Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

Though it’s an increasingly controversial stance among those who subscribe to the gentle parenting movement, I make my children hug their grandparents.

To some, enforcing my two young kids these kinds of rules is considered to be on par with sending them to Neverland Ranch for a sleepover.

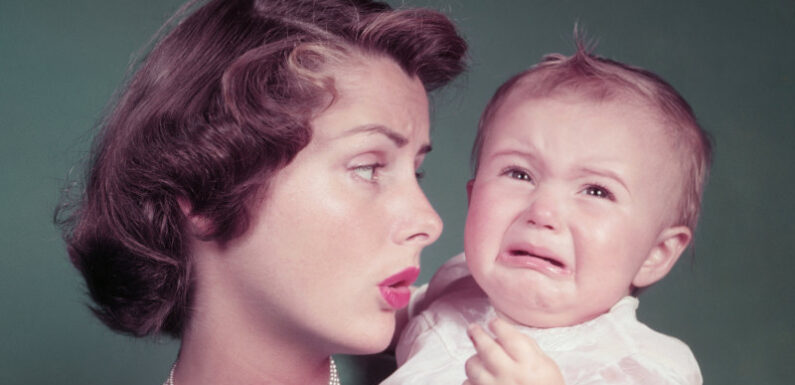

Our “child-focused” culture in which “the ethos is that we should be hyper involved, hyper present, hyper emotional and hyper organised” is, says clinical psychologist Dani Klein, leaving many parents overwhelmed.Credit: Getty Images

To be clear, the decision comes from me; it’s not something the grandparents are calling for. They’re more than understanding, telling me, “They’ll come to us when they’re ready,” while I sharpen my death stare and full-body sign language for, hug your grandparents or no Bluey for the rest of your life.

If my kids don’t feel like it and the grandparents don’t mind, you might wonder why I’m sticking with it for the simple fact that I believe it’s important to establish clear boundaries and expectations from an early age.

The Internet is littered with advice for modern parents. Where one resource says it’s important to teach your children it’s okay to say no and for the adults in their life to respect this, another recommends adults use adoptive phrases such as “when you feel safe, come to hug grandpa.”

Last month, Good Weekend reported that “snowplough parents” – who clear physical and emotional obstacles for the children – are to blame for worsening child behaviour in schools because much of modern parenting encourages you to go with what the child is feeling or wants at any given moment. If they don’t want to hug grandpa, these parents say, don’t make them. And if you do make them, it’s an abuse of their agency.

I worry about what the long-term outcomes of a parenting style that elevates children’s feelings above all else will be.

As an example, my two-year-old wanted ice cream for breakfast this morning. After calmly telling him no, he kicked, screamed, and cried. According to those who subscribe to gentle parenting, I would talk to him in a quiet, calm voice and help him reflect on his emotions, so he can learn to self-regulate. A response would go something like this: “I know you would love to eat ice cream, and you’re frustrated that I won’t give you any, but ice cream isn’t breakfast food! Let’s discuss why you feel you need a treat right now.”

Instead, I stood at the freezer, repeatedly said “no” in a firm voice and, when he gave up, I made him toast. Most of us would prefer ice cream to toast, but more than needing him to understand the nutritional aspects of his diet or for me to psychoanalyse his need for ice cream as unmet emotional needs, I want him to learn that my “no” means no. At his age, that’s the response he needs to learn most urgently.

Similarly, hugging the grandparents seems like a small hill to die on, but for me, it represents a pattern of teaching kids to relate to others where their feelings are of prime importance, which results in the endemic disrespect we’re seeing in schools. As one expert told Good Weekend, a “crisis of adult authority” is what’s behind growing disrespect in classrooms. Rather than enacting discipline, we’re psychologising kids’ behaviours, putting their feelings front and centre.

According to Rebecca Wheeler, director of RWA Psychology, gentle parenting gets a bad rap. She believes that it’s possible to strike a balance and distinguishes between gentle parenting and “limitless” parenting, or “permissive” parenting.

“We want to make sense of our child’s behaviour, even if we don’t agree with it because then we can work out what to do with it,” Wheeler says, explaining that it’s important to recognise what your child is feeling at the same time as teaching them what others might be feeling. In the case of hugging their grandparents, for example, a happy medium could sound something like, “I know you’re upset because I made you stop watching Bluey to come over here, but your grandparents really look forward to your cuddles.”

Kirrilie Smout, the director of Developing Minds in South Australia, says that rather than viewing parenting decision as right or wrong, it’s important to weigh up the benefits and consequences. “The potential benefit of making your kids hug their grandparents is to say: even if you have a moment of discomfort, our long-term values are that we care about how other people feel.”

But she also emphasises caution when it comes to a child’s bodily autonomy to avoid establishing a pattern of thinking that might allow something sinister to happen.

Instead, Smout suggests giving your child choices. For example, “would you like to give grandma and grandpa a hug, or would you like to give them a high 5? Would you like to tell them what a great time you’ve had or tell them that you love them?”

Though parents want to show we are in charge, it’s also important to address our fears and prejudices when making decisions.

Like most parental predicaments, there are no straightforward answers. Next time, I’ll tell them if they hug their grandparents, they’ll get ice cream for breakfast and unlimited access to Bluey.

Cherie Gilmour is a freelance writer.

The Opinion newsletter is a weekly wrap of views that will challenge, champion and inform your own. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in Lifestyle

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article