By Tony Wright

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

In the year 1937, William Cooper, an Indigenous man with a snowy moustache and a steady gaze, sent a petition to the Australian parliament, requesting that it be forwarded to the King.

It asked, among other things, for a representative to be appointed to parliament to speak for the interests of Australia’s Aboriginal people.

It was a simple request for an Indigenous voice to parliament, if less refined than today’s “Voice” proposal.

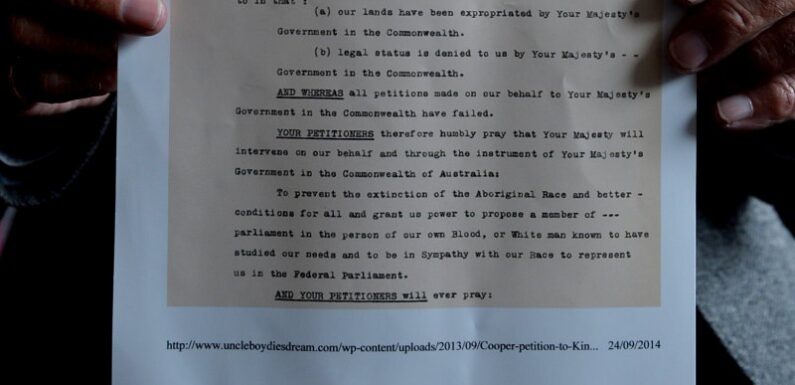

Uncle Boydie Turner with a copy of the petition originally written by his grandfather William Cooper for Aboriginal representation in parliament.Credit: Justin McManus

Many Australians appear to believe the idea of an Indigenous Voice to parliament is a relatively new and even exotic request from Aboriginal people.

In fact, Cooper’s petition of 87 years ago was merely the first of a number of formal approaches over many decades. Each was rebuffed in one way or another.

Cooper’s petition got no further than the cabinet of then-prime minister Joseph Lyons’ conservative government.

“It is not seen that any good purpose would be gained by submitting the petition to His Majesty the King and it is recommended that no action be taken,” the cabinet concluded when the matter was finally considered in 1938.

The then-minister for the interior, John (later known as “Black Jack”) McEwen, signed off on its fate.

To add insult to injury, the government lost the original petition. The only formal archival record remaining in Australia is the cabinet paper describing and rejecting it.

It took until 2014 for one of Cooper’s descendants to produce a facsimile that was relayed to the late Queen Elizabeth II by then-governor-general Sir Peter Cosgrove. It sits in the Palace’s archives, a reminder of an old, lost campaign in a former British colony.

One of the reasons the cabinet decided against forwarding Cooper’s request to the King was because, under the Constitution of the time, the federal parliament did not have the power to make a law for Aboriginal representation in parliament.

As Australians agonise anew over whether Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders should get a formal Voice to parliament enshrined within the Constitution, it is worth remembering Cooper’s effort all those decades ago.

Cooper and his fellow activists in the Australian Aborigines’ League had spent years gathering the signatures of 1814 Aboriginal peoples from every state and territory except Tasmania.

The petition pointed out that the British government in 1788 had issued “a strict injunction … to those who came to people Australia, that the original occupants and we their heirs and successors should be adequately cared for”.

But the terms of the commission had not been adhered to, the petition declared, because:

“(a) Our lands have been expropriated by Your Majesty’s Government in the Commonwealth, and

(b) Legal status is denied to us by Your Majesty’s Government in the Commonwealth.”

Cooper knew keenly both of these truths.

He was born on Yorta Yorta country near the intersection of the Murray and Goulburn rivers, a bit upstream from where Echuca now sits, in either 1860 or 1861. He wrote in a letter in 1887, that “as a lad, I can remember 500 men of my tribe, the Moiras, gathered on one occasion. Now my family is the only relic of the tribe.”

His family had little choice but to move to the Maloga mission near Moama. Young Cooper had a few months of formal schooling before he began work on a station owned by a wealthy landowner, Victorian parliamentarian and for a time state premier, Sir John O’Shanassy. The property was known as the Moira run, named after Cooper’s own displaced clan.

Cooper later worked all over Queensland, South Australia, NSW and Victoria labouring, shearing, droving and horse-breaking, while also living at Maloga and nearby Cummeragunja missions.

He never lost his belief that justice and land should be delivered to his people. In 1887, he signed with other residents of the Maloga mission a petition calling for Aboriginal families to be granted small parcels of land so they could make their own living.

In 1933, aged in his 70s, he moved to Fitzroy in Melbourne so he could gain the old-age pension because Indigenous people on missions were ineligible.

There, he helped establish the Australian Aborigines’ League, campaigning for the repeal of discriminatory legislation and for programs to “uplift the aboriginal race”.

Part of this campaign was the petition to the King. Despite obstruction from both state and federal governments, he and his team spent several years gathering the signatures of Aboriginal people, many of whom affixed their “mark”.

The cabinet document noted rather snootily that “According to the names [on the petition] it is reasonable to assume that many of the signatories are not full-blooded”.

The essential requests, according to the cabinet document, were:

“to prevent the extinction of the aboriginal race;

“to secure better conditions for all; and

“To afford aboriginal representation in the Federal Parliament, either by an aboriginal or a white person known to have studied the need of aboriginals and to be in sympathy with them.”

The last of these three requests was not simply to allow an Aboriginal person or sympathiser to be elected to represent an electorate like other MPs, but to allow what amounted to a voice in the parliament specifically related to Aboriginal concerns.

Cooper died in 1941. His cause was taken up by his nephew, Sir Douglas Nicholls, a Christian pastor, well-known Australian footballer and the founding treasurer of the Australian Aborigines’ League.

In 1949, Nicholls persuaded Kim Beazley Snr, a federal Labor MP in the Chifley government, to write to then-prime minister Ben Chifley to ask for Aboriginal representation in the parliament.

Beazley wrote that he’d explained to Nicholls that “by Section 51, sub-section 26 of the Constitution, the Commonwealth is forbidden to make laws for the people of aboriginal race, and have informed him that that may constitute a constitutional barrier to what he desires, and that in any case the value to his people of an aboriginal representative in a Parliament forbidden to legislate for aborigines would be limited”.

Beazley added, however, that Nicholls’ request “appears to me … to be completely just”.

He asked that Chifley consider legislating to allow Aboriginal representation in the parliament.

And he called for a referendum “to amend Section 51, sub-section 26, of the Constitution to eliminate the prohibition on the Commonwealth which forbids it to legislate for people of aboriginal race”.

Both requests fell on deaf ears.

In fact, a referendum had been held in 1944 that asked Australians to consider giving the Commonwealth the ability to legislate for Indigenous Australians. It was part of a 14-question referendum that was primarily designed to give the government the power to maintain wartime controls as Australia readjusted to peacetime conditions.

More than half a century after four young Aboriginal men planted a beach umbrella opposite Canberra’s Old Parliament House, the tent embassy remains.Credit: Alex Ellinghausen

The referendum was lost, including what appeared to be an afterthought concerning legislating for Aboriginal people.

Nevertheless, the campaign by Nicholls and the Australian Aborigines’ League continued, and in 1962 the Australian parliament legislated to give Indigenous peoples the right to vote in federal elections and to stand for election.

The 1967 referendum held by Harold Holt’s Coalition government and supported by the Labor Party finally amended section 51(xxvi) so that parliament could make laws for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. It was the most successful referendum in Australian history, with 90.77 per cent of Australians voting in favour of removing basic discrimination from the founding document.

On January 26, 1972, four young Aboriginal men – Michael Anderson, Billy Craigie, Bert Williams and Tony Coorey – made the point that the parliament was still not listening to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

They planted a beach umbrella opposite Canberra’s Old Parliament House, establishing Australia’s first Aboriginal tent embassy. More than half a century later, the embassy remains.

And the old dream of people like Cooper remained unfulfilled.

Today, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are still not recognised in the Constitution as the first Australians, and are still denied a formal voice to transmit their concerns to the parliament.

The long process that led to the Uluru Statement From the Heart was supposed to rectify that.

There were years of work by an expert panel on constitutional recognition of Indigenous Australians and an investigation by a joint select committee on constitutional recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

A Referendum Council was jointly appointed by then-prime minister Malcolm Turnbull and opposition leader Bill Shorten on December 7, 2015, to advise on how a successful referendum might be held to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Constitution.

Uluru, setting for the 2017 Statement from the Heart. Credit: Emilie Ristevski

The council chose the four principles established by the expert panel to guide its assessment of proposed models for constitutional recognition.

Each proposal had to contribute to a more unified and reconciled nation; be of benefit to and accord with the wishes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples; be capable of being supported by an overwhelming majority of Australians from across the political and social spectrums; and be technically and legally sound.

The council held a series of “dialogues” across the nation to give Indigenous communities the chance to have their say on whether, and how, they wanted to be recognised in the Constitution.

Finally, more than 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders met over four days in May, 2017, at the foot of Uluru in Central Australia to thrash out a consensus position.

The result was the Uluru Statement From the Heart.

It spoke of Indigenous Australians’ experience as the “torment of our powerlessness”.

“We seek constitutional reforms to empower our people and take a rightful place in our own country,” the statement declared.

“When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish. They will walk in two worlds and their culture will be a gift to their country.

“We call for the establishment of a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution.”

It ended with an invitation.

“In 1967 we were counted, in 2017 we seek to be heard. We leave base camp and start our trek across this vast country. We invite you to walk with us in a movement of the Australian people for a better future.”

Turnbull’s government refused the invitation, arguing the “Voice” would constitute a third chamber of parliament and had little chance of winning public support at a referendum.

Anthony Albanese at the Garma festival in August. “We can get this done together,” he said.Credit: Rhett Wyman

Labor’s Anthony Albanese, having won government in May 2022, promised the question would be put to a referendum.

Early support, however, began fracturing when Peter Dutton set his opposition against the proposal. Observers understood from that moment the referendum was in trouble – no referendum in Australia’s history has succeeded without bipartisan support.

Albanese reiterated there would be no backtracking when he attended the Garma festival in north-east Arnhem Land in August.

“We can get this done, together,” he said. “And we can get this done, now.

“Because if not us, who? And if not now, when?”

And so, Australia is deciding.

Cooper, we might imagine, would have understood the seemingly endless frustration in trying to persuade Australia to give its First Peoples a voice.

Cut through the noise of federal politics with news, views and expert analysis from Jacqueline Maley. Subscribers can sign up to our weekly Inside Politics newsletter here.

Most Viewed in Politics

Source: Read Full Article