Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

Imagine you have a bag of marbles – nine red, 10 blue, four yellow. Now draw one out. What are the odds off that marble being blue? Keep it, and pluck out another. What’s the likeliest colour pairing?

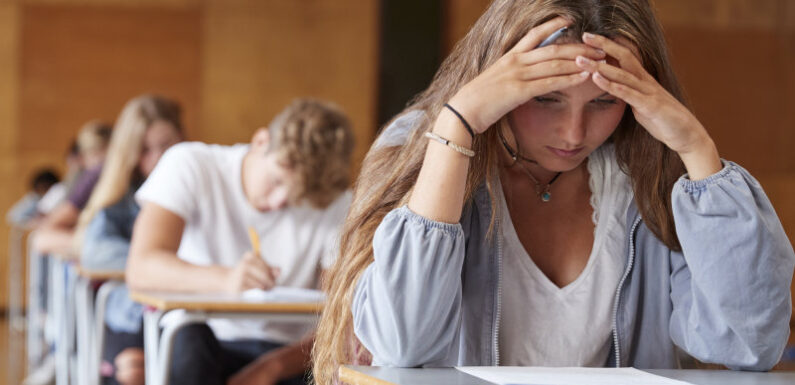

An age ago, when I did year 12, that sort of question typified basic maths. Odds and algebra. Marbles and triangles. Stephen Hawking would hardly break a sweat, but I did. Hence my empathy for students trying to keep their nerve, and ATAR projection, locked in battle with each paper. The swotting, the sweating, and then zero hour. Bang. Go. Prove yourself!

Should heads roll over last week’s VCE maths exam errors?Credit: iStock

Exams are tough enough. Add a typo to the equation, a misplaced number, a redundant word, and your marbles start rolling. Last week, the VCE Maths Method 2 fluffed a tennis ball question. A lower-case m should have read as metres. Thankfully, the slip was flagged before the clock began. Still, imagine 15,000 lurching stomachs, as one tennis fault made students dread others being served.

Metre-gate wasn’t the only hair in the soup. Three bloopers struck in one week, across one discipline, from an incorrect figure embedded in a matrix to a logic challenge where “the maximum decrease in time of any of activity is two days”. Did you spot the blue? Yes, a surplus “of”, which most students would either overlook, or accept as flawed.

Just as shrewder readers may have detected my wayward “off” in the first paragraph. Either way, you’ve reached this far. Yet errors have a nasty habit of multiplying misgivings in any reader, as maths geek Adam Spencer explained when we chatted on air.

“If an English paper used ‘discuss’, leaving off the last s, then nobody’s thinking ‘discus’. We’re not talking the Olympics. It’s clearly just a misprint and we go on. In maths, however, similar to cryptic crosswords, the precision is vital. Omit a single minus sign from a question, and you render it meaningless. So the bar is raised in some ways.”

The pressure too, on examiners as much as examinees. Book editors know the burden well. Or Chilean mint directors, like Gregorio Iniguez, who authorised 1.5 million coins into circulation in 2008, before noticing their message: REPUBLICA DE CHIIE. Tails were kicked. Heads rolled.

Should the latest exam saga prompt similar consequences? What are the odds? The likely bet is a public call for greater scrutiny. Though more eyes are no guarantee – just ask Lonely Planet, who published their 2010 guide to “WESTEN EUROPE”, despite the countless checks, everyone missing the truant 72-point R on the spine.

Accuracy is crucial in times of anxiety. Unscathed, tourists can continue to roam “Westen Europe”, unlike year 12 students who shouldn’t need to grapple with a stray robot appearing in Nikolai Kochergin’s famous artwork Storming the Winter Palace, as happened in 2012, as part of the VCE History: Revolutions exam. Transformers v the Tsar?

Ditto for HSC students in 2010, finding a bungled alphabet in the multiple-choice section of their Business Studies paper. Somehow ABCD appeared as ACBD. Similar but different. Under pressure, if basic maths taught me anything, it’s that one doubt can trigger a domino-like collapse of the entire box and dice.

“All through high school,” as Spencer reminds us, “you’re told if you can’t work the question out, you’ve got to work harder. It’s all there, and you’re the one not getting it right. So think more. Think more. Think more.” That mantra applies to all of us.

To read more from Spectrum, visit our page here.

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from books editor Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.

Most Viewed in Culture

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article