More often than not, Hayao Miyazaki’s heroes have been young women — from Ponyo to Princess Mononoke, mischief-seeking Kiki to the two sisters spirited away by furry forest guardians in “My Neighbor Totoro.” That’s the most obvious departure the anime maestro’s fans will notice in “The Boy and the Heron”: It’s about a boy, Mahito Maki (voiced by Soma Santoki), grieving the loss of his mother during wartime. He’s surrounded by women, but this quest falls on the shoulders of a character who’s reportedly closer to Miyazaki than any of his previous protagonists.

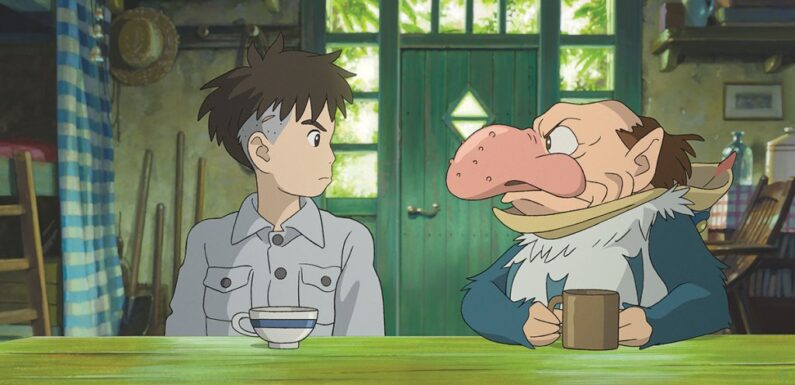

In 2013, the world-renowned toon auteur announced his retirement from feature filmmaking. He disbanded Studio Ghibli, the company he’d co-founded, and let its artists scatter to find work where they could. But Miyazaki couldn’t stop drawing (that’s how he “writes,” by sketching the dream-like adventures into storyboards). And this time, the adventure he imagined centered on a 12-year-old boy and the gray heron he discovers flapping about his new home — a nuisance that eventually reveals itself to be a disguise for another of Miyazaki’s surrealistic creations, when a bald, troll-like figure with great big teeth and a bulbous red nose emerges from within its hinge-like beak.

It’s probably best not to set your expectations too high for “The Boy and the Heron.” That’s easier said than done with Miyazaki, who’s considered by many (this critic included) as the most visionary artist to have worked in animation since Walt Disney. What could be so compelling to bring Miyazaki-san out of retirement? Would this be some kind of career-encompassing project? Better to think of “The Boy and the Heron” as the bonus round — a worthy but mid-range addition to a remarkable oeuvre that expands his filmography without necessarily topping it. It’s a more fitting finale than 2013’s “The Wind Rises,” but still might not be his last.

Much of what the film does and depicts will seem familiar to fans. The style is consistent with Miyazaki’s most beloved films, right down to the purgatory-like wonderland Mahito spends most of the movie exploring. There are adorable white bubble-blobs called “warawara” on the other side that inflate themselves and float up into the sky, which look an awful lot like his egg princess or the ghostly kodama from “Princess Mononoke.” And there’s a “fire maiden” named Himi (mononymous singer Aimyon), who might be Mahito’s mother, obliging him to make a choice between reconnecting with her and returning to the real world.

The “real world” in this case is a harrowing place touched by tragedy and war. The movie opens with the fire-bombing of Tokyo — an intense scene that recalls that early Ghibli masterpiece directed by Miyazaki’s late colleague and mentor Isao Takahata, “Grave of the Fireflies.” Mahito hears the sirens and rushes downtown, where his mother is trapped in a burning hospital. Unable to save her, the boy is sent by his father, Shoichi (Tokuya Kimura), to live with his aunt, Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura) — a dead ringer for his late mother — in a remote house surrounded by nature. No sooner does Mahito arrive than a heron swoops past the boy’s head.

Natsuko sees the bird as an omen, but it’s more than that, stalking Mahito as he explores the ponds and forests nearby. Mahito doesn’t fit in at school, where he fights with other boys and resorts to smashing his head with a stone, hoping the injury will convince his dad to let him stay home. That’s one of the film’s more startling details and must have some connection to Miyazaki’s personal history, though that’s mere conjecture until such time as the director agrees to give interviews. The movie opened (first in Japan on July 14) without traditional marketing to contextualize what audiences were seeing. Box office was strong out of the gate, but has since fallen behind other Ghibli releases.

In the United States — where Disney rereleased Miyazaki’s key films, and revivals by U.S. distributor GKIDS regularly sell out — there’s an audience ready to embrace his latest effort. But “The Boy and the Heron” is hardly the ideal entry point for someone newly sampling the director’s work. Oddly, it feels like a late-’90s Miyazaki film that’s been dusted off and is just now being shared for the first time abroad. (My advice: Start with “Totoro” or “Spirited Away,” just to get a handle on how fantasy can erupt from and intrude on the everyday concerns of a child in his movies.) Here, young Mahito discovers an enormous tower on the estate. At first, he pokes his head in through a half-blocked passage, unable to enter, but later, after Natsuko disappears, he follows the Heron (not even remotely “cute,” but realistic looking, voiced by a memorably croaky Masaki Suda) down an enchanted tunnel into what feels like the grand hall from “Beauty and the Beast.”

There, stretched out on a sofa, is a woman who looks like Mahito’s mother — the first of many illusions in what unfolds into an epic journey into Miyazaki’s eastern spin on the Greek underworld. Accompanied by the Heron (who’s now revealed his much uglier true form), Mahito demonstrates bravery as he ventures forth through gates and across seas into territory that Miyazaki seems to be making up as he goes along. In a sense, that’s what makes his storytelling style so unique: Rather than follow a traditional three-act structure, Miyazaki follows his imagination, such that audiences can’t possibly guess where the narrative will go next.

True to form, “The Boy and the Heron” proves unpredictable, but it’s also within the realm of Miyazaki’s earlier work, which is both comforting and slightly disappointing. He hasn’t done anything to tarnish his filmography. Nor has he expanded it in the way “Spirited Away” did. The Heron is an unpleasant yet detailed character, which contrasts with dozens of rudimentary, half-anthropomorphized parakeets — pink, green, yellow and blue birds with beady eyes and bulbous nostrils (these are not Ghibli creatures people will be getting tattoos of anytime soon). The movie’s full of visual ideas, from a swarm of frogs to the busybody maid who becomes a warrior pirate on the other side, but it mostly reminds how familiar our world already is with the one Miyazaki’s been weaving all these years.

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article