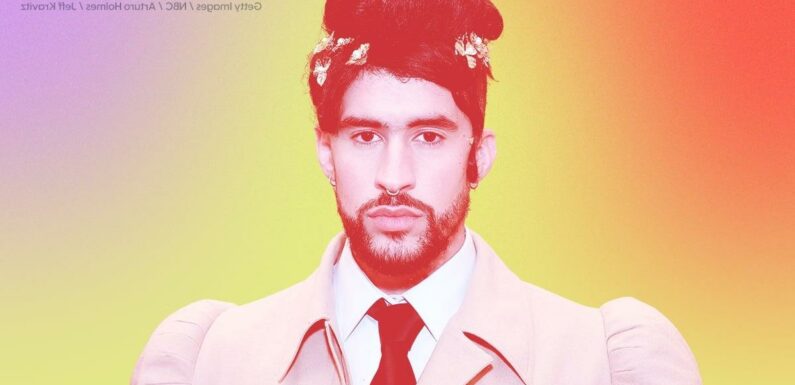

At this point, Bad Bunny’s gender fluidity is pretty much common knowledge. The rapper has made a career out of upending rigid gender constructs and transcending generationally held prejudices about what it means to be a man. So when he was announced as the VMAs’ artist of the year to a small crowd at my local bar, even the casual, non-Latinxs had some inkling of what the 28-year-old Puerto Rican artist has come to represent.

But rather than taking the stage to accept his award in the Spanglish that has become something of a trademark, Bad Bunny made us anticipate. The camera cut to Yankee Stadium, where thousands of fans waited in screaming anticipation for the artist. When Bad Bunny finally took the stage, it was through the open doors of a chapel, with an unknown bride in his arms. As the opening chords of his hit song “Tití Me Preguntó” played, he dropped his bride and picked up the mic, as if to acknowledge and subtly indict the heteronormative note on which the song’s video ended (for those who haven’t watched it, Bad marries a light-skinned, cis Latinx woman who descends from the heavens). By the time the song finished, he’d made out with two of his backup dancers — one a woman and the other a man. And I, along with most of the rest of the patrons at the bar, couldn’t help but smile. Because Bad just seems to do what he wants when he wants and brings the rest of the world screaming along with him.

No wonder his second album was titled “Yo Hago Lo Que Me Da La Gana.” Benito Martinez Ocasio, better known to the world as Bad Bunny, first came to my attention in 2016. A lifelong fan of Arcángel, I was intrigued by the light-skinned, tall kid with the bassy voice at the center of the “Tu No Vives Asi” video. It is a far cry from Bad’s more mainstream hits, depicting a side of Puerto Rico not often seen by outsiders. But even as he raps with bravado about “making holes in people’s faces” while ATVs do burnouts on project streets, the intangible air that would help Bad go from just another reggaetonero to a global phenomenon is already present. It’s in the often clumsy movements he doesn’t care to hide and effortless flow and voice that nestles subtle vulnerabilities in between cocksure rhymes. In a world of exaggerated swagger, hard lines, and finger guns, Bad refuses to take himself too seriously. And when challenging generationally held gender norms and prejudices, it’s an approach that has served him well.

Raised predominantly by a single mother, I often found myself straddling the lines between masculine and feminine that Bad disregards so casually. As often as my mother painted her nails, she would paint mine with clear nail polish. She would let me wear her jewelry (big cuff bracelets and bangles) and hand me down some of her power blazers and dress shirts (after removing the shoulder pads). But the older I got, the less acceptable these things became. Once I got to middle and later high school, I quickly realized that masculinity was currency.

This is the reality Latinx boys come of age in. While patriarchal ideologies can be found in almost every culture and ethnicity, ours is rooted in a normalized machismo that rigidly enforces gender roles and glorifies dominance or “alpha” behavior. Deviation from socially acceptable norms is discouraged through teasing, ostracizing, and sometimes violence.

And yet here we have Bad — wearing dresses, kissing men, and gracing the cover of Allure with domino-style acrylics and a cascade of rhinestone tears beneath his eye. And he does it in a genre that has historically propagated unhealthy attitudes about masculinity, pride, and honor. But how? Journalist and political activist Dr. Rosa Clemente thinks it’s a sign of the times. “This generation (millennials and Gen Z) is fed up with the old ways,” she tells POPSUGAR. “They’re questioning everything. [Saying] I don’t want to be a ‘she.’ I don’t want to be a ‘he.’ I want to be ‘they.’ I want to be ‘them.'”

For Dr. Clemente, Bad is representative of the ideals and values of his generation. And it makes sense. Artists have always been able to tap into the zeitgeist, from the revolutionary and antiwar songs of ’60s rock to the socially conscious bars of ’90s hip-hop. Today’s millennial and Gen Z artists represent a generation that has come of age in a globalized world where different perspectives are just clicks away. There are no givens. Gender, sexuality — it can all be challenged. But there’s another critical factor when it comes to Bad’s appeal, one that Dr. Clemente thinks is probably the most important.

“He’s authentic,” she says. Dr. Clemente points to one of his newer videos as evidence of this. “If you watch the video for ‘Titi Me Pregunto,’ in four minutes, it gives you his life story — our story, from the block in NYC to the bodegas, to the [Dominican presence]. It’s his life.” It is his life. One that shares aspects with what so many Latinx kids have experienced growing up. It’s the bodegas; the overbearing, nosey relatives; the block homies; the island. And this willingness to put himself out there, all of himself, is as crucial to his appeal as it is performative, with intention.

Today, the term “performative” has become shorthand for inauthentic. So it might seem contradictory to laud Bad Bunny for being authentic and then call his actions performative moments later. But when Bad performs wearing a skirt, or full-on switches genders like he does in the “Yo Perreo Sola” video, he understands the full reach of his platform and the power of his words and actions. In short, he knows the power of performance. He knew it when he rallied Puerto Ricans from all over the island to help oust our corrupt governor in 2019. He knew it when he wore a shirt saying “they killed Alexa” to bring awareness to the killing of Alexa Negron Luciano. And he knows it each time he performs the song “Andrea,” an homage to domestic-violence victim Andrea Ruiz. Bad Bunny knows the world is watching. And with each performance, he uses his time on stage to push boundaries and deconstruct the long-held idea of what it means to be a man.

No, he’s not perfect. During our conversation, Clemente is quick to point out that Bad’s version of reggaeton still embraces certain aspects of misogyny, particularly regarding how women are sexualized in some of his videos. But she also sees the big picture. “I’ve seen firsthand how powerful ‘art’ can be,” she says. “And even though it can be critiqued, what he’s doing is important. I mean, he’s not just the biggest star in the US. He’s the biggest star in the world.”

When I first heard Bad back in 2016, I didn’t know he’d go on to be the “biggest star in the world.” I just thought he made really good music. He still makes really good music. And when we talk about his boundary pushing and his trouncing of gender constructs, we have to remember that no one would be paying attention if the discography that supported the message was lacking in any way. Bad is a true artist. He can take the perreo of the early 2000s, mix it with ’70s salsa, and top it off with today’s trap to craft a sound that crosses generations in its appeal. He’s using that talent to move his genre in a more inclusive direction while at the same time staying true to himself.

Source: Read Full Article