Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

“The Voice is the clean canvas Australia needs to paint a better future,” says a key Yes campaigner. “All the No campaign is doing is throwing shit at it.”

Some of that shit is sticking, and by far the stickiest is the claim that the Voice is divisive, dividing Australians by race. Because the Voice would comprise only Indigenous Australians, advising only on matters that concern Indigenous Australians. In a society that holds equality as its highest ideal, this line of attack is devastating.

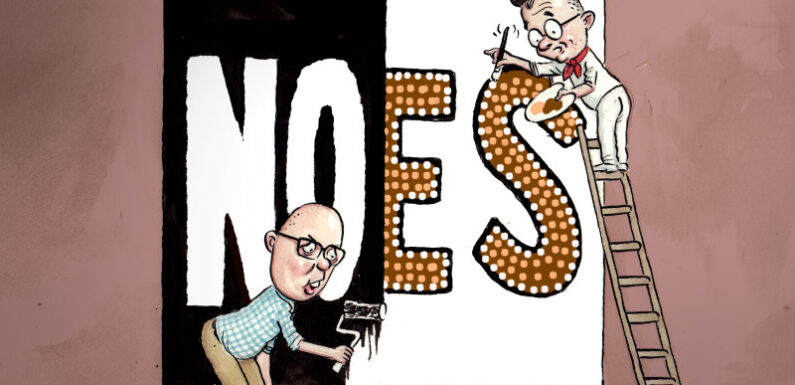

Illustration: John Shakespeare. Credit:

Peter Dutton has argued that the Voice would “permanently divide us by race” and “re-racialise” Australia. It’s a simple idea, a striking claim, a respectable argument. Surely, if one race is to get its own Voice, others should too, and we should have multiple Voices? Or we should keep the country unified and have none, which is, of course, the No campaign’s contention.

Senior figures in both the Yes campaign and the federal government agree that this claim of racial division is the most effective argument against the Voice. It has been devastating for Yes. And, so far, it has gone unanswered by the Yes campaign. The Yes campaign has simply talked past the claim.

What is the answer? The core truth is that the Voice is not about race. It’s about indigeneity. What’s the difference? Race is about skin colour. Indigeneity is about first peoples. Australia is home to various races but has only one first people.

As Noel Pearson has said in years past: “If we were in Lapland, we would be blond and blue-eyed and we’d still be Indigenous.”

Noel Pearson says Indigenous people are used to being underdogs.Credit: Rhett Wyman

And the indigenous people of Lapland, the Sami people living in the northernmost realms of Finland, Norway, Sweden and Russia, suffered a similar experience of dispossession at the hands of Scandinavian settlers, as my colleague Rob Harris wrote this week.

“Who would say to the Sami of the Arctic Circle or the Maori of New Zealand that their status is based on race and not that they are native to their homelands?” Pearson said at the 2019 Garma Festival.

It’s easy to conflate race and indigeneity. So while it may be “shit”, it’s clever shit. Because the difference is profound yet can appear subtle. It’s also a “rancid dishonesty”, according to Pearson. But why is it important to distinguish between the two? Simple. Indigenous Australians suffered uniquely. So they deserve unique redress. Hence the Voice.

Their unique suffering? They were dispossessed of their ancestral land. And with it, they were dispossessed of the very right to exist – under the legal doctrine of terra nullius.

Indigeneity is “the ancestral bones in the land, that is the source”, Pearson has said. “At the core of all Aboriginal customary law, you find these elements – the ancestral tie to the land. The person born from that land, who remains attached to the land, and whose spirits will one day return to it. I would venture to say that these ideas are universal to all indigenous conceptions of relationship to their country, the world over.”

It’s a concept that conservatives might recognise in the words of the great conservative philosopher Edmund Burke’s famous definition of society as “a partnership of the dead, the living and the unborn”.

The Coalition’s spokesperson on Indigenous affairs, Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, this week was asked by a journalist: “Would you accept there have been generations of trauma as a result of that history?”

Price: “I guess that would mean that those of us whose ancestors were dispossessed of their own country and brought here in chains as convicts are also suffering from intergenerational trauma. So I should be doubly suffering from intergenerational trauma”, a reference to her own background with an Indigenous mother and a father descended from an Irish convict.

This line won her laughs and applause from some in her audience including the leader of her party, the Nationals, David Littleproud. Her implicit message – all races suffer the same, why should one get a Voice and not others? But, of course, it’s an ahistorical effort to equate two very unequal histories.

While Indigenous Australians were dispossessed of their land and their rights, convicts who’d served their sentences often were granted land by the colonial administration and recovered their rights in full. One group was systematically excluded from the economic and social systems of colonial Australia while the other was included.

In fact, the late historian John Hirst established that convicts in Australia, even as they served their sentences of forced labour, enjoyed greater rights than English domestic servants in London. For instance, an English employer in London was within the law to beat his domestic servant at will. A landowner in Australia could only beat his assigned convict labourer if a magistrate gave permission. Whereas an Australian native could be mistreated with impunity.

Price also claimed that Indigenous Australians suffered no ill effects from colonisation. Well might Littleproud laugh at this; Price’s radical denialism is laughable.

And yet the No campaign claim – the straw man argument that the referendum is racially divisive – still stands unchallenged by the Yes campaign. In private, key Yes campaigners confront it. One, for example, says that “what’s really unequal and unfair is that Indigenous Australians live an average of eight years less than everyone else because what we’re doing right now is not working”.

In public, they talk past it. Why? One agrees that “absolutely it’s a weakness of our campaign”. Yet he says that “they’ve got us snookered – we’re unable to argue back because any commentary by us is seen as accusing them of being racist. It’s Orwellian but it’s effective.”

He has a point. When Indigenous Yes campaigner Marcia Langton this week said that the No campaign drew on arguments that were “racist” and “stupid”, it drew a ferocious response that dominated the news for days and blocked out campaign efforts. So the Yes campaign feels constrained to concentrate on the positive: “Every minute I spend arguing against their case is a minute lost in putting the positive case of our own.”

The No campaign’s “rancid dishonesty” of racial divisiveness, as Pearson called it, is strangling the Voice, but the Yes campaign feels powerless to confront it. This is an exquisite dilemma.

Another leading Yes advocate says that their campaign is hampered by “a massive educational hole” among the broader public. We are limited in how much we can push the point of Indigenous disadvantage, he says, because many Australians aren’t aware of its seriousness.

For example, in earlier focus groups conducted for the Yes campaign, only two out of 30 voters had heard of the Closing the Gap targets. “When you explain it to them, they say ‘I didn’t know that’ and they get embarrassed and then they get defensive. Most of them see the Aboriginal flag on the Harbour Bridge and they hear Welcome to Country ceremonies and think things are looking up for the blackfellas in this country.”

Confronted with the depth of persistent disadvantage, like the fact that a young Indigenous man is more likely to go to jail than to university, “they go from embarrassment to resistance very quickly”, says the campaigner, and that is not the campaign’s desired effect.

All of which helps explain why the opinion polls show that support for the Voice has been in continuous decline all year. But the campaign proper begins on Sunday. The Voice advocates say that the tide of public opinion can be turned in the remaining four weeks.

Labor’s national secretary, Paul Erickson, cheered the Labor caucus this week when he told the assembled MPs and senators that the referendum was “up for grabs”.

In between the committed Yes voters and No voters was a huge hinterland of around 30 per cent of the electorate or 5 million people who were gettable for Yes, Erickson said. This included 8 to 10 per cent who were in the “don’t know” column and another 20 per cent of “soft” or uncommitted No voters.

Don’t just give people information about the referendum, he urged them, “tell them it’s time to listen to what Indigenous Australians are asking for”.

No shit.

Peter Hartcher is political editor.

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.

Most Viewed in Politics

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article