people of Ukraine, Lévy explained.

Born in French Algeria in 1948 to a Sephardic Jewish family, Lévy burst onto the national stage in France in the 1970s, a young, long-haired philosopher railing against the perils of Marxism on the French left. He has written dozens of books, covering politics, philosophy, Judaism and American identity. He was a co-founder of an influential anti-racism group, and he became a media darling who had the ear of French presidents.

Yet he continues to attract opprobrium. He has been castigated for his outspoken support of Roman Polanski and Dominique Strauss-Kahn, both accused of sexually abusing women. He has been ambushed at least eight times by a Belgian pie-thrower who targets pompous personages, and he is the subject of no fewer than four sometimes-scathing biographies.

Inspired by Ernest Hemingway, photographed in Madrid during the Spanish Civil War.Credit:Granger Historical Picture Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Jade Lindgaard, a French journalist and a co-author of The Impostor: BHL in Wonderland, a critical investigation of Lévy and his work, argued that Lévy’s influence had waned, in part because he was out of touch with contemporary issues, like climate change and the #MeToo movement.

“To me, he has lost his credibility, probably because of all the mistakes he has made in his writings,” she wrote in an email, adding that his personal style undermined him.

But his defenders write off the attacks as little more than jealousy over his wealth, power and success. (He is married to the actress and singer Arielle Dombasle.) He is, they say, a man seeking to make and shape history, not just write about it.

“These people who criticise him are armchair intellectuals who never leave their Parisian salons,” said Marc Roussel, who directed Slava Ukraini with Lévy.

While Lévy is closely associated with France, he said his two towering role models were Ernest Hemingway, the physically imposing man of action who covered the Spanish Civil War, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, king of the gin-fuelled Jazz Age of Paris in the 1920s.

“I like to think with my feet, my hands, my lungs, my flesh,” Lévy said.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Get a note directly from our foreign correspondents on what’s making headlines around the world. Sign up for the weekly What in the World newsletter here.

Most Viewed in World

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article