Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

The Australian Border Force is refusing to divulge how almost 100 foreign detainees will be electronically monitored after their release into the community by the High Court, leaving questions over how the federal government will keep watch over them.

Following new federal surveillance laws being passed last week, NSW and federal police are airing long-standing objections to being saddled with electronic monitoring duties, arguing that it eats up valuable resources.

Slain model and translator Altantuyaa Shaariibuu and her killer Sirul Azhar Umar, who is among the detainees being released.

Last week more than 90 people held in immigration centres were released into Australian communities after a High Court ruling found their indefinite detention was unlawful. Many have significant criminal histories, the government says.

Among the detainees is former Malaysian prime ministerial bodyguard, Sirul Azhar Umar, now released and living in Canberra. He was sentenced to death in his home country for the 2006 murder of a model, Altantuyaa Shaariibuu, but escaped to Australia and had been held in immigration detention.

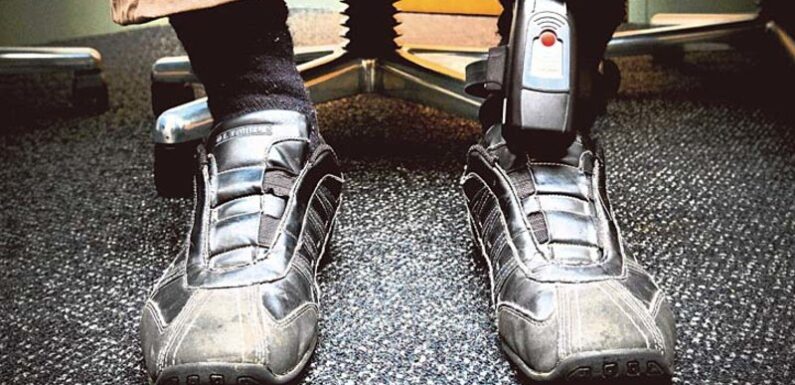

The federal government rushed through legislation – the Migration Amendment (Bridging Visa Conditions) Bill – which, among other things, required the released detainees to wear electronic monitors which track their location.

The Australian Border Force, which will oversee the program, will not reveal which agency will actually carry out the electronic monitoring, or what resources are required.

The government can’t say who will monitor electronic ankle bracelets on released detainees, a difficult task police have long resisted.

“The Australian Federal Police and Australian Border Force, through a joint operation, are working closely with state and territory authorities and law enforcement to further support community safety,” an ABF spokesman said in reply to questions asked by The Herald.

In NSW, the state government only keeps track of ankle monitors for people who on either parole or high-risk offender release orders. Monitoring is handled by a dedicated unit inside NSW Corrective Services because it is such intensive and expensive work.

NSW Corrective Services confirmed to The Herald they would only supply “equipment” to the ABF.

Private companies operate ankle monitors for people on bail in NSW. However, law enforcement agencies are highly critical, saying the private monitors do not protect the community and should not be used.

The most infamous alleged escape from an ankle monitor came later in 2021 when accused cocaine smuggler Mostafa Baluch allegedly cut off his ankle monitor and tried to flee NSW after being released on electronic bail.

Mostafa Baluch was on the run for more than two weeks then arrested at the Queensland border.Credit: NSW Police

He was captured two weeks later in the back of a truck travelling to Queensland, police said.

The ABF did not respond to questions about whether private companies were being considered to monitor detainees.

But AFP and NSW Police commanders, for years, have also attempted to dissuade courts from shouldering their agencies with the burdens of electronic monitoring.

“The AFP does not have any protocols or governance arrangements in place to provide instruction to AFP members on how to monitor, analyse or respond to electronic monitoring devices,” then-AFP Commander Stephen Dametto told a court in mid-2021.

“I am concerned the redirection of the AFP’s limited resources to monitoring electronic devices … would hinder the AFP’s ability to perform its statutory function and meet its strategic priorities.”

The Commander’s affidavit was written to oppose a bail bid by an accused ISIS supporter who offered to wear an ankle monitor supplied by a private company.

NSW Police Assistant Commissioner Stacey Maloney raised similar concerns, in the same 2021 court case.

“The NSW Police Force has no policy, capacity or staff allocated 24 hours a day to specifically monitor individuals on electronic bail,” Maloney wrote in her letter to the same court.

A NSW Police spokeswoman, when asked about the released detainees, said NSW Police do not monitor ankle bracelets. Police sources have told The Herald they are being tasked with house calls for the released detainees.

The AFP’s union said officers are being asked to help the government implement a “reactive policy” while already under-resourced and underpaid.

“Unless we get more resources, more people, better technology, what will we turn off?” AFP Association president Alex Caruana told the ABC on Monday.

“Counter-terror? Child exploitation? Organised crimes? Who will be short while AFP officers pick up this task?”

Dametto, in his 2021 letter, also shared concerns ankle monitors are “ineffective at identifying an imminent threat to the public”.

“The device would not deter a person carrying out an act of violence where that person also intends to martyr themselves,” he said.

The AFP Commander’s letter cites the case of Raghe Abdi who, in May 2019, cut off his bracelet and killed two elderly neighbours. Abdi was shot dead by police after pulling a knife and running toward them while screaming “Allahu Akbar”.

Another is accused drug importer Xu Lin, from Sydney, who cut off his ankle monitor and has remained at large since 2018.

The AFP had warned the courts they did not have the resources to monitor him, but the judge dismissed their concerns and released Lin on bail.

Spokespersons for Home Affairs Minister Clare O’Neil and Minister for Immigration, Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs Andrew Giles referred questions to the AFP.

The AFP are not commenting on their current role in operation AEGIS.

Cut through the noise of federal politics with news, views and expert analysis. Subscribers can sign up to our weekly Inside Politics newsletter.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article