Detroit: On her first day of high school, Andreya Thomas reviewed her schedule and found she was enrolled in a class with an unfamiliar name: JROTC.

She and other freshmen at Pershing High School in Detroit soon learnt they had been placed into the Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, a program funded by the US military designed to teach leadership skills, discipline and civic values – and open students’ eyes to the idea of a military career.

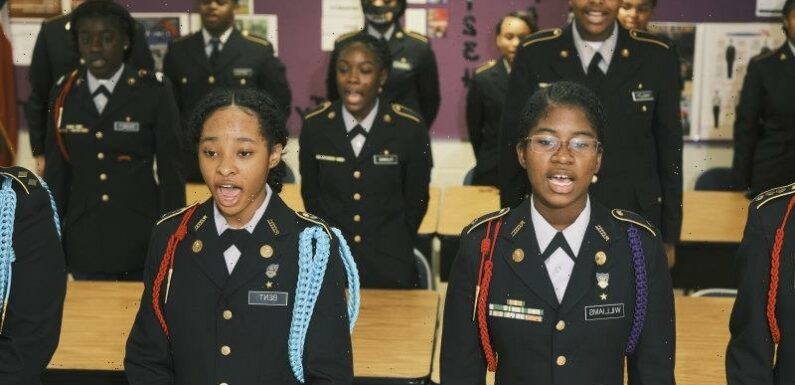

Students in JROTC recite the Cadet Creed at South Atlanta High School in Atlanta.Credit:Zack Wittman/The New York Times

In the class, students had to wear military uniforms and obey orders from an instructor who was often yelling, Thomas said, but when several of them pleaded to be allowed to drop the class, school administrators refused.

“They told us it was mandatory,” Thomas said.

JROTC programs, taught by military veterans at some 3500 high schools across the US, are supposed to be elective, and the Defence Department has said requiring students to take them goes against its guidelines. But The New York Times found thousands of public school students were being funnelled into the classes without ever having chosen them, either as an explicit requirement or by being automatically enrolled.

A review of enrolment data collected from more than 200 public records requests showed dozens of schools have made the program mandatory or steered more than 75 per cent of students in a single grade into the classes. A vast majority of the schools with those high enrolment numbers were attended by a large proportion of non-white students and those from low-income households, the Times found.

Andreya Thomas, who says she was told that her JROTC class in high school was mandatory, outside her dorm at Oakland University in Rochester, Michigan.Credit:Emily Elconin/The New York Times

The role of the program in high schools has been a point of debate since the program was founded more than a century ago. During the anti-war battles of the 1970s, protests over what was seen as an attempt to recruit high schoolers to serve in Vietnam prompted some school districts to restrict the program. Most schools gradually phased out any enrolment requirements.

But 50 years later, new conflicts are emerging, as parents in some cities say their children are being forced to put on military uniforms, obey a chain of command and recite patriotic declarations in classes they never wanted to take.

In Chicago, concerns raised by activists, news coverage and an inspector general’s report led the school district to backtrack this year on automatic program enrolments at several high schools that serve primarily lower-income neighbourhoods on the city’s South and West sides. In other places, the Times found, the practice continues, with students and parents sometimes rebuffed when they fight compulsory enrolment.

The classes, which offer instruction in a wide range of topics, including leadership, civic values, weapons handling and financial literacy, have provided the military with a valuable way to interact with teenagers at a time when it is facing its most serious recruiting challenge since the end of the Vietnam War.

Uniforms for the JROTC program at South Atlanta High School in AtlantaCredit:Zack Wittman/The New York Times

While Pentagon officials have long insisted the $US400-million-a-year ($590 million) program is not a recruiting tool, they have openly discussed expanding it. The Army says 44 per cent of all soldiers who entered its ranks recently came from a school that offered the program.

High school principals who have embraced the program say it motivates students who are struggling, teaches self-discipline to disruptive students and provides those who may feel isolated with a sense of camaraderie. It has found a welcome home in rural areas where the military has deep roots but also in urban centres where educators want to divert students away from drugs or violence and towards what for many can be a promising career or a college scholarship.

And military officials point to research indicating its students have better attendance and graduation rates, and fewer discipline problems at school.

Angelina Mejia and her father Julio, who says his daughter tried to get out of a required JROTC class when she was a freshman and was initially refused.Credit:Zack Wittman/The New York Times

But critics have long contended the program’s militaristic discipline emphasises obedience over independence and critical thinking. The program’s textbooks, the Times found, at times falsify or downplay the failings of the US government. And the program’s heavy concentration in schools with low-income and non-white students, some opponents said, helps propel such students into the military instead of encouraging other routes to college or jobs in the civilian economy.

“It’s hugely problematic,” said Jesús Palafox, who worked with the campaign against automatic enrolment in Chicago. Now 33, he said he had become concerned the program was “brainwashing” students after a JROTC instructor at his high school approached him and urged him to join the classes and enlist in the military.

“A lot of recruitment for these programs are happening in heavy communities of colour,” he said.

Schools also have a financial incentive to push students into the program. The military subsidises instructors’ salaries while requiring schools to maintain a certain level of enrolment to keep it going. In states that have allowed the training program to be used as an alternative graduation credit, some schools appear to have saved money by using the course as an alternative to hiring more teachers in subjects such as physical education or wellness.

Commodore Nicole Schwegman, a spokesperson for the Pentagon and a former JROTC student herself, said while the program helped the armed forces by introducing teenagers to the prospect of military service, it operated under the educational branch of the military, not the recruiting arm, and aimed to help teenagers become more effective students and more responsible adults.

“It’s really about teaching kids about service, teaching them about teamwork,” Schwegman said.

But she expressed concern about the Times′ findings on enrolment policies, saying the military did not ask high schools to make the program mandatory and that schools should not be requiring students to take it.

“Just like we are an all-volunteer military, this should be a volunteer program,” she said.

The program has always been heavily represented in regions like Texas and the Southeast, where the military has deeper roots and military families often proudly span generations. But even there, data released in response to federal, state and local public records requests showed some schools had relatively small enrolments.

Hillsborough County, Florida, for example, has made a major commitment to JROTC, with a program at every one of its high schools. But without enrolment mandates, the district averaged about 8 per cent of freshmen enrolled last year.

On the other hand, the Times’ review found a number of high schools where at least three-quarters of a grade’s students were enrolled in JROTC, including in Baton Rouge, Louisiana; Cape Coral, Florida; Charlotte, North Carolina; Memphis, Tennessee; Port Gibson, Mississippi; San Diego; Spring, Texas; and Vincent, Alabama.

Many other schools have more than half of all students in some grades enrolled in the program, including some in Atlanta, Baltimore, Boston, Dallas, Houston, Miami, St. Louis and Washington.

In analysing data released by the Army, the Times found that among schools where at least three-quarters of freshmen were enrolled in JROTC, more than 80 per cent of them had a student body composed primarily of Black or Hispanic students. That was a higher rate than other JROTC schools (more than 50 per cent of them had such a makeup) and US high schools without the programs (about 30 per cent).

In some districts examined by the Times, it was difficult to discern whether a school required JROTC or if some other reason had led a large percentage of its freshmen to enrol in the program.

In Detroit, the district said in a statement that administrators did not require students to take JROTC, although they “do encourage students in ninth grade to take the course to spark their interest.” But two recent students at Pershing, in addition to Thomas, said in interviews that they had been required to take the class. District data showed 90 per cent of freshmen were enrolled in JROTC during the 2021-22 school year.

Three other Detroit high schools also enrolled more than 75 per cent of their freshmen in the class, according to district data.

Schools that have faced questions over mandatory or automatic enrolments have often responded by backing away from the requirements, as Chicago did last year.

In that case, which came to light after an article from the education news website Chalkbeat, an investigation by the school district’s inspector general found that nearly 100 per cent of freshmen had been enrolled at four high schools that served primarily low-income students on the city’s South and West sides.

It was “a clear sign the program was not voluntary,” the report said.

At many schools, it said, freshman enrolment in JROTC “often operated like a prechecked box: students were automatically placed in JROTC and they had to get themselves removed from it if they did not want it. Sometimes this was possible; sometimes it was not.”

The district said in response that it was updating its parental consent process and making sure students had a choice between enrolling in JROTC or other, nonmilitary physical education classes.

In 2008, parents and other residents in San Diego confronted school district officials over concerns about forced enrolment and won what they believed was a promise by the district to ensure the program would be strictly optional. They also worked to eliminate the course’s air rifle programs in the schools.

But the Times’ review of data provided by the school district found there continued to be schools with high JROTC numbers, with 77 per cent of freshmen enrolled in the program at Kearny School of Biomedical Science and Technology last year. A district spokesperson said the data the district had provided had “some inaccuracies” but over the past several weeks did not provide new enrolment numbers and would not comment further.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Most Viewed in World

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article