‘He did everything right and still lost his life’: Furious widow of Derek Jacobs slams smart motorway scheme after coroner says fatal crash would not have happened ‘had there been a hard shoulder’

- Derek Jacobs was killed when his van was hit by a Ford Ka on the M1 in 2019

- Sally Jacobs refused to attend the inquest last week, despite waiting four years

Sally and Derek Jacobs met, as many young couples do, at a party.

It was June 2, 1953, and the church hall in Kingsbury, North-West London, was decked out with bunting and Union flags, trestle tables heaving with scones and cakes, as the whole neighbourhood came together to celebrate the late Queen’s Coronation — just as we shall do again for King Charles, in a few weeks’ time.

Sally, then 16, was unsteady in a new pair of grown-up high heels and, to her horror, found herself stepping on the fingers of a man who had appeared by her feet.

‘I looked down and he was there on the floor,’ she recalls. ‘Typical Derek, he was on his hands and knees cleaning up. I was terribly embarrassed, but so was he. We both said sorry.’

And promptly fell in love.

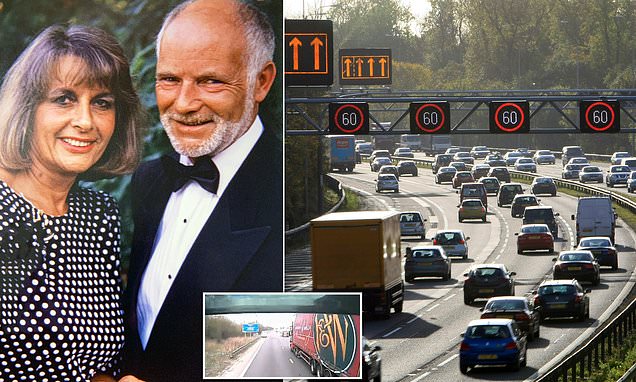

Since Derek Jacobs’ death in 2019, his wife, Sally Jacobs has been unable to mourn, instead channelling her energy into campaigning against smart motorways. Pictured: Derek Jacobs with wife Sally

Sally is furious, her ire directed at Chesterfield Coroners Court for failing to blame Derek’s death on the lack of hard shoulder

This is one of those gorgeous stories elderly couples, after a lifetime together, like to recount to anyone who cares to listen. Recalling fragments, still so vivid, of a time when they were young, their skin peachy, their hormones racing, when love found them and threw them together, for ever.

Sally remembers the ‘lovely, gingery fair hair’ of the 17-year-old youth at her feet, who, when he stood up, turned out to be ‘very short, but handsome’.

This should be the point where Derek chips in, with an anecdote of his own, recalling maybe those shapely ankles and their owner’s soft brown eyes. And how he plucked up the courage to invite her to a Scouts jamboree in Wembley the following week.

Only Derek can’t. One Friday lunchtime, in March 2019, on a stretch of the M1 just outside Sheffield, Derek, 83, was killed in a horrific crash.

Having suffered a burst tyre, he had steered his van as far over to the left as possible before grinding to a halt. The road was an ‘all lane running’ (ALR) smart motorway, meaning there was no hard shoulder, so he was forced to stop partially in the way of 70mph traffic.

He got out through the passenger door and, as he was about to climb over the barrier onto the verge, as government advice suggests, a car driven by Jean Scripps, then 77, smashed into his van, crushing Derek between the vehicle and the barrier, before careering into the middle lane and being hit by a coach.

Mrs Scripps’s husband Charles, 78, a passenger in her car, died two months later from his injuries.

Sally, now 86, refused to attend the inquest last week, despite having waited four years to find out the truth about what happened to her husband. Since his death, she has been unable to mourn, instead channelling her energy into campaigning against smart motorways and petitioning National Highways and the Department for Transport to reinstate hard shoulders on every major road.

A video shows the horrifying moment a car hits a van on a smart motorway before flipping over in the carriageway and ending up on its side in a crash which left two pensioners dead

The Mail, too, has been spearheading national opposition to these roads, highlighting evidence from whistleblowers and safety campaigners which show they put millions of drivers’ lives at risk.

Today, Sally is furious, her ire directed at Chesterfield Coroners Court for failing to blame Derek’s death on the lack of hard shoulder, and declining to make any recommendations to the authorities about the 400 miles of smart motorways still in operation.

‘If I’d been there, I would have screamed at the coroner,’ she says. ‘There is no doubt in my mind that Derek would not have died that day if he had been able to pull over on to the hard shoulder.

‘He did everything right and he still lost his life. I will treat the coroner, the Government and everyone else who is to blame for this with the contempt they deserve.’

Sally’s deep-rooted anger is at odds with her appearance: an elegant, soft-spoken woman with a neat, platinum bob.

‘The worst part,’ she says, ‘is the realisation that he will never come home. Some days I think I see him round the garden or coming in the front door.’

Derek, she says, ‘is in every brick in this house’. It’s the three-bedroom semi on the North London-Hertfordshire border, that they bought as newlyweds in 1958.

They’d saved up every penny from their jobs — Sally was a librarian and Derek an engineer, specialising in tool and pattern-making — to buy the property, and turn it into a family home.

Sally Jacobs, 85, holds a picture of her husband Derek during a segment on ITV news

‘Derek did everything himself — he was the most wonderful, talented man,’ Sally says. ‘He put in the central heating, did the tiling, landscaped the garden.’

When their two sons, Simon and Matthew, came along, Derek took easily to fatherhood. ‘My younger son said to me recently: ‘Mum, you forget — I haven’t just lost my dad, I’ve lost my best friend.’ ‘

Derek was a young soul, always smartly dressed and frequently mistaken for someone younger than his years. Though officially retired, he continued to work part‑time and loved the camaraderie with his colleagues.

He was a confident and competent driver; in 66 years, he’d never had so much as scrape or a speeding ticket. He was happily driving his white Volkswagen Crafter van up and down the country into his 80s.

When grandchildren — a boy, now 15, and a girl, 13 — arrived, Derek was besotted. ‘We used to take them on holiday and he would spoil them rotten,’ Sally recalls. ‘One day I told him off for spending so much money, and he said: ‘Let me spoil them while I can — I don’t know how long I’m going to be here.’ ‘

Indeed, the year before his death Derek was diagnosed with bladder cancer and underwent arduous treatment before being given the all-clear at Christmas 2018.

‘I clutched him in my arms and said: ‘I just couldn’t live without you,’ ‘ Sally says. ‘Little did I know I’d have to, three months later.’

The morning of his accident was no different to any other. Heading to Yorkshire for work, Derek kissed Sally goodbye, hopped into his VW van and drove off.

‘I said what I said every day: ‘Take care love, see you soon.’ ‘

His route took him along the M1, near the Derbyshire-Yorkshire border, a section of road which had been turned into a smart motorway as part of a £205 million ‘upgrade’ in 2016.

Smart motorways — rebranded ‘digital motorways’ in 2019 — have been in place in England since 2006, when a clogged-up stretch of the M42 in the West Midlands had its hard shoulder repurposed as a fourth ‘live’ lane.

The aim, according to Highways England — the government agency in charge of operating and improving motorways and major A-roads, now called National Highways — was to regulate traffic flow, ease congestion and minimise accidents.

There are three types: controlled, which have a hard shoulder but use variable speed limits to adjust traffic flow; dynamic, where the hard shoulder can be opened at peak times; and — the most controversial — ALR, where there’s no hard shoulder, only ’emergency refuge areas’, and drivers are alerted to incidents ahead on overhead digital screens.

The delay between incident and alert is supposed to be no more than three minutes, thanks to CCTV coverage and a supposedly high-tech radar system that warns highways staff about a broken-down vehicle within 20 seconds.

In Derek’s case, due to human error in passing on the alert — which came after a member of the public reported the stationary van, just 44 seconds after it had stopped — it took eight minutes for oncoming traffic to be notified of the obstruction. By then it was already too late; his van had been stationary for just over three-and-a-half minutes when it was struck.

Derek Jacobs, 83, was killed when his van was hit by the red Ford Ka on the M1 near Sheffield in March 2019 after he had stopped in the live inside lane and got out of the vehicle following a tyre blow-out

At the inquest last week, assistant coroner Susan Evans said it was ‘immediately apparent that, had there been a hard shoulder, this incident would not have occurred’. However, she added: ‘That said, there are many roads in the road network, including dual carriageway A-roads, that are subject to the national speed limit and do not have the benefit of any hard shoulder.’

Simon Boyle, the regional director for National Highways in Yorkshire and the North-East, told the inquest that the aim is for warning signs to be deployed within three minutes, and that the average in his region was two minutes and 15 seconds.

‘I don’t believe you can fully eradicate human error. Unfortunately, humans are operating and mistakes are going to be made,’ he said.

Mr Boyle added that the area has since been covered by technology to detect stationary vehicles.

Tragically, Derek’s is not the only death to have occurred on this type of road. Far from it.

The latest figures put the death toll on smart motorways at 79 — 28 of them on ALR motorways of the type Derek was driving on.

Read More: Harrowing video shows moment smart motorway crash killed two pensioners as inquest hears deaths would not have happened if there had been a hard shoulder

Data from National Highways itself shows an average fatality rate of 0.19 victims per hundred million vehicle miles — more than double the rate on conventional motorways.

Campaigners, including the lobby group Smart Motorways Kill — founded by widow Claire Mercer, whose husband, Jason, was killed on the same stretch of M1 as Derek, also in 2019 — have branded them ‘death traps’ and ‘ships without lifeboats’.

Some changes have been made. In response to a damning undercover investigation by this newspaper in 2021, which revealed inexcusable system failures, proposals to roll out 300 more miles of smart motorway by 2025 were postponed last year.

Reports last week suggest they may have been shelved.

But this, critics say, is far from enough. Smart motorways that are currently under construction will be completed; existing smart motorways will not have a hard shoulder reinstated; and safety targets designed to reduce the number of fatal crashes are still not being met.

For those whose lives have been destroyed and loved ones snatched away on these roads, there is no excuse for continued inaction.

Sally will never forget the night she was woken by her younger son, Matthew, to hear the worst news imaginable.

‘Derek was killed about midday — and it was midnight when the police got here to tell us,’ she recalls.

‘I’d said to Matthew earlier: ‘Daddy’s late, isn’t he?’ He always used to call when he was running later than planned.

‘We tried phoning him, but there was no answer. I knew in my mind that something awful had happened. Matthew had tried calling all the hospitals on his route.

‘My other son was tracking Derek’s van, but we couldn’t get a signal. It was just a horrifying time. I have nightmares about that knock on the door.’

Today, Matthew lives with her, helping out around the house as she becomes increasingly frail.

‘I don’t know what I’d do without him,’ she says. Her other son, Simon, lives 20 minutes away with his wife and children.

Sally supports the Mail’s campaigning against smart motorways and knows that, in talking about Derek, she is raising awareness of their dangers.

She hopes her words will not only force the Government’s hand, but will urge other drivers to be safe and vigilant when using them.

As for the other driver, Jean Scripps, whose husband Charles also died as a result of the crash, Sally bears her no ill will.

The coroner found that Mrs Scripps ‘appeared to have not been paying attention to the road’.

The inquest heard that Derek had pulled his van over so it was only protruding into the carriageway by about 65cm and that Ms Scripps could have passed it without going into the second lane. She was diagnosed with dementia six months after the accident.

‘I don’t feel any animosity towards her,’ Sally says. ‘It’s not my place to judge other people.’

‘We’d been together 66 years when he died. I’m sure I nagged and he did things that annoyed me, too, but we were so happy from the moment we met.’

There will be no fond memories at Coronation parties this year. Sally doesn’t know if she can bear to attend one without Derek.

He didn’t have a funeral; didn’t want one, Sally says. ‘He didn’t believe in all that fuss, or spending money on a big ceremony.’

Instead, there was a small family cremation — and when she got Derek’s ashes back, she planted them in a terracotta pot outside her kitchen door.

Growing there is a Japanese weeping acer, or maple tree. On warm days, when the sun streams into her kitchen, Sally props the door open with a chair, sits down with a cup of tea and talks to Derek, remembering happy times, such as the day they got a telegram from the Queen to mark their 60th wedding anniversary.

‘I turned to him and said: ‘We’ll make it to 70, won’t we, my love?’ And he looked at me and laughed.’

They so very nearly did.

Source: Read Full Article