Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

Academic and professional staff from five Victorian universities went on strike on Wednesday, cancelling lectures and tutorials and massing in Melbourne’s CBD in a co-ordinated push for higher pay and an end to the sector’s heavy reliance on casual labour.

Staff from the University of Melbourne brought Carlton traffic to a stop at midday as they marched from the Parkville campus to Trades Hall, joining striking workers who had been bussed in from Monash, Deakin, La Trobe and Federation universities.

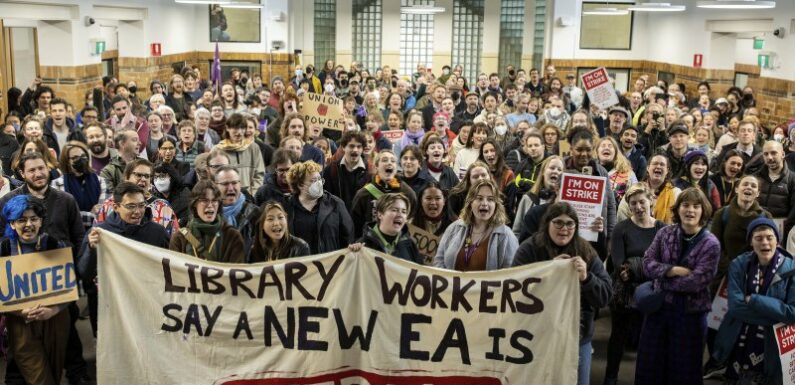

University of Melbourne staff and students gather for a four-hour strike over working conditions.Credit: Darrian Traynor

The stopwork action is part of a nationwide industrial campaign by the National Tertiary Education Union, with nine universities in Victoria, NSW and Queensland getting involved this week.

Monash staff voted for a 24-hour stop-work, beginning at 11am Wednesday, while Melbourne, Deakin and La Trobe staff went on strike for four hours, but voted to ramp up their campaign and potentially take open-ended strike action from June, unless the University of Melbourne improves its offer in bargaining for the next workplace agreement. Federation University staff are holding rolling stoppages across three campuses.

Addressing a crowd of several hundred staff and students crammed into a hall, University of Melbourne’s National Tertiary Education Union branch president David Gonzalez said the university had sent through a revised proposal last night in the months-long negotiation for a new agreement.

“This would not have happened if we did not call this strike action today,” Gonzalez said.

But he said the revised proposal did not come close to meeting the union’s list of demands.

“There is nothing in there about pay, there’s no target on secure employment, there’s nothing on working from home,” he said.

A key aim of the industrial action is to convince universities to include decasualisation provisions in their industrial agreements, as has been agreed at a handful of interstate universities, including the University of Sydney.

Universities are highly reliant on casual staff. The latest annual report for the University of Melbourne, for example, reveals that 52 per cent of its total staff last year were employed on fixed-term and casual contracts. At Monash the rate is even higher: 55.4 per cent.

A University of Melbourne spokesperson said the university was working constructively with the unions to reach a new enterprise agreement “that is fair to all … and one that positions the university for long-term sustainability and success”.

Victoria’s eight public universities reported 2022 deficits of a combined $507.6 million when their annual reports were published on Tuesday, as their finances continued to take a hit from lost international student revenue due to the pandemic.

University of Melbourne staff marching through Carlton as part of a strike involving four other universities.Credit: Darrian Traynor

The spokesperson said Melbourne University respected the rights of staff who choose to participate in industrial action, and those who do not. The university would work to reschedule any cancelled classes and anticipated that disruption to learning would be minimal.

First year arts students Grace Brewer and James Bonnyman were on campus when the strike began at 11am, and said that though they had only “baseline” knowledge of what their teachers were striking for, they supported their campaign.

Both students had classes cancelled or shortened on Wednesday due to the four-hour stoppage at Melbourne University.

“I think it’s really important. Both of my parents are teachers so I think it is something that should be supported,” Bonnyman said.

Some Monash University students did not have a tutor or lecturer when they turned up to class, as staff took a full day of protected industrial action.

The union’s Monash branch president, Dr Ben Eltham, said members had been told not to go on campus, not to notify the university that they wouldn’t be working and not to answer emails.

“Some classes won’t be taught. Some laboratories won’t be staffed, some libraries won’t be staffed,” he said.

“It’s across all faculties, across all work areas of the university. It’s a sprawling operation. There’s plenty of professional staff who are in the back office who are just as important as the frontline researchers and academics.”

Eltham said Monash University has made a formal pay offer of 4 per cent in the first year and 3 per cent thereafter.

“Members thought that wasn’t enough in the context of the cost of living crisis,” he said.

Staff are asking for an increase of CPI (consumer price index) plus 1.5 per cent, a reduction in workloads and the conversion of fixed-term to permanent staff.

High rates of casual employment also rankle.

“We have staff at Monash University who have been on rolling fixed-term contracts for 20 years. It doesn’t have to be like that,” Eltham said.

A Monash University spokesperson said the impact of the protected industrial action, to date, had been minimal.

The spokesperson said Monash acknowledged the right of NTEU members to engage in industrial action, but said that they had committed to providing more secure employment.

“Across 2022, 540 casual and sessional staff commenced in fixed-term and ongoing roles, through conversions, competitive and direct processes,” the spokesperson said.

“In addition, 227 fixed-term staff were moved to ongoing employment, including the transition of 85 research staff to continuing contingent positions. In 2023, the university will be offering current Monash PhD students 450 fixed-term roles this year.”

Deakin staff last week rejected a non-union offer from the university that would have granted them a 9 per cent salary increase over three years, with 62 per cent of staff who voted rejecting the attempt to bypass the union.

The union’s Deakin branch president, Dr Piper Rodd, said the four-hour stop work would disrupt teaching, but staff had voted strongly for industrial action.

“We are asking management to get back to the bargaining table straight away,” Rodd said.

“Our issues are that workloads are out of control and unsustainable; we want to see meaningful targets for decasualisation, 150 positions a year, which is not particularly extravagant and very doable.”

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article