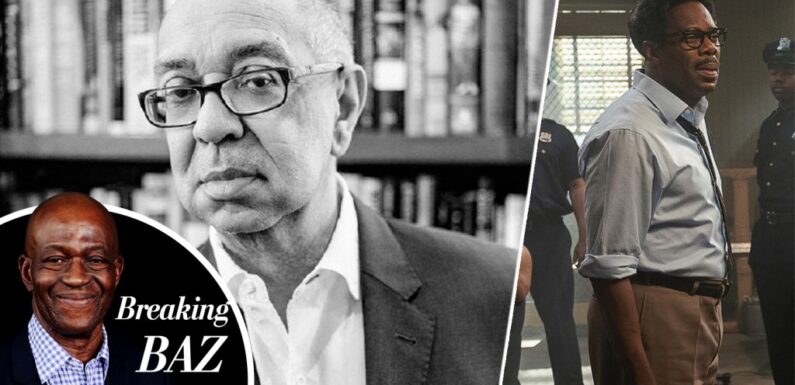

EXCLUSIVE: Filmmaker George C. Wolfe was not interested in doing what he termed “icon crap” in his movie Rustin, about the multi-layered life of Bayard Rustin, regarded as one of the most influential organizers of the Civil Rights Movement and the architect of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which took place 60 years ago this week.

“You have to have an extraordinary degree of irreverence and approach it like, ‘This is a human being.’ Because if you’re doing icon crap, it is very easy for you to fall into boring or reverential, and we have statues for that,” said Wolfe (Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks) of his film that stars Colman Domingo (Euphoria, Candyman, Fear the Walking Dead) as the man who often was at Dr. Martin Luther King’s side.

Related Stories

SAG-AFTRA Tells Members It's OK To Promote Their Movies With Interim Agreements At Film Festivals

'Suits' Marks 6 Weeks Atop Nielsen Streaming Charts; 'Futurama' Reboot Premiere Prompts Surge In Viewership

Many have opined that Rustin has been neglected by history.

Ten years ago, when President Barack Obama awarded Rustin the nation’s highest civilian honor — the Presidential Medal of Freedom, posthumously — he noted that Rustin was “denied his rightful place in history because he was openly gay,” and he implored people to honor Rustin’s memory by “taking our place in his march towards true equality, no matter who we are or who we love.”

Fitting, then, that Rustin should be the first feature from Michelle and Barack Obama’s Higher Ground Productions, which has its deal at Netflix.

Bruce Cohen and Tonia Davis produced Rustin, with the Obamas credited as executive producers along with David Permut, Alex G. Scott, Daniel Sladek, Chris Taaffe and Mark R. Wright.

Rustin will screen September 13 at TIFF – and who knows where else it may pop up before then – and is scheduled to be released in theaters on November 3. It hits Netflix on November 17.

Domingo stars with British actor Aml Ameen as King, Glynn Turman, Audra McDonald, Chris Rock, Gus Harper, Johnny Ramey and CCH Pounder. Rock and Turman starred together on the fourth season of FX’s Fargo, and Turman and Domingo starred in Wolf’s Oscar-nominated Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom.

Wolfe views Rustin, who died in 1987, “as being incredibly heroic and incredibly influential, and history is frequently unfair. I think he did amazing things and had a huge impact.”

The director cited the Rev. Al Sharpton as a recipient of Rustin’s benevolence.

Sharpton recently saw the film and noted how early on in his career he met with Rustin. ”Bayard made sure that he wrote him a check, and that’s how Sharpton began his first organization,” Wolfe told Deadline. “I think he’s so really very fascinating in the way he affected so many people.”

Rustin was raised by his grandmother, who was a Quaker, and she instilled in him “that sense of being of service.”

Many of his closest allies were raised with the same mantra ringing in their ears: “What have you done today to make yourself useful?”

It was that thought process “that belief that being of service, that doing something for the race, that doing something for humanity, that doing something for the country” ingrained “an incredible sense of responsibility,” in Rustin, Wolfe told me during our Zoom.

The man had a playful side too.

Back when he was playing offensive lineman for the Westchester Warriors, ”he would knock down an opponent, and then he’d help them up and recite a line of poetry,” Wolfe noted.

“I mean, it’s another time. It was a sense of grace,” he said.

Rustin was a conscientious objector during World War II, “and while he was in prison, he tried to get the warden of one prison to change all the racial discrimination that was happening there. He went to visit the internment camps when the American Japanese were imprisoned during the war.”

Shrugging, Wolfe observed that such actions were “embedded in who he was. it’s just how he was wired. It’s how he was raised. There was such an incredible sense of grace and a sense of curiosity.”

And Rustin’s curiosity will surprise people.

“It’s sort of ridiculous, and it’s wonderful and extraordinary that he made an album called Elizabethan Songs & Negro Spirituals, in which he sings just that.

Wolfe laughed and said “And he’s from Westchester, Pennsylvania!”

If something caught Rustin’s curiosity, said Wolfe, “he followed his instincts just to see where it would lead.”

That curiosity often caused friction with those who did not approve of his sexuality and how he went about looking for comfort.

But those same people, particularly within the Civil Rights Movement were, claimed Wolfe, “in awe of his organizational skills.”

He pulled off the March on Washington in less than eight weeks because he was “legendary for his organizational brain,” said Wolfe.

The director told me that Rustin would exhort volunteers working with him to “go home and imagine the march from beginning to the very end. Imagine every single detail and keep thinking and looking for anything that you might have left out, that we might have left out.”

Seemingly mundane details like banks of phones for journalists, plenty of water, there was even an ice cream truck. A sound system was installed “because a sound system is how you turn a crowd into an audience.”

Another lovely touch that Wolfe captured is that when somebody would call to arrange travel, those picking up the call would assume one name, rather than shouting out for the person the caller sought. “It was a stroke of brilliance,” said Wolfe.

Also a stroke of genius to cast Colman Domingo to portray the the great organizer.

“There were a bunch of people who wanted to do it, and Colman’s name came up very early on,” Wolfe recalled.

“Over time his name and his rhythms and his face started to appear more and more to me. There was no audition. It was just … inevitability emerged, and it was him.” And once the decision was made, the actor did his research on speaking patterns and on how Rustin carried himself.

Wolf’s a great believer in rehearsal for film, a factor honed from his many years writing and directing for the theater. He and his cast sat “spending time and thinking and talking about it and rehearsing and rehearsing so that you’re peeling away that which is underneath and exploring and evolving and discovering that he was a man who had many weapons.

He was “incredibly intelligent, he was very charismatic, he was very witty, his mind worked very, very quick.

“He had anger, but he used it when all else failed, or when the circumstances became such that the most rational, clear and clean and evolved part of him became overwhelmed because he was in the presence of such extraordinary inhumanity. For instance, like when the authorities were hosing down kids or anytime he was in the presence of something that had an extraordinary degree of brutality with it,” Wolfe explained.

Another weapon was image. “What the early ’60s Civil Rights Movement understood brilliantly was image. And when the kids were going through non-violence training, there was a whole sequence on how you dress, how perfect your clothes were, how perfect everything was, so that if you’re sitting a a lunch counter and somebody is squirting you with ketchup or mustard and screaming and yelling at you, who’s the civilized-looking person and who’s the barbarian?”

Growing up, I too learned those lessons watching TV at home and seeing smartly dressed men and women marching for equality and freedom across the Atlantic in the United States.

“Absolutely,” Wolfe agreed.

“It’s fashion as a weapon. It’s fashion as being a part of your arsenal, of human behavior and interactions. Part of it was informed a little bit by knowing that there was judgment coming from the other side. But the other part of it was just how you carried yourself. … It is part of a weapon that was used very heavily and very successfully at that time period,” he remarked.

The higher-ups at the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) would use Rustin’s homosexuality as a weapon against him. “They did because it was believed that the white power structure, the news media, the FBI would use all of this to discredit the movement. It was a concern, and it was a legitimate concern because J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI would use and do anything to discredit.”

Also, Rustin’s early communist leanings and having been a conscientious objector, on top of being gay and out of the closet, “spells bad, bad, bad in terms of image, in terms of projecting a positive image. He wasn’t out in terms of 2023 out. But in terms of 1963, he was a very out homosexual.”

Rustin understood both the complication and his responsibility to the march, “but he also understood he was not going to deny who he was.”

Wolfe recited one of the film’s great lines.” It’s where Bayard says, “I’m trying to figure out how many toilets there needs to be. I’m trying to figure out how to get water there. I don’t have time to be ashamed. You know, maybe when I have some time, I’ll get around to feeling shame about my sexual identity. But right now, I got to organize and to get at least a hundred thousand people to D.C. So I don’t have time for all of that.”

Rustin did not have time to waste standing in a corner filled with shame.

He had work to do. And by the way, a quarter of a million people attended the march that has gone down as one of the greatest peaceful protests in history.

History remembers Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream speech,” but it’s pared down in the film.

At different times, different portions of the film, different versions of the film had longer versions of the speech, but Rustin is the story ”of the man who pulled it all together” and then helped clean up the trash after the crowds had gone.

Some have said that Bayard Rustin has been criminally unrecognized.

“Yeah, yeah,” said Wolfe, shaking his head.

“I mean, that’s history. That is what history does. History goes, ‘I’m going to notice you. I’m not going to notice you. I’m going to reward you.’ History can be very, very brutal. And so therefore, if we find the stories that need to be told, then it’s our responsibility to make sure they get told. But that’s what history does.”

Must Read Stories

Six Takeaways From British TV Festival: Strike Ripples, Commissioner Slowdowns & More

WGA On AMPTP’s Latest Contract Offer: “Neither Nothing, Nor Nearly Enough”

‘Dune: Part Two’ Deserts 2023 Slot; ‘LOTR: War Of The Rohirrim’ Pushed

Mug Shot Released After Arrest In Georgia On Charges Tied To 2020 Election

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article