The worst megadrought in 1,200 years continues to burden the American West, and it’s forcing farmers to make tough decisions about their crops.

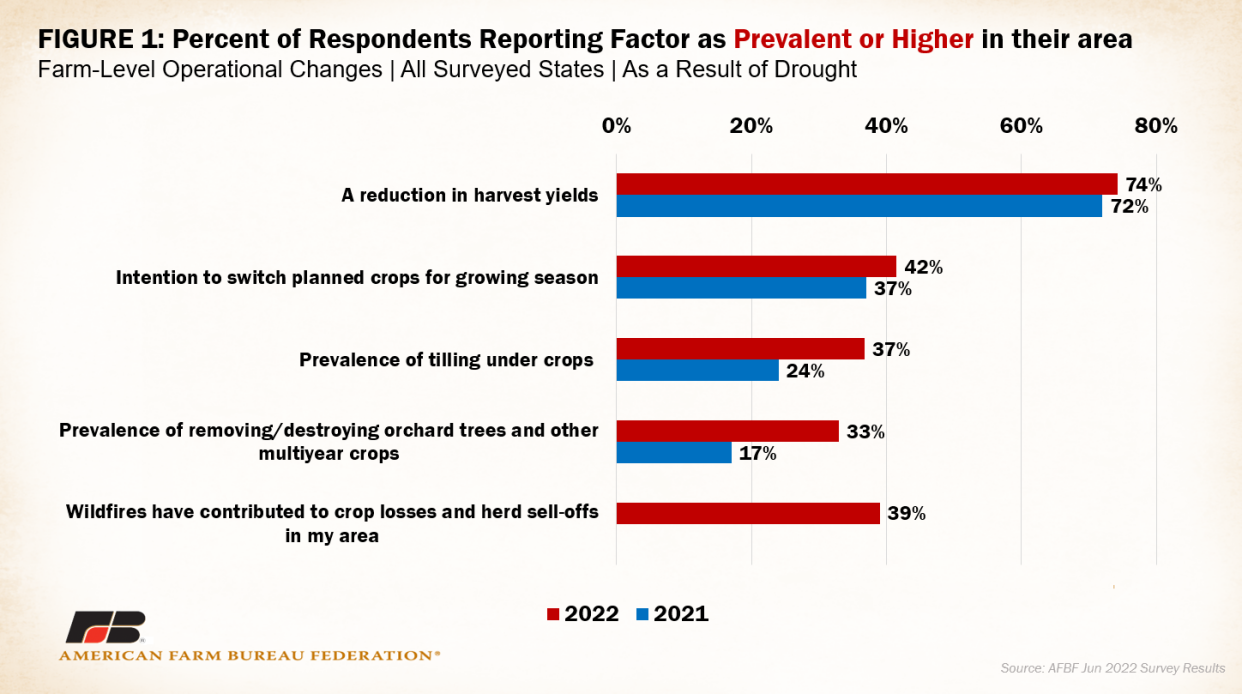

A new survey from the American Farm Bureau Federation asked farmers, ranchers, and Farm Bureau staff in drought-stricken areas about changes they’ve made to operations. Of the 652 respondents, around three-quarters said they saw yields decline due to drought, and a third reported destroying crops because of the extreme dry conditions, up from 17% last year.

“Depending on the size of the operation, farmers are handling this all sorts of different ways,” Daniel Munch, an economist at the American Farm Bureau Federation, told Yahoo Finance Live (video above). “On one end, you have smaller producers who can’t really absorb these changes. And they don’t really have the finances to invest and change. So… unfortunately, we’re losing those smaller farms.”

As of August 23, roughly half of the continental United States and two-thirds of the American West are experiencing drought. States like California, Nevada, and Utah are fully enveloped in drought as dry conditions sap the soil and vital water sources.

One critical river — the Colorado — is in such a state of jeopardy that the Bureau of Reclamation has stepped in to cut water deliveries to Arizona by 21%, Nevada by 8%, and Mexico by 7% after states failed to reach an agreement on reducing water use. The Colorado river supplies water to 40 million people and is a bedrock for the agricultural industry in the West.

That’s leaving many farmers to watch their businesses shrivel, although the effects of water cuts and changing conditions vary from farm to farm.

“Some of the larger farms, which can absorb the changes, they might be able to invest in other states — although, usually different climates are not conducive to growing orchards in other states,” Munch said. “Some places are investing in other countries.”

Drought stress

Currently, half of the production area in the U.S. for cotton crops is experiencing drought, as is 43% of rice producing areas, 78% of sorghum, and 53% of winter wheat, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Specialty crops like nuts, fruit trees, and herbs face significant financial risks due to their higher water demand and overall value.

“Cotton has been absolutely decimated,” Michael Magdovitz, senior commodities analyst at Rabobank, told Yahoo Finance Live about how drought has affected that particular crop. “At the end of this next year, reserves in the U.S. of cotton stand to be at their lowest on record, which can impact the price of your shirt.”

As a result, Munch explained that farmers are choosing to destroy crops and kill cattle that won’t reach maturity due to the limited water supply.

In one instance reported by the American Farm Bureau Federation survey, a wine producer in California dropped five acres worth of Cabernet grapes, foreclosing any potential revenue for the current year.

“When we look at crops, many of our producers, 37%, have reported tilling under crops because of dry conditions,” Munch said, while “33% are removing orchard and other multiyear crops like vineyards because they just don’t have enough water.”

“Many of these multiyear crops are major investments,” he added. “They don’t start producing fruit for three to five years. So to make that decision to move a crop is a massive undertaking for future revenue.”

The issue also extends to livestock ranchers, as 57% of beef cattle and about half of all milk-producing cows are in drought-stricken areas. The dairy industry, in particular, has been hit by climate change as dairy cows are sensitive to heat stress which can lower milk quality.

“On the livestock side, just massive liquidation of the livestock herds because they don’t have enough water to support their herds,” Munch said. “People are going across state lines, driving 13, 14 hours to get hay at extremely exorbitant rates. So just major changes that farmers and ranchers are facing because of these dry conditions.”

Water ‘on everyone’s mind’

Drought stress is expected to drive food prices up for U.S. consumers, but the economic ramifications are even more far reaching for rural producers and regional economies.

In 2021 alone, drought cost the Golden State 8,745 jobs and $1.2 billion, with spillover effects more than doubling the jobs affected and bumping up the economic toll to $1.7 billion, according to a report prepared for the California Department of Food and Agriculture.

“Water is on everyone’s mind,” Lynne McBride, executive director at the California Farmers Union, told Yahoo Finance in March.

As rivers dry up and water deliveries are reduced, it has forced many producers to rely on groundwater. Despite efforts to keep groundwater withdrawals at sustainable levels, those reservoirs have also been depleted.

Beside the water scarcity concerns, overly depleted aquifers can cause the land to sink, posing a threat to infrastructure, and like a fragile sponge, as California hydrologist Tom Ballard said in a press briefing, they lose their capacity to retain water during times of replenishment.

The compounding factors in the West make water conservation a top priority, McBride explained, and producers have begun adopting micro irrigation, drip irrigation, and soil sensors to reduce their water intensity.

However, these changes require time and money, which not all producers have.

“Part of the challenge of being a farmer is that you don’t set your price,” McBride said. “You’re a price taker, not a price setter. And so when costs go up, including relating to water management systems like these, which are investments to reduce water use, there’s no way for farmers to pass that those costs along based on how our food system works.”

Sandy Dall’Erba, professor in the department of agricultural and consumer economics at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, told Yahoo Finance earlier this year that “all these options are being implemented but they take time.”

He added that in Spain, which is similarly dry and dependent on agriculture, “it took on average 20 years for farmers to shift from other types of irrigation to a low-flow (especially drip) irrigation system.”

“Furthermore,” Dall’Erba continued, “the question of where the funding would come from is not obvious. Farmers already pay very little for water in the Southwest; hence they do not have strong incentives to fund new irrigation systems themselves.”

Increasingly, that means state and federal programs are being called upon to help. California’s State Water Efficiency and Enhancement Program (SWEEP), for instance, provides grants to farmers to install water-saving technology. On the federal level, the Wildfire and Hurricane Indemnity Program-Plus (WHIP+) and the Emergency Relief Program aim to help producers cover crop losses, though Munch noted that, for the former, payments were late and, for the latter, there is uncertainty over whether it will be renewed for 2022.

Over the long term, scientists expect more funding will be required to adapt to climate change as higher temperatures exacerbate extreme weather events and drought.

In April, an analysis by the Office of Management and Budget found that by end of century, the government’s expenditures on crop insurance subsidies could increase anywhere from 3.5% to 22% due to climate change-related crop losses. That figure amounts to an additional cost to taxpayers of $330 million to $2.1 billion annually.

“If only local agricultural production in the Southwest were to serve local demand only, maybe the ecological impact would be less serious,” Dall’Erba said. “However, it is not the case. Focusing on the state of Arizona only, my work shows that crop production (lettuce, cotton, alfalfa, hay) consumes as much as 73% of all the water used in the state and 79% of that crop is exported to the rest of the nation and abroad. It corresponds to exporting 67% of the state’s water.”

Grace is an assistant editor for Yahoo Finance.

Read the latest news on the climate crisis from Yahoo Finance

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance

Download the Yahoo Finance app for Apple or Android

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, LinkedIn, and YouTube

Source: Read Full Article