DOMINIC LAWSON: Britain’s economic problems have little to do with Brexit (whatever the BBC’s viral videos might say)

You’ve heard it once, you’ve heard it a hundred times: the recent months of political chaos in the UK are the malign consequence of Brexit.

That is what the European Press have been saying — a point of view enthusiastically recycled in this country by those who have always found it impossible to come to terms with the result of the 2016 Referendum.

Only it isn’t true. The reason Boris Johnson was forced out of office by his own MPs was entirely down to his conduct in public office.

As for the astonishingly rapid meltdown of Liz Truss’s administration, this, too, had nothing to do with Brexit. It was, instead, the consequence of a disastrously improvident ‘mini-Budget’ that spooked the markets, combined with appalling political judgment.

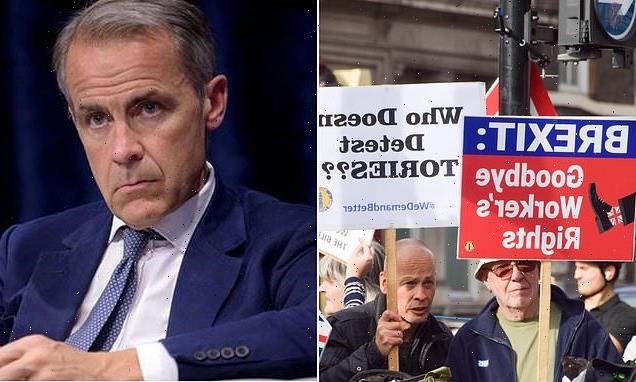

Former Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, gave an interview to the Financial Times a fortnight ago in which he claimed that ‘in 2016 the British economy was 90 per cent of Germany’s. Now it is less than 70 per cent’

But that debacle encouraged the former Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, to give an interview to the Financial Times a fortnight ago in which he claimed that ‘in 2016 the British economy was 90 per cent of Germany’s. Now it is less than 70 per cent’.

Promise

This went viral, and a week ago the former chief speechwriter for David Cameron, Clare Foges, repeated Carney’s claim, describing it as ‘a fact’.

She added that in 2016: ‘No one voted to leave the single market or the customs union.’ No one? Is that another ‘fact’?

In reality, the Leave campaign made it clear that one reason for exiting the EU was to be able to negotiate our own trade deals, which would be impossible if we remained within the customs union.

As for the single market, one of its non-negotiable elements is accepting ‘free movement’ of people within its borders. So it would also have been impossible to meet the Leave campaign’s promise to ‘end free movement’ if we had remained part of the EU single market.

It is because Sir Keir Starmer understands these simple points that he promised a Labour government would not rejoin either of those institutions. Unlike Ms Foges, he is under no illusions as to what the millions of Leave voters had been calling for — and he wants their votes at the next General Election.

But is Mark Carney right about the relative performance of the British and German economies since 2016? No, and that’s putting it politely.

Yes, the UK does have its economic problems, which have been apparent not just since 2016, but for far longer. They concern productivity, as much as anything. It’s true that Brexit in itself doesn’t address that: but nor would returning to the rules of the European Union. Sadly, however, blaming everything on Brexit is what gets some people up in the morning

Ashoka Mody, the author of Foreign Direct Investment And The World Economy, said last week that Carney’s claim was ‘complete bulls*** . . . if anything, the British economy has performed slightly better than the German since Brexit’.

And the eminent economist Jonathan Portes, who is absolutely no fan of Brexit, tweeted: ‘I see Clare Foges is repeating Mark Carney’s zombie statistic. For the umpteenth time, this is nonsense.’

When I contacted Professor Portes, he explained that Carney had arrived at his ‘zombie statistic’ by measuring the value of these two economies at prevailing exchange rates. But no respectable economist does this when assessing the relative health of economies over time. They use a measure known as purchasing power parity, which is the best way to compare real incomes and living standards in different economies.

As Portes put it to me: ‘The pound has risen by almost 10 per cent against the dollar since the Truss nadir. Has the UK economy really grown by almost 10 per cent relative to the U.S. in a few weeks?

‘Similarly, Carney is choosing a date when the pound was abnormally high against the euro (January 2016), another one when the pound was much lower, and then saying we’ve underperformed Germany by 20 per cent.

‘That’s just obvious complete nonsense. If you look at actual annual growth rate in domestic currency, the UK and Germany have grown by quite similar amounts since 2016.’

Collapsing

Portes still thinks Brexit is not beneficial for the economy, but is prepared to reassess the extent of that as events develop.

Carney, however, has a very large axe to grind. As Bank Governor at the time of the Referendum, he unwisely became a support act for Project Fear and issued forecasts suggesting that simply voting to leave the EU would cause unemployment to rise and both foreign direct investment and exports to fall.

None of these things happened, still less the Bank’s ‘worst case scenario’, which projected our gross domestic product falling by 8 per cent within a year and property prices collapsing by 30 per cent.

The reason Boris Johnson was forced out of office by his own MPs was entirely down to his conduct in public office

Mercifully, Carney, whom the BBC honoured as its Reith Lecturer in 2020, does not appear in a film about Brexit in a new series, Ros Atkins On The Week, presented by the BBC News’ analysis editor.

The first episode contained a five-minute near-monologue by Atkins under the title Brexit And The UK Economy. On its home page, the BBC describes the programme as ‘impartial’. Odd that it should need to say that. Isn’t all the Corporation’s output meant to be so?

I’m sure Atkins believes his Brexit And The UK Economy is entirely impartial, although it began with film of the Italian-American economist Mariana Mazzucato declaring that ‘Brexit was, is, and will be a total disaster’.

As the film develops, Atkins gives the starring role to figures from the Office for Budget Responsibility, which assert that by 2030 Brexit will reduce our GDP by 4 per cent below what it would have been had we stayed in the EU.

But as Julian Jessop, a former Treasury economist — one of the minority in his profession who supported Brexit — pointed out to me: ‘The OBR figure is just an assumption, which relies on guesswork about the impact of a reduction in trade intensity on long-term productivity.

As for the astonishingly rapid meltdown of Liz Truss’s administration, this, too, had nothing to do with Brexit. It was, instead, the consequence of a disastrously improvident ‘mini-Budget’ that spooked the markets, combined with appalling political judgment

‘Any serious analysis would also acknowledge the conflicting signals from the data, including that UK exports to the EU have moved broadly in line with those to the rest of the world.’

Jessop observes that, in the film, ‘there was no discussion of what has actually happened to GDP and inflation in the UK compared with our peers in the EU, perhaps because the differences have been small and this would not fit the narrative. The BBC report is sloppy and one-sided.’

Horror

Never mind, it has gone down a storm on the social media among those obsessed with getting the UK to rejoin the EU.

So one Twitter-user, known as Brexit Shambles, celebrated: ‘Last night the full horror of Brexit was expertly collated and presented by Ros Atkins … it’s an unmitigated disaster.’ Another fan declared: ‘A masterful, brilliant summary of the Brexit ****show by Ros Atkins.’

To be fair, Atkins’ own conclusion was much more moderate in tone. He ended his commentary with the words: ‘Brexit is one of the things constraining the growth of the UK economy.’

What this also leaves out is that for many millions of those who voted for Brexit, it was not just, or even at all, about GDP.

Nevertheless, the fact is — to use the phrase beloved of Brexit’s most implacable opponents — since the vote to leave and up until the end of the second quarter of this year, data from the authoritative Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) show that the cumulative growth rate of real GDP in Italy was 4 per cent, in Germany 5.5 per cent, in the UK 6.8 per cent, and in France 7.6 per cent.

But, again, you won’t find any reference to those figures — real ones, not assumptions based on theoretical models — in the BBC’s supposedly definitive report.

Yes, the UK does have its economic problems, which have been apparent not just since 2016, but for far longer. They concern productivity, as much as anything. It’s true that Brexit in itself doesn’t address that: but nor would returning to the rules of the European Union.

Sadly, however, blaming everything on Brexit is what gets some people up in the morning.

Source: Read Full Article