Just William – The Christmas Truce: In a joyful conclusion to RICHMAL CROMPTON’S festive tale, her cunning anti-hero settles the score with his rival – with a little help from Santa

- Richmal Crompton first revealed character William Brown back in 1919

- Her first book called ‘Just William’ was published 100 years ago in 1922

- The title became synonymous with the 38-book series over next 40 years

In the first part of this story in yesterday’s Mail, the mothers of William and his arch-enemy Hubert agreed to put an end the boys’ rivalry by making them invite each other to their Christmas parties. But it all went terribly wrong when Hubert played a prank on William. Now The Outlaws plan their revenge…

They met in the old barn in the morning to arrange their plan of action, but none of them could think of any plan of action to arrange, and the meeting broke up gloomily at lunchtime, without having come to any decision at all.

William walked slowly and draggingly through the village on his way home. His mother had told him to stop at the baker’s with an order for her, and it was a sign of his intense depression that he remembered to do it.

In ordinary circumstances William forgot his mother’s messages in the village.

He entered the baker’s shop and stared around him resentfully.

It seemed to be full of people. He’d have to wait all night before anyone took any notice of him.

Just his luck, he reflected bitterly . . . Then he suddenly realised that the mountainous lady just in front of him was Mrs Lane.

She was talking in a loud voice to a friend.

‘Yes, Hubie’s party is this afternoon. We’re having William Brown and his friends. To put a stop to that silly quarrel that’s gone on so long, you know.

‘Hubie’s so lovable that I simply can’t think how anyone could quarrel with him. But, of course, it will be all right after today. We’re having a Father Christmas, you know.

‘Well?’ said Bates sharply, holding the door open a few inches. ‘What d’you want?’ William assumed an ingratiating smile, the smile of a boy who has every right to demand admittance to the cottage

‘Bates, our gardener, is going to be Father Christmas and give out presents. I’ve given Hubie three pounds to get some really nice presents for it to celebrate the ending of the feud.’

William waited his turn, gave his message, and went home for lunch. Immediately after lunch he made his way to Bates’s cottage.

It stood on the road at the end of the Lanes’ garden. One gate led from the garden to the road, and the other from the garden to the Lanes’ shrubbery.

Behind the cottage Bates’s treasured kitchen garden, and at the bottom was a little shed where he stored his apples.

The window of the shed had to be open for airing purposes, but Bates kept a sharp look out for his perpetual and inveterate enemies, boys.

William approached the cottage with great circumspection, looking anxiously around to be sure that none of the Hubert Laneites was in sight.

He had reckoned on the likelihood of their all being engaged in preparation for the party.

He opened the gate, walked up the path and knocked at the door, standing poised on one foot ready to turn to flee should Bates, recognising him and remembering some of his former exploits in his kitchen garden, attack him on sight.

He heaved a sigh of relief, however, when Bates opened the door.

It was clear that Bates did not recognise him. He received him with an ungracious scowl, but that, William could see, was because he was a boy, not because he was the boy.

‘Well?’ said Bates sharply, holding the door open a few inches. ‘What d’you want?’ William assumed an ingratiating smile, the smile of a boy who has every right to demand admittance to the cottage.

‘I say,’ he said with a fairly good imitation of the Hubert Laneites’ most patronising manner, ‘you’ve got the Father Christmas things here, haven’t you?’

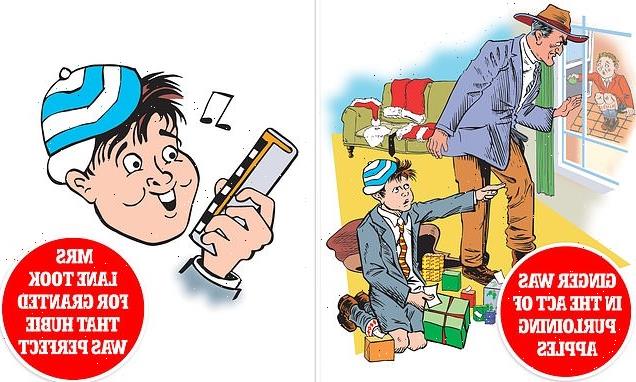

William entered, and threw a quick glance out of the window. Yes, Ginger was there, as they had arranged he should be, hovering near the shed where the apples were stored

The ungraciousness of Bates’s scowl did not relax, but he opened the door a few inches wider in a resigned fashion.

He had been pestered to death over the Father Christmas things. These boys had been in and out of his cottage all day with parcels and what not, trampling over his doorstep and ‘mussing up’ everything.

He’d decided some time ago that it wasn’t going to be worth the five shillings that Mrs Lane was giving him for it.

He took for granted that William was one of the Hubert Laneites coming once more to ‘muss up’ his bag of parcels, and take one out or put one in, or snigger over them as they’d been doing every day for the last week.

But he did think that they’d have left him in peace on the very afternoon of the party. ‘Yes,’ he said surlily, ‘I’ve got the things ’ere an’ they’re all right, so there’s no call to start upsettin’ of ’em again.

‘I’ve had enough of you comin’ in an’ mussin’ the place up.’ ‘I only wanted to count them, and make sure that we’ve got the right number,’ said William with an oily friendliness that was worthy of Hubert himself.

The man opened the door with a shrug. ‘All right,’ he said, ‘go in and count ’em. I tell you, I’m sick of the whole lot of you, I am. Mussin’ the place up.

‘Look at your boots!’ William looked at his boots, made an ineffectual attempt to wipe them on the mat and entered the cottage.

He had an exhilarating sense of danger and adventure as he entered. At any minute he might arouse the man’s suspicions.

His ignorance of where the presents were, for instance, when he was supposed to have been visiting them regularly, might give him away.

Moreover, a Hubert Laneite might arrive any minute and trap him in the cottage. It was, in short, a situation after William’s own heart.

The immediate danger of discovery was averted by Bates himself, who waved him irascibly into the back parlour, where the presents were evidently kept.

William entered, and threw a quick glance out of the window. Yes, Ginger was there, as they had arranged he should be, hovering near the shed where the apples were stored.

Then he looked round the room. A red cloak and hood and white beard were spread out on the sofa, and on the hearthrug lay a sackful of small parcels.

‘Well, count ’em for goodness’ sake an’ let’s get a bit of peace,’ said Bates more irritably than ever.

William fell on his knees and began to make a pretence of counting the parcels. Suddenly he looked up and gazed out of the window. ‘I say!’ he said.

‘There’s a boy taking your apples.’ Bates leapt to the window.

There, upon the roof of the shed, was Ginger, with an arm through the open window, obviously in the act of purloining apples and carefully exposing himself to view.

With a yell of fury Bates sprang to the door and down the path towards the shed. He had forgotten everything but this outrage upon his property.

Left alone, William turned his attention quickly to the sack. It contained parcels, each one labelled and named. He had to act quickly.

Bates had set off after Ginger, but he might return at any minute. Ginger’s instructions were to lure him on by keeping just out of reach, but Bates might tire of the chase before they’d gone a few yards, and, remembering his visitor, return to the cottage in order to prevent his ‘mussin’’ things up any more than necessary.

William had no time to investigate. He had to act solely upon his suspicions and his knowledge of the characters of Hubert and his friends.

Quickly he began to change the labels of the parcels, putting the one marked William on the one marked Hubert, and exchanging the labels of the Outlaand their supporters for those of the Hubert Laneites and their supporters.

Just as he was fastening the last one, Bates returned, hot and breathless. ‘Did you catch him?’ said William, secure in the knowledge that Ginger had outstripped Bates more times than any of them could remember.

‘Naw,’ said Mr Bates, panting and furious. ‘I’d like to wring his neck. I’d larn him if I got hold of him. Who was he? Did you see?’

‘He was about the same size as me,’ said William in the bright, eager tone of one who is trying to help, ‘or he may have been just a tiny bit smaller.’

Bates turned upon him, as if glad of the chance to vent his irascibility upon somebody.

‘Well, you clear out,’ he said. ‘I’ve had enough of you mussin’ the place up, an’ you can tell the others that they can keep away too.

An’ I’ll be glad when it’s over, I tell you. I’m sick of the lot of you.’ Smiling the patronising smile that he associated with the Hubert Laneites, William took a hurried departure, and ran home as quickly as he could.

He found his mother searching for him despairingly. ‘Oh, William, where have you been? You ought to have begun to get ready for the party hours ago.’

‘I’ve just been for a little walk,’ said William casually. ‘I’ll be ready in time all right.’ With the unwelcome aid of his mother, he was ready in time, spick and span and spruce and shining.

‘I’m so glad that you’re friends now and that that silly quarrel’s over,’ said Mrs Brown as she saw him off. ‘You feel much happier now that you’re friends, don’t you?’

William snorted sardonically, and set off down the road. The Hubert Laneites received the Outlaws with even more nauseous friendliness than they had shown at William’s house.

It was evident, however, from the way they sniggered and nudged each other that they had some plan prepared. William felt anxious.

Suppose that the plot they had so obviously prepared had nothing to do with the Father Christmas … Suppose that he had wasted his time and trouble that morning… They went into the hall after tea, and Mrs Lane said roguishly, ‘Now, boys, I’ve got a visitor for you.’

Immediately Bates, inadequately disguised as Father Christmas and looking fiercely resentful of the whole proceedings, entered with his sack.

The Hubert Laneites sniggered delightedly. This was evidently the crowning moment of the afternoon.

Bates took the parcels out one by one, announcing the name on each label. The first was William.

The Hubert Laneites watched him go up to receive it in paroxysms of silent mirth. William took it and opened it, wearing a sphinx-like expression.

It was the most magnificent mouth organ that he had ever seen. The mouths of the Hubert Laneites dropped open in horror and amazement. It was evidently the present that Hubert had destined for himself.

Bates called out Hubert’s name. Hubert, his mouth still hanging open with horror and amazement, went to receive his parcel.

It contained a short pencil with shield and rubber of the sort that can be purchased for a penny or twopence. He went back to his seat blinking.

He examined his label. It bore his name. He examined William’s label. It bore his name. There was no mistake about it.

William was thanking Mrs Lane effusively for his present. ‘Yes, dear,’ she was saying, ‘I’m so glad you like it. I haven’t had time to look at them but I told Hubie to get nice things.’

Hubert opened his mouth to protest, and then shut it again. He was beaten and he knew it.

He couldn’t very well tell his mother that he’d spent the bulk of the money on the presents for himself and his particular friends, and had spent only a few coppers on the Outlaws’ presents.

He couldn’t think what had happened. He’d been so sure that it would be all right.

The Outlaws would hardly have had the nerve publicly to object to their presents, and Mrs Lane was well meaning but conveniently short-sighted, and took for granted that everything that Hubie did was perfect.

Hubert sat staring at his pencil and blinking his eyes in incredulous horror. Meanwhile, the presentation was going on.

Bertie Franks’s present was a ruler that could not have cost more than a penny, and Ginger’s was a magnificent electric torch.

Bertie stared at the torch with an expression that would have done credit to a tragic mask, and Ginger hastened to establish his permanent right to his prize by going up to thank Mrs Lane for it.

‘Yes, it’s lovely, dear,’ she said. ‘I told Hubert to get nice things.’ Douglas’s present was a splendid penknife, and Henry’s a fountain pen, while the corresponding presents for the Hubert Laneites were an India-rubber and a notebook.

The Hubert Laneites watched their presents passing into the enemies’ hands with expressions of helpless agony.

The first story featuring schoolboy William Brown was published in a magazine in 1919, but it was the release of author Richmal Crompton’s first book about the 11-year-old schoolboy that sparked a phenomenon. Above: The cover of the first book; the image of Crompton that featured on the cover of her biography

But Douglas’s parcel had more than a penknife in it. It had a little bunch of imitation flowers with an India-rubber bulb attached and a tiny label, ‘Show this to William and press the rubber thing’.

Douglas took it to Hubert. Hubert knew it, of course, for he had bought it, but he was paralysed with horror at the whole situation.

‘Look, Hubert,’ said Douglas. A fountain of ink caught Hubert neatly in the eye. Douglas was all surprise and contrition.

‘I’m so sorry, Hubert,’ he said. ‘I’d no idea that it was going to do that. I’ve just got it out of my parcel and I’d no idea that it was going to do that. I’m so sorry, Mrs Lane, I’d no idea that it was going to do that.’

‘Of course you hadn’t, dear,’ said Mrs Lane. ‘It’s Hubie’s own fault for buying a thing like that. It’s very foolish of him indeed.’

Hubert wiped the ink out of his eyes and sputtered helplessly. Then William discovered that it was time to go.

‘Thank you so much for our lovely presents, Hubert,’ he said politely. ‘We’ve had a lovely time.’ And Hubert, under his mother’s eye, smiled a green and sickly smile.

The Outlaws marched triumphantly down the road, brandishing their spoils. William was playing on his mouth organ, Ginger was flashing his electric light, Henry waving his fountain pen, and Douglas slashing at the hedge with his penknife.

Occasionally they turned round to see if their enemies were pursuing them, in order to retrieve their treasures.

But the Hubert Laneites were too broken in spirit to enter into open hostilities just then.

As they walked, the Outlaws raised a wild and inharmonious paean of triumph. And over the telephone Mrs Lane was saying to Mrs Brown, ‘Yes, dear, it’s been a complete success.

They’re the greatest friends now. I’m sure it’s been a Christmas that they’ll remember all their lives.’

- Taken from William At Christmas by Richmal Crompton, published by Macmillan at £7.99. Cover by Adam Stower, story illustrations by Thomas Henry © Edward Ashbee and Catherine Massey 1995. To order a copy for £7.19 (offer valid until December 31, 2022; free P&P on orders over £20), visit mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937.

Source: Read Full Article