The Age’s opinion section is publishing a fresh series of summer pieces on the theme of ‘My Best, My First, My Worst’. These stories, penned by Age writers, range from humorous to poignant and thought-provoking tales of love, loss and summer fun. Read the collection here.

In December 2003, I had a job teaching English in southern China when the phone rang in my apartment as I was getting ready for work.

It was my parents ringing from Melbourne – much earlier in the morning than they normally called.

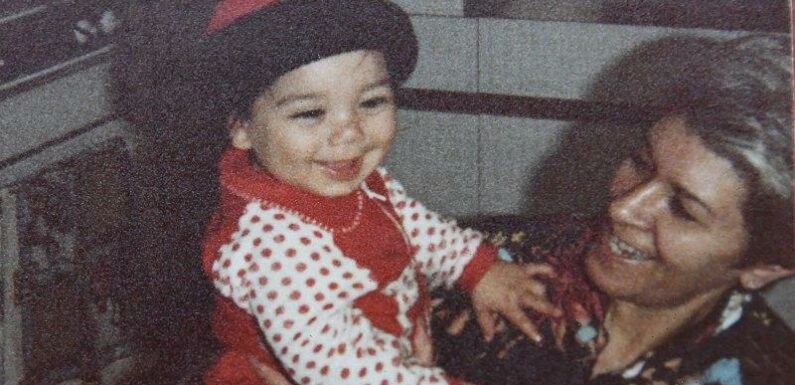

Hinda Preiss with her grandson Benjamin Preiss who is now an Age journalist.

They had been trying to reach me because my grandmother had suffered a bad fall while getting out of bed, and she had been taken to hospital from her nursing home.

Soon after, the phone rang again – my mother’s voice felt so distant as she gently told me it was all over. My grandmother, Hinda, had died.

I had been away from home for almost a year, backpacking around Asia – the closest thing I have experienced to unbridled freedom. I explored the Indian Himalayas and South-East Asia before landing a job in the Chinese city of Zhuhai, hoping to save money so I could continue travelling.

Yet, it was unimaginable that I would miss my grandmother’s funeral.

I took a ferry to Hong Kong and flew out of that restless metropolis and into the heat of the Melbourne summer, where I experienced profound loss and grief for the first time.

Hinda was the first of my grandparents to die. She was 76.

I remember little of the funeral service that summer afternoon, only fragments of my father’s speech.

But I can still conjure the sound of Hinda’s voice in our final conversation. I was travelling in India earlier that year when I called home during my family’s Passover dinner.

Hinda Preiss showering grandson Benjamin with attention.

My grandmother (“bubbe” in Yiddish) seized the phone and asked when I was coming back to Melbourne. A few months, I lied, knowing I planned to be away much longer.

“A few months?” she cried. “I don’t know if I’ll be alive that long.”

I told her the time would pass quickly, dismissing the despair in her voice. Anyone who knew Hinda well understood she was prone to dramatic statements.

There was a fierceness about her, and she was hardened by the circumstances of her life. She had evaded genocide in her Polish hometown of Łódź during the Holocaust by fleeing to Siberia with her family just as the war began.

She spent much of her teens chopping wood in freezing forests and staving off hunger while her people were murdered in her childhood home.

Hinda met my grandfather, Heniek, in a displaced persons camp in Austria after World War II, and she arrived in Melbourne heavily pregnant. By then she knew at least three languages fluently – Polish, Russian and Yiddish – but not yet English.

When she gave birth to my dad, Hinda could not even ask whether she’d had a boy or a girl.

She soon thrived in Melbourne, working from home sewing zips into jackets while her two sons were young and then as a machinist in garment factories to provide for the family of which she became the matriarch.

Bubbe Hinda was stubborn and unyielding in an argument.

Imagine trying to reason with someone who would end grandiose statements by asking: “Now tell me, am I right or am I right?”

But with me, her uncompromising will melted.

Bubbe lavished me and her three other grandchildren with lovingly cooked soul food, sweets and constant praise.

She bragged about our achievements – especially academic and musical – to anyone who would listen.

My brother and I slept over at her house every second Friday night until I was a teenager.

She would light the sabbath candles before we’d feast on chicken soup and dumplings, schnitzel and roast potatoes while watching Wheel of Fortune and Sale of the Century in the light of the flickering flames.

As we ate, she would whisper in Yiddish “ess, ess meyne kind” (eat, eat my child).

Hinda was a beautiful singer of Yiddish music – her voice unadorned but carrying the soul of the old country.

Even as a child I knew the songs she sang, food she cooked and Yiddish she spoke were the core of my cultural identity. They still are today.

When she died I lost a link to a Jewish world, destroyed before I had a chance to know it, yet somehow familiar.

After the funeral, my summer of 2003 lasted less than two weeks. I had always loved summers in Melbourne, but the city felt quieter and emptier without her.

I returned to winter in China to close the chapter on my time as an English teacher.

Now almost 20 years after she died, I still think of her every day.

Sometimes at night I go to bed hoping I’ll see Hinda in a dream.

I’ll introduce her to my wife and take her to meet my children, so she can see I’ve kept those candles burning.

I’ll tell her my children know Yiddish well. You can speak to them in our language, they understand.

If I have time before waking, I might even ask her if she’s proud of the life I’ve made and the family I created.

But really that would be unnecessary because I already know exactly what she’d say.

The Opinion newsletter is a weekly wrap of views that will challenge, champion and inform your own. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article