Are the Germans already looking to ABANDON Ukraine? Huge protest this weekend – led by the far-Left and Kremlin apologists – will demand Berlin stops arming Kyiv… as polls show public support falling

- German far-left politician launched ‘manifesto for peace’ earlier this month

- Peace coalition has called on like-minded Germans to march this weekend

A huge protest organised for this weekend will demand that Germany stop arming Ukraine in its year-long fight against Vladimir Putin’s invasion.

Earlier this month, far-left politician Sahra Wagenknecht and feminist Alice Schwarzer launched what they called a ‘manifesto for peace’ criticising the government’s approach to the conflict.

Calling for ‘an end to the escalation of arms deliveries to Kyiv’ and ‘the opening of negotiations with Moscow’, they have also invited like-minded Germans to join them at a demonstration in central Berlin on Saturday. Russian apologists among the far-left and far-right fringes of Germany society are expected to attend.

As Berlin has increased its support for Ukraine since Chancellor Olaf Scholz took just days to announce seismic shifts in Germany’s military after Russia’s invasion, public support for sending arms in the middle-ground of German politics has also risen.

However, according to Ellen Ehn – editor in chief of Germany’s WDR TV, which runs polls on public opinion – the number of people who say Scholz’s decision to send main battle tanks to Ukraine was a mistake has started to increase.

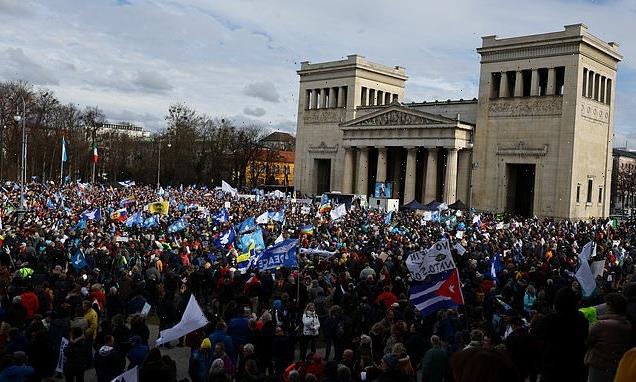

A huge protest organised for this weekend will demand that Germany stop arming Ukraine in its year-long fight against Vladimir Putin’s invasion. Pictured: People take part in an anti-war and Pro-Russian demonstration in Munich on February 18

While 44 percent said in a recent poll that Berlin’s support for Ukraine was ‘adequate,’ Ms Ehn on Thursday told BBC Radio 4’s Today Programme that 39 percent said it was a mistake to send tanks to Ukraine.

‘This is particularly the case in the east. East and West Germany are completely different,’ she told the programme. ‘People in the east generally say that diplomatic efforts don’t go far enough,’ she said, noting that many of those were at the extreme ends – the far left and the far right – in German politics.

Now, more than half a million Germans have signed a petition calling for a change in Berlin’s approach to Ukraine. It says rather than sending Kyiv more weapons, the country should instead insist on peace negotiations and a freeze in the conflict.

However, this could mean that Russia retains control of the vast swathes of Ukraine that it currently controls, an outcome that Kyiv considers to be unacceptable, and has vowed to push all of Putin’s forces out of the country.

Germany today is a different country to what it was a year ago.

Last year, Scholz announced that Germany would plough 100 billion euros into revamping the army, send weapons to Kyiv and wean itself off Russian energy.

But the Chancellor is finding himself struggling to put his ambitious plans into practice and to make them palatable to all in the country.

Wracked by guilt over the Holocaust, post-war Germany has always tread lightly on the world stage and pursued a pacifist approach when it came to conflicts.

Although Scholz has repeatedly said that Germany would lend Kyiv any necessary support in its bid to repel Russia, his decisions on sending heavy armaments from missile launchers to tanks only came after much agonising.

In his recent speeches, Scholz hints at what may be holding him back.

Ukrainian service members ride a BMP-1 infantry fighting vehicle, as Russia’s attack on Ukraine continues, near the frontline town of Vuhledar, Ukraine February 22, 2023

Pictured: Sahra Wagenknecht (centre), Bundestag faction leader of Die Linke leftist political party launched with feminist Alice Schwarzer what they called a ‘manifesto for peace’ criticising the government’s approach to the conflict

Calling for ‘an end to the escalation of arms deliveries to Kyiv’ and ‘the opening of negotiations with Moscow’, Wagenknecht and Schwarzer have also invited like-minded Germans to join them at a demonstration in central Berlin on Saturday. Pictured: A protester waves a Russian flag and coat of arms in Munich on February 18 at an anti-war, pro-Russian demonstration

Announcing his decision to send Leopard battle tanks to Ukraine, Scholz underlined in the Bundestag that ‘there are many citizens who are worried about such a decision and the dimension that it could bring’, as he urged them to trust him.

Not only are there fears of an escalation in the conflict, there are also many who remain reluctant to directly oppose Moscow. Others are wary of Germany’s new bid at re-arming itself or as a weapons supplier to Ukraine.

At the Munich Security Conference last weekend, thousands of protesters turned up in the southern German city to demonstrate against armament support for Kyiv.

Margot Käßmann, the former Bishop of Hannover, told the Today Programme that the peace coalitions goal of changing the debate over how Germany approach the war had been successful.

‘We now have an almost aggressive debate in Germany over whether we should deliver more and more weapons into the region of war, and what the manifesto really succeeded in – is brining a public debate which in the last two weeks was only about weapons that can we deliver to Ukraine,’ she told the BBC.

‘How many weapons, how many tanks, who goes first, who goes second. I think it’s a change in debate, and that’s what we wanted.’

She said that the coalition was calling for an end to the delivery of weapons ‘into an area of crisis of war’ and instead focus energy on ‘stopping the killing’.

Russia has been accused of war crimes against the people of Ukraine, killing thousands in indiscriminate shelling.

Kyiv and it’s allies say Putin’s invasion is an imperialistic land grab, while Moscow insists – among other excuses – it is for security.

Ms Käßmann did say that she was concerned about the more extreme far-left and far-right groups among the protesters expected to march in Berlin.

‘German peace society clearly says there’s no place for neo-Nazis or right-wing people – we don’t want them,’ she said. Therefore, she would not be attending the protest in Berlin, but would be at other events in the country.

Norbert Röttgen, who sits on the Bundestag foreign affairs committee and on the right of German politics, told the programme that he did not see the protests changing Germany’s approach to arming Ukraine.

The protests and petition were ‘representing a debate, and not more,’ he said. ‘And this is quite a natural thing for a democratic society. And there is strong, bi-partisan support for what the government is doing.

‘What is represented in these polls is that there is a fundamental shift in the attitudes and views to the German society. We were very pacifist society – this has fundamentally shifted,’ he said.

A protester wears a hat made of balloons, depicting a tank, as he takes part in an anti-war demonstration, during the Munich Security Conference in Munich, Germany February 18

Pictured: Protesters march down a street in Germany in support of Ukraine, in a counter-demonstration against pro-Russian demonstrators who were also marching in the city

On February 27, 2022, Scholz hailed a ‘new era’ as he announced the special fund for the military and vowed to meet NATO’s target of spending two percent of GDP on defence. Germany’s energy policies were also upended, throwing its export-orientated industry into chaos.

Before Russia’s invasion, Berlin was dependent on Moscow for 55 percent of its gas supplies and 35 percent of its oil.

The cheap Russian power supplies were welcomed by German industries as they helped keep costs low and, thereby, their exports competitive.

Gas has been a particular sticking point since Germany needs the fuel – less damaging to the environment than coal – to plug the gap left by the planned closure of its nuclear plants.

‘We thought it was a double dependency: yes, we were dependent on Russian deliveries, but we assumed that Russia was also dependent as a seller,’ Nikel said.

To make up for the missing supplies from Russia, Berlin has had to extend the life of its remaining nuclear plants by a few months, temporarily reactivate coal-fired power plants and open new liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals.

After months of scrambling for new energy sources, Scholz recently proudly proclaimed that Germany is now ‘independent from Russian gas’.

While the energy transition appeared to be going better than thought, on the military front, Berlin was struggling.

It was only in 1999 – under heavy pressure from NATO – when the German army joined the operation in Kosovo. Until then, Germany was happy to take on the mantle of Europe’s leading economic force, but not a military power.

Russia’s role as part of the allies that ended Adolf Hitler’s regime, and Germany’s recent history as country split between a capitalist West and a communist East for five decades before reunification in 1990 also led it to view Moscow through a different prism.

Last year, Scholz announced that Germany would plough 100 billion euros into revamping the army, send weapons to Kyiv and wean itself off Russian energy

Successive German leaders – from the centre-left Gerhard Schroeder to the centre-right Angela Merkel – pursued a path of dialogue and detente with Moscow.

Overhauling a military that had suffered from decades of under-investment was proving tough at a time when Germany is battling not only to renew its own military gear but also send huge quantities to Ukraine.

Scholz’s strong speech on the planned army revamp ‘has been relativised with time because it took too long for Germany to really back Ukraine including with military equipment and weapons,’ said Marie-Agnes Strack-Zimmermann of Scholz’s junior coalition partner the Greens.

‘In a crisis like this, you have to take responsibility courageously and not just react when the pressure increases in Germany and internationally,’ she told AFP.

Source: Read Full Article