How much is Paul Westerberg like Bob Dylan?

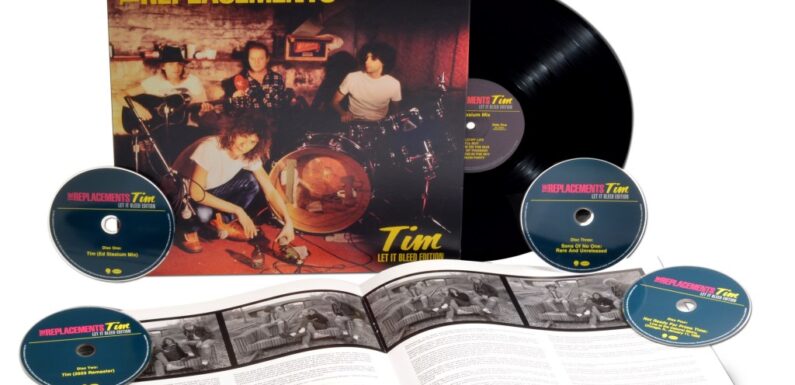

That’s a provocative question — maybe one we need to save for when we know each other better. So let’s just start a related, but easier, one. How much is the Replacements’ “Tim: Let It Bleed Edition,” a just-released boxed set that commemorates that band’s classic 1985 album “Tim,” akin to another boxed set that came out earlier this year — Dylan’s “Fragments: Time Out Of Mind Sessions 1996-1997,” an expansion of his classic 1997 album “Time Out of Mind”?

That’s an easier conversational icebreaker. Beyond the fact that the two original releases might be right next to each other in your collection, if you happen to be insane enough to alphabetize albums by title instead of artist, there’s the fact — well, strongly held belief bordering on fact — that both “Tim” and “Time” are rock masterpieces that share a common fundamental flaw: problematic mixes. Mixes that have been mutually, coincidentally corrected with spectacular 2023 do-overs. Yes, there are diehards who continue to contend that producer Daniel Lanois’ swampiness on the original Dylan album did not need to be de-murked. There will probably also be a few (but fewer) who’ll argue that the Replacements album they have known and loved for 37 years was just fine with all of the digital reverb laid on by that record’s producer, Tommy Erdelyi (aka Tommy Ramone). Both Lanois and Erdelyi made fundamentally phenomenal records; nothing about their roles in those records constitutes villainy.

But most fans will surely agree: One of the benefits of hindsight is that not everything needs to sound like it was recorded in a Grand Central Station lavatory. And while it’s good for an album — just like a woman — to maintain a little mystery, clarity can be next to godliness, when it comes to rendering utterly fearless rock ‘n’ roll.

So forgive me if I shed some tears of joy over “Tim: Let It Bleed Edition,” a collection that instantly vaults nearly to the top of my list of the most essential album-centric boxed sets ever released. And tears of regret, that I spent more than three and a half decades enjoying one of rock’s best albums while also recognizing in the back of my head that something about it sounded kinda off. Also, let’s include some tears of embarrassment, since it’s now clear I spent almost 40 years misquoting some of the lyrics — although Westerberg was such a proud purveyor of mumblecore that no remix is going to suddenly turn “Tim” into an album Henry Higgins would use as an elocution demo LP. Raise your hand if it took till now to realize that Westerberg is singing “Wait on the sons of no one,” not “We are the sons…,” in “Bastards of Young”? (No one? Fine, then.)

Going on and on about Ed Stasium’s new mix threatens to take up space that could be spent waxing on about the basic album itself, which might be helpful for a generation that has never been cajoled into listening to “Tim” at all before, in any form. So just a few more words about Stasium’s work — and that of reissue producers Bob Mehr and Jason Jones, who helmed the project for Rhino. Stasium was actually a frequent collaborator with the late Erdelyi, on records by the Ramones and others in the ‘70s, and so there’s a fitting way in which he is collaborating with the original producer again, from across the great divide, in a way one hopes Erdelyi would not find to be a desecration. The oddities about the original mix cited in Mehr’s and Stasium’s liner notes come down to: arguably too much digital reverb on Westerberg’s vocals and Chris Mars’ snare drum; a lack of stereo panning that created an essentially mono effect; and a lot of Bob Stinson’s guitar parts (which were minimal anyway, since he rarely showed up at the studio) being left on the cutting room floor. (Westerberg himself told biographer Mehr: “I can remember listening to it and thinking that it sounded kinda like crap, but not watning to go back in. We were just glad it was done.”)

Besides adding a few tantalizing extra guitar or even piano licks here and there, Stasium’s mix has made the whole thing sound utterly crisp, putting the band right there with you, and not even in a bathroom with you. Almost everyone can agree this is an improvement, even if we might have differing takes on how this would have been received had it been released this way in 1985. My colleague Jem Aswad wrote that it was probably a deliberate choice to add that extra layer of sonic goop in the ‘80s, so that the album would be less accessible and actually compromise possible mainstream success, forestalling any charges of selling out as these former Midwest punk-scene denizens navigated a major-label deal for the first time. I hear it more as “Tim” now just sounding like a simple successor to the previous year’s “Let It Be,” hewing closer to their no-frills roots. But it is beefier, even while it’s more bare-bones. Maybe we’re both right: It’s possible the Stasium approach we heard now would have felt more punk-rock in its fashion then but also, thanks to his subtle, pro-grade enhancements, like more of a mainstream monster, too.

The new mix is just part of the reason to pick up the four-CD “Let It Bleed” edition, if probably the most crucial one. There’s also a disc devoted to a remastering of the original Tommy Erdelyi, which the reissue producers say corrects the mistakes that were made when the album was first mastered for CD a few years after it came out, making a questionable mix far worse. There’s a live disc, recorded at a Chicago club in ’86 during Bob Stinson’s last run with the group, that’s nearly as good as the previously issued “Live at Maxwell’s” album. And the disc of alternate versions and outtakes, most previously unreleased, makes for a great listen by itself, as well as satisfying some historical curiosity about things like how some early Alex Chilton-produced demos compare with the finished album.

The band attempted multiple versions of “Can’t Hardly Wait” before Westerberg abandoned it and saved it for the hit that it became when he nailed it on the next album. It was wise that they held it back till they got it right, but there’s no doubt that “Tim” would have seemed like even more of a masterpiece than it already did if they had tagged on the more rugged version they attempted in ’85. Conversely, there’s a “Can’t Hardly Wait” tryout accompanied solely by cello — go figure, and go enjoy. In general, Westerberg was making the right decisions about what should go on an album, and in what style, but the alternate-universe renditions are thrilling in their own right. Take the early Chilton demo of “Kiss Me on the Bus” that sounds like a pure punk rager; it eschews any of the jangly magic and adolescent romanticism that made the final version a classic, but it sure is a kick to hear them go so far off the emotional mark and play the tune like it’s actually supposed to be angry.

In the end, “Tim” existed in an echo chamber in more ways than one — cementing the group’s status as “band of the ‘80s” (U2 and R.E.M. withstanding or notwithstanding) among the critical intelligensia and those with similar sensibilities, even as the album peaked at a lowly No. 192 and sold a modest 75,000 copies. Why is it still so enrapturing today?

There is plenty to be said about that, but some of the quotes from observers or the band members themselves in Mehr’s liner notes — which are nearly book-length, and awesome — get at it as well as anyone could. Says Jeff Tweedy: “For a sensitive Midwestern guy to sing about his feelings and and do it in an environment that was completely chaotic and irreverent was a real revelation. That made it feel like folk music.” Peter Buck also used the M-word in describing the “Midwestern fatalism” of songs like the boozy barroom closer, “Here Comes a Regular.” Erdelyi, speaking of the ferocious opener, “Hold My Life,” said, “I enjoyed the fact that it sounded onfused, that (Westerberg) sounded like he was lost, trying to climb out of a hole.” Westerberg himself made it sound as if he were more revealing in his lyrics than he was in real life: “I used to mind my deepest feelings and use that for the songs, then keep my relationships light,” he confessed. The album came at a turning point in his writing when he was discovering that “the quieter songs can be more frightening and powerful than the old rockers” — yet he still couldn’t resist writing pure rawk like “Dose of Thunder” and “Lay It Down, Clown” amid the heightened singer/songwriter sensitivity. The album represented a perfect nexus point, marrying Westerberg the proud fool and Westerberg the humble poet laureate.

On a purely musical level, said Erdelyi, “His voice had a John Lennon quality, like when Lennon was singing hard on ‘Twist and Shout.’” Westerberg himself said “I Will Dare” when it came to making the same kind of bold comparison: “We were a garage band playing at extreme volume, yet I was playing things like sixths and major seventh chords, which immediately made people say, ‘Well, that’s the Beatles.’” Maybe they were a Fab Four for ‘80s kids — the Beatles disguised as a gang of cranky, sloppy, unpredictable lushes, defying you to find the real prowess and musical sophistication beneath the noise, because doing anything so old-fashioned as presenting a great melody like a great melody ought to be presented was bragadocio unbecoming of a member of the post-punk generation, or of a Minnesotan.

Which is where we return — as threatened! — to how Westerberg is like Dylan. Whatever might be in the shared water in that part of the world, it turned out two world-class rock heroes who, at their core, are cocky smart-asses with possibly conflicted feelings about how far down their sleeves to wear their hearts. Neither ever placed a premium on an eagerness to please, although the chief Replacement did a better job of sabotaging mainstream success than Dylan was ever able to. What’s most striking is how, for whatever reasons, they have retreated somewhat and become even more mysterious as the years have gone on — Dylan by hiding in plain sight, always on the road but rarely explaining himself in stage patter or interviews; Westerberg by becoming more of an actual rock recluse.

We may want a lot more shows or records than he’s given us in the 21st century (Westerberg’s last full, official solo album came out 19 years ago). But when he gave the world a “Tim,” how much more does he owe us? If anything, his disinterest in providing “product” anymore only bolsters the feelings that you get from that amazing run of original records. Alienation becomes a kind of humblebrag for so many rockers, but when Westerberg sings about feeling disaffected, you can really believe he wasn’t kidding around. And “Tim” hasn’t dated; it almost sounds like a record a sixtysomething guy could make, albeit a sixtysomething guy with a huge surfeit of energy. Even when Westerberg is singing about being a kid in “Bastards of Young,” he sounds like an old soul. And in 2023, it’s still enough.

But if the massive show of renewed adoration for “Tim” suddenly gave Westerberg the urge to reemerge with a fresh set of new classics — “Jim,” “Billy,” “Roger,” whatever — we’d take an autumnal rose from him, under any other name.

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article