Holed up at the Last Chance Reformatory School for “very disturbed young men”, Shy does his best to lie low. Just him, his mixtapes and his rucksack. But that’s not so easy when there’s a bunch of do-gooder teachers talking him through those infernal behaviour maps, or a television crew sticking their cameras in his face for some documentary about Last Chance’s impending closure.

And now the other kids are turning on him, too; teasing him, stealing his things. So Shy is making a break for it, escaping into a haunted night filled with voices and memories that clang in a cacophonous chorus: family, friends, girls, drugs. The punk whose face he sliced open with a broken bottle.

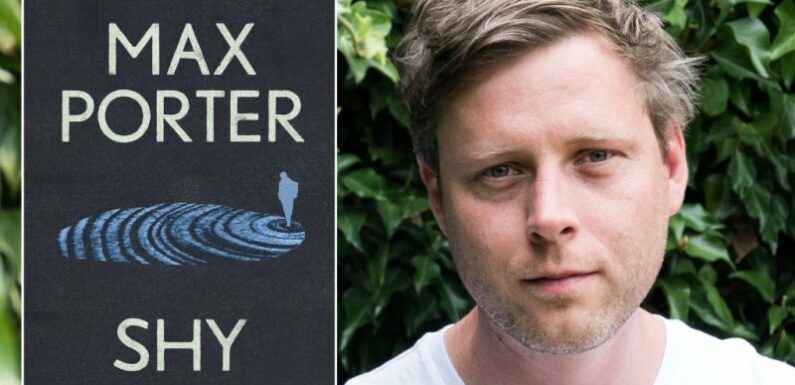

Max Porter revels in pop-cultural nostalgia in Shy.

Much like Max Porter’s previous books, Grief Is The Thing With Feathers and Lanny, Shy is an interrogation of fledgling masculinity cast through a lens of wildly kaleidoscopic experimentation. On a purely aesthetic level, it explodes like a Catherine wheel on the page. Bold passages here, fonts and sizes changed there, entire sentences running across double page spreads or even onto the reverse side on the page.

And yet, for all its joyful stylistic abandon, Shy is much more insular than its predecessors, contained both in time – the whole book takes place over the course of a few hours – and nature. Left alone with his thoughts, Shy is just a teenager trying to find some meaning in his messed-up life. How did he get here? Can he ever really get out? What future is there for someone who society has abandoned?

Credit:

There’s an obvious comparison to be made to Holden Caulfield, but it does Shy a disservice. Porter is not interested in simply creating a portrait of teenage anomie for the new era. He wants us to confront our own biases, to pick through the contents of our collective too-hard basket. To understand.

As Shy trudges through the English countryside, Porter allows the warring factions of his psyche to battle without judgment or heavy-handed intervention. His memories spark and sputter, with long stream of consciousness mumble-rap passages set against staccato bursts of rage and frustration. Somewhere in the cracks, there is hope, too.

It is a radical act of empathy, disorienting at first but, once you grasp the rhythm, exciting and insightful. It is also a rare case of accessible experimentation that welcomes the reader into its world and opens them to the workings of a fractured mind. Through Shy we catch glimpses of an entire social ecosystem that predates the mod-cons and hyper-medicalisation of today. His world seems almost anachronistic, stripped of mobile phones, streaming platforms, and routinised diagnoses.

Indeed, Porter revels in the pop-cultural nostalgia. Shy is heavily steeped in ’90s music, the prose often pulsating to a backbeat of drum and bass; a Portishead song of the damned. For the children of Last Chance, this unironic Ali G patois is, for all its posturing, sweet and funny, a source both of refuge and independence in an otherwise highly proscribed world. It is that world – of underfunded and under-resourced schools, over-eager law enforcement, and persistent systemic failure – for which Porter reserves his rage.

Notwithstanding its compassionate core, Shy bristles with righteous indignation at a country that has long failed its most vulnerable children and that, over the past 30 years, has done little to lift its game. For this, Shy is the perfect avatar, oblivious to the greater machinations dooming him to failure, whose true rebellion is found not in his acts of violence or defiance, but in his naïve commitment to Quixotic dreams. With all we know is stacked against him, it’s hard not to hope they come true.

Shy by Max Porter is published by Faber & Faber, $24.99.

Bram Presser is the author of The Book of Dirt (Text).

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from books editor Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.

Most Viewed in Culture

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article