By Matt Wade

Women wait for water to be distributed at the village of Lumayo in Somaliland. Water must be trucked to many communities because of drought.Credit:Jack Rintoul

Burao, Somaliland: An oversized red shirt covers Farhan Apti’s wasted body and pencil-thin arms. But his weak cry is enough to convey the horror of severe malnutrition.

The 16-month-old lies in his grandmother’s arms in a hospital at Burao in Somaliland, a self-governed region in northern Somalia.

He’s one of 1.5 million Somali children the UN says face malnutrition by the end of this month, as a humanitarian catastrophe engulfs the Horn of Africa.

Farhan Apti is nursed by his grandmother Arfi Jama at Burao General Hospital in Somaliland. The 17-month-old is being treated for malnutrition.Credit:Jack Rintoul

“Famine is at the door,” the United Nations emergency relief co-ordinator Martin Griffiths warned during a visit to Somalia last month. The world is “receiving a final warning”, he said.

The region’s worst drought in 40 years is driving the crisis – rains have failed for an unprecedented four consecutive seasons and weather forecasters predict that could extend to a fifth. The effects of drought have been compounded by disruptions to food exports, and food price volatility, caused by the war in Ukraine. More than 80 per cent of Somalia’s wheat imports come from Ukraine and Russia.

Millions of people across Somalia, Ethiopia and Kenya are on the move, searching for food and water. Small children such as Farhan are among the most vulnerable amid the upheaval. Weakened by a lack of nutritious food, he suffered a bout of measles followed by a chest infection, diarrhoea and vomiting. The boy had to be fed intravenously when first admitted to hospital.

Farhan’s 40-year-old grandmother Fardus Abdullahi blames the drought for his suffering.

“Getting food is difficult now, it is very expensive,” she says. “There is no milk in the village.”

In a hospital bed nearby, 17-month-old Amira Jimale lies silently, clutching at her ears. The skin on her shaved head and face is covered by dermatosis, a common symptom of severe malnutrition. Amira, who has been paralysed in both legs since birth, weighed just 5.5 kilograms when she was admitted, about half the normal weight for a girl her age.

“I’ve been sitting here for the last 14 nights worrying about her,” says her grandmother Arfi Jama.

Amira Jimale is 17 months old and is receiving treatment for malnutrition at Burao General Hosplital in Somaliland.Credit:Jack Rintoul

The crowded ward for malnourished children at Burao hospital is a simple stone building with whitewashed walls. A chart on the wall reflects the growing scale of the hunger crisis – new admissions have trebled since January.

The UN World Food Programme says up to 20 million people in the Horn of Africa region are at risk of starvation by the end of this year.

I travelled with a team from aid agency World Vision to meet Somalis caught up in the emergency. Poor road infrastructure makes it difficult to reach affected villages and camps. We spent long days driving on sandy tracks, sometimes barely navigable by four-wheel drive.

Because security is a problem in many parts of Somalia, our convoy was accompanied by an armed escort, front and back.

Matt Wade with the World Vision convoy and armed escort in Somaliland.Credit:Matt Wade

Graham Strong, World Vision Australia’s chief of field impact, who also visited Somaliland, says the suffering in the Horn of Africa region is the worst he has seen in 25 years of humanitarian work.

“Make no mistake, the levels of starvation sweeping across communities in Africa are the greatest of our lifetime,” he said.

The increasing frequency of droughts in the Horn of Africa has stoked concerns that climate change is affecting the seasonal rains that millions of farmers rely on. This is the third major food emergency in the region since 2011.

The UN says the severity of the Horn of Africa drought “underlines the vulnerability of the region to climate-related risks, which are expected to intensify because of climate change”.

Many Somalis uprooted by droughts in 2011 and 2017 are still living in camps for the internally displaced. Now a new wave of families is joining them, having been driven from their land and livelihoods by the lack of rain. But they are arriving at villages and towns already lacking sufficient food and water.

The director of World Vision in Somalia, Kevin Mackey, says the traditional coping strategies that families and communities use to survive during droughts have been exhausted.

“Since the beginning of 2021, a million new people have been displaced, which has almost doubled the number of internally displaced people in Somalia,” Mackey says.

One of them is Nimo Ibrahim, who two months ago migrated to a camp for the internally displaced at Khaatumo village, near Somaliland’s border with Ethiopia. Before the drought, Nimo’s family had more than 200 goats, but only a few remain.

I met Nimo as she sewed together pieces of old cloth into a tarpaulin to drape over the roof of her hut to provide better shade for her children from the fierce sun.

Mother-of-four Nimo Ibrahim sews pieces of old cloth into a tarpaulin to drape over the roof of her hut at a camp for displaced people in Somaliland.Credit:Jack Rintoul

“The drought has not yet killed us as a people, but it has taken everything we had,” she says.

Nimo’s husband has gone to the city of Hargesia searching for work, leaving her and their four children in the makeshift camp. With virtually all the family’s animals gone, she sees little prospect of returning to pastoral life.

“It seems we’ll be in this camp now,” she says.

Conditions are especially bad in parts of southern and central Somalia where prolonged civil conflict has limited the capacity of aid organisations such as World Vision to provide life-saving relief. The UN has warned that there are “concrete indications” that famine will occur in Somalia’s Baidoa and Burhakaba districts between October and December unless aid efforts are significantly stepped up.

Famine is formally declared when three awful benchmarks are reached: one in five households in a region must face extreme food shortage; more than 30 per cent of the population must be acutely malnourished; and at least two people in every 10,000 die each day.

Concern about mass starvation is also rising in Somaliland, the self-governing region in northern Somalia that has been relatively stable recently. About 80 per cent of Somaliland is already classified to have an “emergency” level of food insecurity.

Faisal Ali Mohamed, chairman of Somaliland’s National Disaster Preparedness and Food Reserve Authority (NADFOR), warns there is a likelihood of famine reaching some parts of Somaliland later this month unless seasonal rains arrive very soon.

“Our country is a semi-arid area,” he says. “But for years seasonal rains have failed in most areas, so the situation is very, very hard.”

Mohamed says international support for Somaliland’s relief efforts have been “very small” so far.

“We hope the international community, including Australia, will give directly to support our community.”

Barwayo Ali, a 19-year-old mother of two from the remote Somaliland village of Waraabeeye, is typical of those at risk. Soaring inflation has forced her to slash the amount of food she prepares. Milk is no longer available and her one-year-old son, Musab Muhamad, is now malnourished.

“Everything has gone up,” she says. “The price of some items, like cooking oil, has doubled, and when that happens you can’t get the same amount of food as before. Everybody here is worried about the future because of the drought.”

World Vision runs a mobile health clinic in Barwayo’s village. It identified that her son was underweight and is providing treatment. These health services have helped to keep the prevalence of severe malnutrition in the area relatively low.

Health workers run a mobile clinic at the village of Waraabeeye in Somaliland.Credit:Jack Rintoul

Vulnerable families also receive cash transfers from World Vision, so they can buy food and other provisions from local shops. Many recipients share the money received with relatives and neighbours. Water is being trucked to parched villages in the region.

One goal of these programs is to allow households affected by drought to stay in their homes rather than migrate to a camp for the internally displaced. Once families end up in camps, it is very difficult for them to restock their herds and return to pastoral production.

But humanitarian agencies warn that relief efforts in the Horn of Africa must be scaled up dramatically to prevent mass starvation and death.

Strong says Somalia is “not at the top of the world’s priority list” right now and emergency programs in the country are significantly underfunded.

“The worst of this crisis is ahead, much worse, which is why we must act now,” he says.

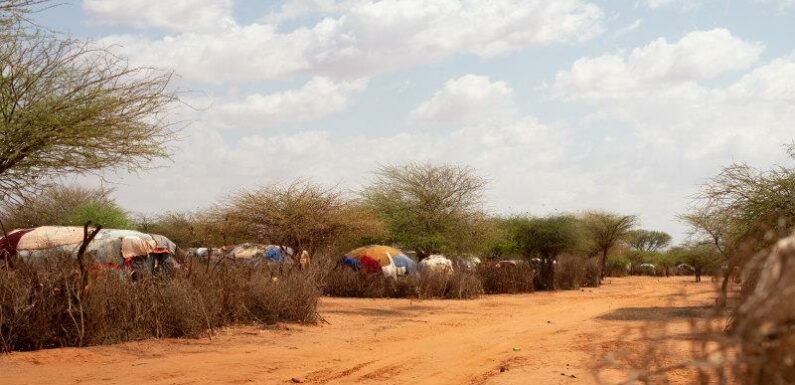

A camp for internally displaced people at Khaatumo in Somaliland.Credit:Jack Rintoul

This year’s global inflationary surge has hampered humanitarian operations by pushing up the cost of grain, fuel and other emergency supplies. The UN’s World Food Programme, the world’s largest humanitarian organisation, has been forced to cut rations in some places, so it can reach more people. “This is tantamount to taking from the hungry to feed the starving,” the WFP says.

Last month, Australia announced $15 million in emergency assistance to respond to the hunger crisis in the Horn of Africa region, but aid agencies say far more is required.

“This is a moment in history, of catastrophic need, and a moment in which Australia can stop children from dying,” Strong says. “We’ve done it before. We can do it again.”

The Help Fight Famine Alliance, a consortium of NGOs, is calling on the government to allocate $150 million to respond to the hunger crisis in this month’s federal budget.

If, as expected, famine is declared in parts of Somalia, funds provided by international donor nations are likely to scale up rapidly.

But that will be too late for many. The UN says 133,000 children died when Somalia last experienced famine in 2011. But according to some estimates, about half of them perished before famine was formally declared.

Matt Wade was supported by World Vision Australia to report from Somaliland. Donations can be made to World Vision Australia, Australian Red Cross, UNHCR and other international aid agencies.

Get a note directly from our foreign correspondents on what’s making headlines around the world. Sign up for the weekly What in the World newsletter here.

Most Viewed in World

Source: Read Full Article