Abercrombie & Fitch still smells faintly of “Fierce” cologne as you round the corner in the mall and approach the storefront. The logo is still inscribed in the same serif typeface, boldly welcoming the customer into the club and assuring them this is where they want to be and this is what they should wear.

These were my first observations as I apprehensively embarked on an intimate shopping experience at the Paramus, NJ, outpost recently, where the store manager promised I would be introduced to the new A&F. Of course, I can still recall my love/hate relationship with the old one. As a teenager struggling to embrace my rapidly-changing body, the size exclusivity used to send the message that I did not belong in A&F’s world. I remember watching my friend slip her legs into the same A&F jeans I had bought and feeling jealous that hers were three sizes smaller. It was a reminder that I didn’t look like her or the models in the ad campaigns.

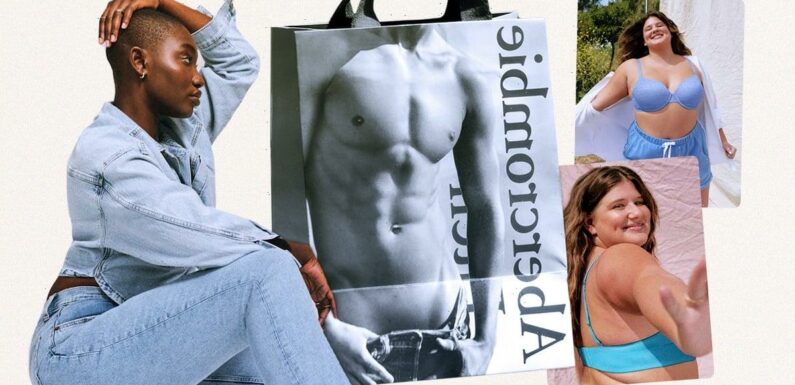

At school, my thighs would press through the rips in my A&F denim as if trying to break free. I’d push my skin back into the holes or adjust my position out of fear of looking chubby. “You don’t have to buy the jeans with rips,” my mom offered as a solution. But I did anyway, because I felt I was supposed to. In the early aughts, Abercrombie sold a singular image of thin, white, and cool, and customers were either erased completely or expected to conform. That sense of exclusivity has been unwavering since 1992, when former A&F CEO Mike Jeffries came up with a marketing plan that catered to white elitism, not unlike that of lingerie giant Victoria’s Secret’s at the time.

Two documentaries released last year — “White Hot: The Rise & Fall of Abercrombie & Fitch” and Hulu’s “Victoria’s Secret: Angels and Demons” — shed light on the problematic past of two renowned mall brands that soared to popularity in the early 2000s. While these companies are currently attempting rebrands to appeal to a more diverse customer base, many millennial shoppers still have an underlying connection to the early iteration of these stores, just like me. Bearing in mind that VS and A&F were, for many years, centering young, thin, white Americans, I wanted to test the waters to see how I felt walking into the stores today, in a mall setting. Would it be both familiar and uncomfortable all at once? Would I still feel so intimidated?

“Candidly, we go after the cool kids,” Jeffries infamously said in a 2006 Salon interview. “We go after the attractive all-American kid with a great attitude and a lot of friends. A lot of people don’t belong [in our clothes], and they can’t belong. Are we exclusionary? Absolutely. Those companies that are in trouble are trying to target everybody: young, old, fat, skinny. But then you become totally vanilla. You don’t alienate anybody, but you don’t excite anybody, either.”

Ostensibly, a lot has changed in the decade and a half since. A&F can now be seen as a “TikTok-friendly” label, with CEO Fran Horowitz at the helm since 2017. VS, meanwhile, launched VS Collective, a platform that centers women from diverse backgrounds who show progressive leadership in their fields.

Still, the in-person shopping experience at VS in particular remains fairly unchanged from that of the early 2000s. Meanwhile, A&F has installed more of an innovative overhaul in-stores, establishing an altogether different presentation than you’d recall from the early aughts. But whether or not these brands will ever feel quite as influential to the younger generation as they once were for millennials is worth examining. Does Gen-Z have the same emotional connection to mall brands? And, no matter how much these brands progress, will millennials ever let go of their stigma?

How A&F Became Synonymous With Scandal

Abercrombie & Fitch clearly left a mark on me, but on a broader scale, the corporation became known for discreditable behavior after a long series of shocking incidents.

Back in 1992, Jeffries was tasked with reinventing A&F when it was formerly owned by L Brands. It was during this time that the label became synonymous with offensive company culture and racism — and a slew of protests and lawsuits followed. In 2002, the brand produced anti-Asian T-shirts that were subsequently pulled from stores — after Asian American college students and advocacy organizations held protests.

Phil Yu, who runs the Angry Asian Man blog, was featured in “White Hot” to discuss the shirts and their impact. Upon being told there was at least one Asian designer who approved the designs, Yu said, “I feel like you just dropped a bomb on me,” continuing, “Your cover is the one Asian guy in the room who they ask, ‘Do you find it offensive?’ . . . Is he going to flip over the table and be like, ‘No, I think this is really offensive to my identity’? In that environment, in this corporate, stuffy environment where everybody around you is white, he’s going to be like, ‘I don’t know if this is really a safe place to do that.'”

The scandals kept coming, solidifying a sense that the brand was perpetuating entrenched racism. In 2003, former A&F employee Dr. Anthony Ocampo charged the company with a discrimination lawsuit titled Gonzalez v. Abercrombie & Fitch Stores, in which he and other plaintiffs alleged that they were refused jobs, terminated based on their race, or given responsibilities that kept them out of public view within stores. (In November 2004, a settlement was reached, winning $40 million dollars for rejected applicants and requiring the company to start various diversity-promoting initiatives.)

Source: Read Full Article