Cardinal George Pell was not used to decisions going against him.

On a sunny afternoon in December 2018, the ambitious cleric who started in Ballarat and climbed almost to the top of the Catholic Church was powerless to prevent 12 everyday Victorians sending him to prison.

As the foreman of the County Court jury said the word “guilty” five times, Pell dropped his head and stared at the wood paneling in front of him.

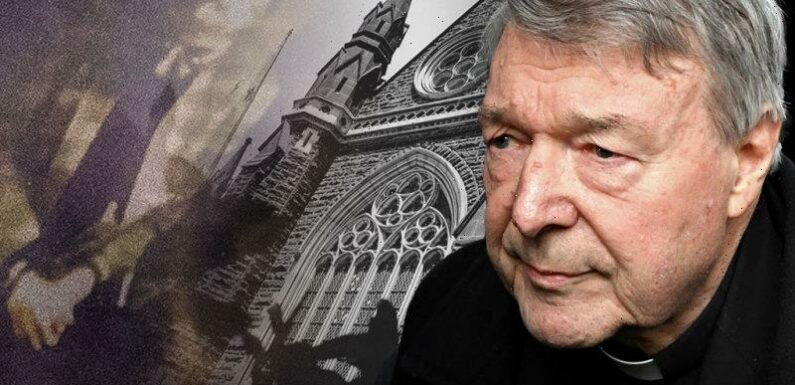

Cardinal George Pell was found guilty of child sex abuse in February 2019.Credit:Eddie Jim

But as the verdict reverberated around the room, the Cardinal and almost everyone else sat frozen in silence. Chief judge Peter Kidd retained a neutral expression. The lawyers at the bar table dared not look at each other.

The only noise aside from furious Biro strokes on reporters’ notepads was a woman’s repeated gasps. She was in court as a broad supporter of abuse victims, but couldn’t curtail her shock that a man of Pell’s position could be found guilty. A security guard took a couple of quick strides and crouched beside her – not to check her welfare, but to urge her to be quiet.

For a man of such power and prestige, the verdict was kryptonite. After the jury left the room, Pell struggled to stand in the dock and when the judge left the bench, the prince of the church looked every bit a frail, old man, fearful at what the future held. Kidd had wanted to remand him as a jail term was inevitable, but defence barrister Robert Richter successfully argued for bail as Pell was due to undergo knee surgery.

Pell was a conservative Catholic who had not said anything publicly for months; Richter was a Jewish social libertarian whose linguistic flourishes had failed to convince the jury of his client’s innocence. After the verdict, the two men held hands to comfort each other, both seemingly in disbelief.

It was seismic news that had to stay a secret. A suppression order that prevented the media from reporting Pell’s guilt was in place at the time, and wouldn’t be lifted until late February the following year. But throughout 2018, Pell’s court case was widely known within legal, media, political and religious circles.

Pell’s convictions were eventually overturned in 2020, when the High Court unanimously ruled in his favour and he was released after more than 400 days of imprisonment.

Pell was a daily visitor at the County Court for months throughout 2018, first in a trial that resulted in a hung jury and no verdict, and the subsequent retrial, where he was found guilty. Every day, a large white car dropped him and one of his solicitors at the corner of Lonsdale and William streets, and a protective security officer escorted them to the building’s entrance.

Some days Pell was just another figure, a tall man in a black suit among all the other grey-haired men in long black robes. On other days, passers-by did double takes. But because of the suppression order, Pell’s presence was a momentary curio, unlike Borce Ristevski and James Gargasoulas, whose cases were reported daily across William Street, at the Supreme Court, and whose appearances brought a gaggle of photographers, reporters and camera crews.

Inside the County Court, Pell had a small entourage everywhere he went. He nodded to security staff who ushered him past the entrance, and to those who opened doors. During breaks in court times, he sat in a small room with the door closed, usually with his friend and assistant Katrina Lee, and a member of his legal team. Over sandwiches they would discuss the case, but sometimes Pell played cards for a break. One day he strolled up and down the corridor outside the courtroom, stretching his long legs, until he realised reporters were watching, and he went back into the meeting room.

Pell’s trial attracted groups of onlookers, all with competing interests. A group of loyal churchgoers sat in court every day, and on the other side of the room there were a handful of advocates for victims of clerical abuse, a quiet truce between the two sides. Barristers with no connection to the case made time to come in and watch, and a couple of off-duty judges unobtrusively took chairs in the back row. Richter’s standing as the city’s pre-eminent defence barrister was a bonus for the legally interested.

Tim Fischer, previously Australia’s deputy prime minister and a one-time ambassador to the Holy See, attended to support Pell, and shook hands with him after the verdict. Fischer at least waited until the jury left the room before he approached Pell; unlike one witness, who offered his hand to the cardinal after giving his evidence, in full sight of the jury, which angered the judge.

Cardinal George Pell leaves the County Court in 2018.Credit:Simon Schluter

When the suppression order was lifted, news of Pell’s guilt brought a tidal wave of fury. In February 2019, when Pell returned to court for a pre-sentence hearing, hordes of protesters screamed abuse at him outside the court, held back by protective service officers and police. Far from the figure who was able to whip in and out of the court building in months earlier, people screamed at Pell to “rot in hell” and the sheer volume of antipathy meant it took Pell several minutes to make his way from car on the kerb to the building’s entrance. By that stage, he knew jail was inevitable and the verbal abuse had no visible effect on him.

In March 2019, when Kidd imposed the six-year sentence, Pell bowed to the judge and walked out in the custody of the guards. The packed courtroom didn’t see a skerrick of emotion. Outside, in the shade of the plane trees, crowds broke into applause.

Like all Victorian cases involving allegations of sexual crimes, Pell’s trial was closed to the public and media when his accuser gave evidence. By 2018, the complainant was a man in his 30s, and he alleged that he and his friend, then both teenage choirboys, were sexually abused by Pell in the mid-1990s in St Patrick’s Cathedral. The complainant also gave evidence on behalf of his friend, who died as a man from an accidental heroin overdose, having never made allegations against Pell.

Many observers privately conceded they didn’t hear evidence strong enough to convict Pell: there were no eyewitnesses and the circumstances appeared implausible. The jury, however, was clearly convinced by the strength of the evidence of one man: the complainant. In 2019, the Victorian Court of Appeal also found enough in the complainant’s evidence to uphold Pell’s conviction, albeit on a 2-1 majority. But Pell’s convictions were overturned in 2020, when seven High Court justices unanimously ruled in his favour.

Released from prison, Pell’s car was followed along the Hume Freeway by media crews and he was filmed at a service station. Within months, the royal commission released damning findings of Pell’s inaction about his knowledge of paedophile priests and the abuse of children in Victoria. He returned to the Vatican, where he found relative calm, away from the condemnation in his homeland.

Pell was Australia’s highest-ranking Catholic and his loss be mourned by millions. But also, his death will rekindle painful memories of their dealings with him. As archbishop of Melbourne in the 1990s, he was the architect of the Melbourne Response, the controversial compensation scheme that initially capped payments of $50,000. His preparedness to play hardball with some claims, and be legally aggressive when defending other claims as archbishop of Sydney is estimated to have saved the church many millions of dollars. The blind eye Pell turned against paedophile priests in his flock devastated countless young lives.

Like that invisible barrier in the courtroom during Pell’s trial, the effect of the cardinal’s death depends on where you sit.

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article