A handful of big international art fairs are obligatory annual destinations for the world’s major collectors. Only among the second-tier fairs is there real competition, as cities compete to attract wealthy art tourists seeking something a bit different.

All these fairs dream of getting the world’s über-galleries to participate, but the real interest lies with the local product. One can find the same high-priced, big-name artists in Basel, Miami or Hong Kong, but collectors who travel to Australia or New Zealand are willing to explore new fields, make discoveries and pick up a few bargains.

The Aotearoa Art Fair in Auckland makes a virtue of its smallness and originality. In the harbourside convention centre known as The Cloud, one finds no more than 41 galleries, mostly arranged on either side of a long corridor, with a group of emerging galleries clustered upstairs. Even the special projects section, curated by Micheal Do, is deliberately off-beat, showing conceptually based installations not affiliated with participating galleries.

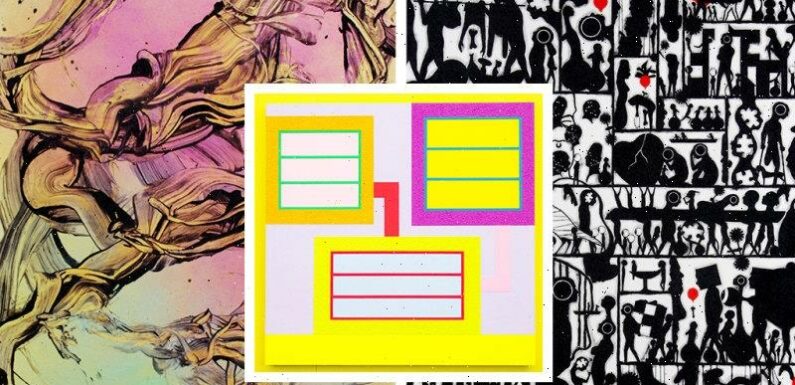

Geometrical abstractions by New York artist Peter Halley.

The roll call of participating dealers is almost exclusively kiwi, allowing for a few adventurous Aussies, such as MARS gallery from Melbourne, who were showing photographs by rising star, Atong Atem; and Yavuz, with galleries in Sydney and Singapore, who showcased new paintings by Guido Maestri.

The attraction of this compact, user-friendly fair is that it allows for a comprehensive overview of one of the world’s most vital, quirky and energetic art scenes. One can’t stay long in New Zealand/Aotearoa without becoming aware of the profound differences that exist on opposite sides of the Tasman. For a long time, Australia has clung to the wistful belief that it plays a meaningful role in the international art circuit, but New Zealand has been happy to accept its marginal status. The result, paradoxically, is a kiwi art scene that often seems more closely connected with the rest of the world.

Presumably, it’s a matter of feeling you’ve nothing to lose and everything to gain, resulting in an outward-looking approach. Australian galleries, by contrast, have been relatively insular, although that is beginning to change. At present, there is no Australian equivalent for Auckland gallery, Gow Langsford, which presented geometrical abstractions by New York artist Peter Halley on a lurid yellow wall. The gallery’s other featured artist, Judy Millar, divides her time between Auckland and Berlin, and shows in Sydney with Sullivan + Strumpf.

Shown at Gow Langsford: ‘Marilyn’ (2022), oil and acrylic on canvas by Judy Millar, another of NZ’s most internationally recognised artists.

Fox Jensen (Sydney) and its Auckland branch, Fox Jensen McCrory, is even more internationally focused, showing an extensive range of artists from Europe and America, alongside a select group of Australians and New Zealanders. Overall, only eight galleries at the fair had an international presence but a bigger group of overseas participants are expected to be present when the fair makes a quick return, from March 3-7.

The 2022 fair was held in November as a result of the COVID-19 crisis, after the galleries insisted it should go ahead even if it meant a very short turnaround with the following year. This could be interpreted as a sign of supreme self-confidence, or desperation.

Based on one week’s experience, I’d do with the former explanation. When I first visited New Zealand more than 30 years ago, it was like travelling in a time tunnel back to the 1950s. Today, a city such as Auckland is a small metropolis, with all the boutique shops, five-star hotels and fashionable restaurants that make tourists feel comfortable. The commercial galleries are a vital part of the mix.

For a vivid sense of what life used to be like, the essential experience is an excursion to McCahon House in the leafy suburb of Titirangi. Colin McCahon, revered as New Zealand’s greatest modern artist, lived in this tiny cottage with his wife and four children, from 1953-1960, while working as a cleaner at the Auckland Art Gallery. In time, he would ascend to the post of acting director.

Colin McCahon in his studio in 1961.

McCahon’s paintings fetch such gigantic prices in today’s art market, it’s startling to see how he lived, with a bedroom the size of a closet. Meanwhile, the four kids were accommodated in bunks downstairs, with only a curtain of hessian bags separating them from the weather. The fresh air was considered healthy.

McCahon House – a noble title for a modest dwelling – reveals the provincial poverty of life in New Zealand in those years. A few minutes drive away, one arrives at Te Uru, a massive contemporary art complex designed by architects, David Mitchell and Julie Stout. Opened in 2014, this impressive building stands as a symbol of the country’s booming cultural aspirations.

A statement on a much grander scale is the Gibbs Farm, 47kms north of Auckland, visited by appointment, this is one of the world’s great sculpture parks, featuring the largest-ever works by artists such as Anish Kapoor and Richard Serra, along with other international figures such as Andy Goldsworthy, George Rickey, Daniel Buren and Sol LeWitt. There are kiwi sculptors such as Neil Dawson and Chris Booth, and even an Aussie, Andrew Rogers.

When Alan Gibbs bought the property in 1991 he was already established as a major collector of local and international art. Along with the sculptures, he has stocked the grounds with giraffes, zebras, bison, emus, and a host of other exotic species. The landscape itself – a succession of vast, undulating grassy slopes – is as diverting as the art or the animals.

Andy Leleisi’uao’s Contemplation People (2020-21).

Thirdly, there’s the Chartwell Collection, a massive repository of kiwi and Australian work, put together by businessman and occasional artist, Rob Gardiner, and his family. The Gardiners have been collecting the most adventurous art they can find since 1974. For the past 25 years, a partnership with the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki has resulted in biennial collection shows, the most recent being Walls to Live Beside, Rooms to Own, which runs until March 23. No private collection in Australia has taken the same chances over such an extended period.

Along with the contrasting attractions of McCahon House and the Gibbs Farm, I spent the best part of a week visiting commercial galleries and alternative spaces, familiarising myself with a city I hadn’t visited in four to five years. I won’t offer a lengthy report, although it was enlightening to meet Scotchman, Scott Lawrie, who spent 14 years in Australia before starting his art gallery in Auckland, and fascinating to hear about Frances Hodgkins (1869-1947) from dealer Jonathan Grant, who has made a long-term study of the woman recognised as New Zealand’s first major Modernist painter.

The most noticeable change in New Zealand art since my previous visit, is a new emphasis on the art of the Pacific, the catalyst being a landmark exhibition of contemporary Māori art held earlier this year at the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki. Although New Zealand/Aotearoa has always been more genuinely bicultural than Australia, there’s been a long-running argument as to whether Māori work should be considered as a separate category or integrated within the broad field of contemporary art. Those who favoured separation were often Māoris, who declined to have anything to do with the Pakeha art establishment. For rising artists such as Andy Leleisi’uao, of Samoa, with whom I had a long conversation, it’s the growing willingness of dealers, museums and collectors to embrace contemporary Pacific art that makes this an exciting time.

The Aotearoa Art Fair made a huge effort to be inclusive, providing space for a Māori art centre such as Toi Māori Aotearoa from Wellington, which showed pieces that traverse the whole spectrum of traditional and contemporary activities, even tattooing. This evolving cultural dialogue, which has an intensely political aspect, is a shot across the bows for an Australian art establishment in which all things Indigenous are taking on new importance. Eventually, we’ll need to reach a point of accommodation where artists of all persuasions feel comfortable, but while the dust is still rising across the Tasman, it would be wise to keep an eye on our neighbours and see how it all plays out.

The Aotearoa Art Fair will take place from March 2 to 5. John McDonald was a guest of the Aotearoa Art Fair.

A cultural guide to going out and loving your city. Sign up to our Culture Fix newsletter here.

To read more from Spectrum, visit our page here.

Most Viewed in Culture

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article