More than 50 years have passed since Black Panthers Party co-founder Huey Newton entered an Oakland courtroom facing a murder charge, but his trial continues to influence the American legal system.

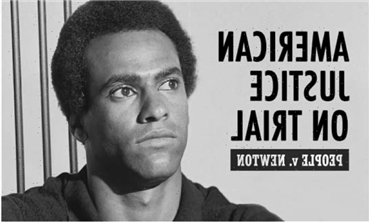

The impact of the sensational case comes into focus in the short documentary American Justice on Trial: People v. Newton, directed by Andrew Abrahams and Herb Ferrette, and written by Lise Pearlman (based on her book The Sky’s the Limit). It was produced by Abrahams and Pearlman. The film has earned a spot on the coveted Oscar shortlist despite lacking distribution.

Related Story

Fremantle's Spending Splurge Will Shoot Past $270M, Just Don't Say It's Fattening Up For A Sale

“When we think about great trials, we don’t think of this one,” Abrahams tells Deadline. “But when you start to look at it, it actually is.”

The film dials back to 1967 when police in Oakland pulled over a van in which Newton was riding. A dispute ensued and gunfire erupted, leaving officer John Frey dead, as well as another officer and Newton injured. Many observers, particularly conservative whites, considered it an open-and-shut case that would result in Newton’s conviction; Black Panther Party members and others sympathetic to Newton were convinced of his innocence, but doubted he could win acquittal.

The trial’s outcome would hinge on the strategy of defense attorney Charles Garry. Above all, he aimed to seat a panel of open-minded jurors.

“What the defense team led by Charles Garry did was basically challenge the systemic racism that was present in the court system and especially in the jury selection process,” Abrahams explains. “We were used to a jury of 12 white men, basically. And that really had not been challenged up until the time. What he did was bold and brave and also came with a lot of risk.”

During jury selection, Garry “was attacking potential jurors for their implicit biases, something that also hadn’t been done,” Abrahams adds. “It was bringing out into the open the issue of racism in terms of implicit biases and unconscious biases on the part of juries, the fact that there was little diversity on juries, the fact that it was much more difficult for Black jurors [to be seated].”

African American banker David Harper was chosen for the jury – the only person of color on the panel – and he became its foreman.

“David Harper was a breakthrough as far as even having someone [whose race] obviously parallels Huey,” Ferrette comments. “[That] was different. It was never done before.”

“[Harper] was really interested in justice and he took his job, his civic duty really seriously,” Abrahams notes. “David Harper did not assume that [Newton] was innocent… He wanted Newton to have due process and see where things landed based on the evidence and what was able to be presented in court.”

Judge Monroe Friedman presided. Newton took the stand and the judge gave him exceptionally wide latitude to articulate his defense.

“He allowed Huey to give a class… on racial [history in America],” Ferrette says, “to be able to bring that to the present, to be able to make that more public.”

“The whole issue of the 400 years of racism was something that the judge allowed,” Abrahams adds. “In most courts, it would not be allowed.”

“Especially in the ‘60s. Are you kidding?” exclaims Ferrette. “We can’t even think about it.”

The directors retained voice actors to bring the court transcripts to life. Cameras were not permitted in court at the time; with no courtroom footage available, Abrahams and Ferrette hired a sketch artist to render scenes.

“To do recreations or, as we originally were thinking, to do animation was expensive, and without the funding that comes to independent producers, budget is an issue,” Ferrette says. “The sketch artwork, even though it was quite a bit of money, it was less than what it would have cost [for another approach].”

Testimony in the trial mitigated the perception some people held that Newton had acted in cold blood. For instance, it came out that the initial bullet that hit officer Frey was fired by his fellow officer. In the end, the jury led by Harper returned a verdict of not guilty of first-degree murder, but found Newton guilty of voluntary manslaughter. In 1970 the conviction was tossed out and two retrials resulted in hung juries.

The original trial changed the way jury selection is conducted across America. The film itself is history-making.

“David Harper made a pact with the other jurors not to speak about the trial in public for 20 years,” Abrahams says. “This really is the first time that the jurors have talked about the trial in any significant way.”

Abrahams has made the Oscar shortlist before, with his 2008 feature documentary Under Our Skin. Achieving that distinction with American Justice on Trial came as a surprise because of the truly independent nature of the production.

“We’re one of one or two [shortlisted shorts] that are not repped by a major studio or wasn’t produced or is being distributed by a studio,” Abrahams says. “We didn’t have the marketing money to put into it. I like to think because of the merits of the film, it got us to where we are.”

He adds, “We will be distributing it educationally. We think this has a good a good place in the education market. We want to use it for universities and law schools and law firms. In terms of broader distribution, we don’t have a deal yet. Maybe that’ll change if we get a nomination.”

Must Read Stories

The Story Of Fremantle’s 2-Year, $270M Spending Spree: “They’ve Gone On A Mad One”

‘Everything Everywhere’ Wins Best Pic; ‘Better Call Saul’ Tops TV

Italian Cinema Icon Gina Lollobrigida Dies At 95; Played Esmeralda In ‘Hunchback’

Cieply: C’mon Voters, The Oscars Could Use A Little Sequel-itis

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article