By David Free

What other kind of book is in such vibrant good shape? Credit: Jennifer Soo

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

Name one facet of Australian culture that has unquestionably improved over the last 50 years. Movies? TV? Popular music? Literary fiction?

You could argue, if you wanted to, that some or all of these things are better than they used to be. But in each case the claim would be debatable, as such claims generally are. Cultural judgments are nearly always a matter of opinion, not of objective fact.

But I think there’s one element of our culture that is measurably, and irrefutably, better than it’s ever been. Food. What serious human being would claim that food was better 50 years ago than it is now?

When I say food, I mean everything to do with food. I mean the range of ingredients available in delis and supermarkets. I mean home cooking. I mean pub food, club food, café food and restaurant food. I even mean takeaway food.

You can buy them secondhand. You can wait for the paperback, or opt for the digital version.Credit: Aresna Villanueva

At the heart of all this opulence is the cookbook. What other kind of book is in such vibrant good shape? When moving house not long ago, I was obliged to throw out a lot of books. My cookbooks, I found, were the volumes I was least ready to part with. My copy of Little Dorrit could easily go. I can always get another one, if I want to read the book again.

Cookbooks are less replaceable. After a while, a favourite cookbook becomes a sacred object – a book of memories, a catalogue of our triumphs and fiascos, a battle-scarred relic of kitchens and houses past.

And here’s another thing I’ve found about cookbooks. They’re the one kind of book I’m still willing to pay top dollar for. With other books you can skimp. You can buy them secondhand. You can wait for the paperback, or opt for the digital version.

You can’t do that with cookbooks. Kindle cookbooks are a waste of money. They strip away the visual and tactile glories of the three-dimensional work. Secondhand cookbooks are out for hygienic reasons. Much as I love the sensual attractions of a good cookbook, I draw the line at wanting to scratch and sniff the petrified gravy stains of the book’s previous owner.

A favourite cookbook becomes a sacred object – a catalogue of our triumphs and fiascos, a battle-scarred relic of kitchens and houses past.

No: cookbooks must be bought brand-new, in hardcover if possible. They must be leafed through and chosen in an actual bookshop. I can’t remember the last time I coughed up 50 bucks for a new work of fiction. For a decent cookbook, 50 bucks still feels like a sound investment.

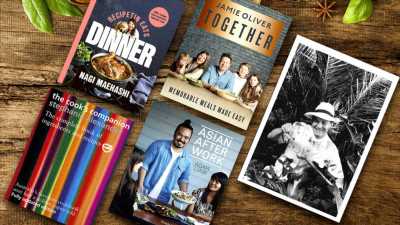

Apparently many other people feel the same way. Witness the success of Nagi Maehashi’s cookbook Dinner. Since its publication last October, Dinner has broken all sorts of records. It was the best-selling non-fiction book in Australia last year. It’s sold more units here than any other cookbook this century. It’s the most successful debut work by an Australian author of any stripe.

Cook books are the one kind of book I’m still willing to pay top dollar for.

In a way, the book’s popularity seems counter-intuitive. Nagi rose to fame as an online chef. On her website, RecipeTin Eats, you can get around 1200 recipes for free, including several of the recipes published in Dinner.

And yet people are still buying her book. They want to have and hold the magnificently heavy physical object, which brims with lavishly photographed recipes from all parts of the world.

Cookbooks weren’t always so sumptuous. I still have a few of my mother’s cookbooks from the 1960s and ’70s. I’ve kept these for sentimental reasons, not culinary ones. There’s nothing in them I would ever want to cook.

The oldest surviving cookbook from my mother’s collection is Step by Step Cookery (1963), by the prolific British food writer Marguerite Patten. In the 1950s, Patten hosted a BBC show called Cookery Club. She was one of the first TV chefs, and modern foodies like Nigel Slater have hailed her as a pioneer.

Nagi Maehashi of RecipeTin Eats. Her cookbook Dinner has broken all sorts of records.Credit: James Brickwood

Step by Step Cookery, which was published in association with the Australian Women’s Weekly, is a spartan work by today’s standards. It contains six glossy “plates” of colour pictures, but all the other photos are in unappetising black and white.

One of Patten’s recipes is for jugged hare. “Ask the shop to joint hare and give you the blood if available,” Patten writes. “Cook liver separately and if possible sieve and add to liquid with a little port wine and the blood.”

If you’re not into sieved hare’s liver, there is an adjacent recipe for boiled rabbit. Chop up a rabbit, then throw it in a pot with some parsley, bacon and root vegetables. Simmer in a pint of water until the rabbit is tender, then thicken the brew with some flour and milk.

In the 1960s, Australia still took its culinary cues from Britain. In several ways, this was regrettable. Post-war food rationing continued in Britain until the mid-1950s, and the after-effects lingered well into the ’60s. In books like Patten’s, the emphasis still lay on getting people fed with minimal fuss and expenditure. Indeed, Patten saw herself not as a chef, but a home economist.

Outside Britain and Australia, a world full of tastier cuisines beckoned. Writers like Elizabeth David were already urging Brits to try the delights of Italian and Mediterranean cooking. A revolution was waiting to happen: a Cambrian explosion of styles and flavours. But migration and globalisation hadn’t yet knocked down the walls.

Fortunately the revolution was underway by the early 1990s, when I began buying cookbooks of my own. One of them was the book that kick-started my adventures in serious cooking: Far-Flung Floyd (1993), by the British TV chef Keith Floyd.

Floyd was a new kind of TV chef. He didn’t just stand in a studio cooking stuff. He went to distant places and soaked up their cuisines. Far-Flung contained the fruits of his travels in South East Asia. I’d never heard of lemongrass until I bought Floyd’s book. I knew that lime trees had leaves, but I didn’t know you could eat them. Nor were such ingredients generally available in Australian supermarkets in the early 1990s, even in a major city.

Luke Nguyen: indispensable.

These days my shelves are full of indispensable cookbooks by Asian-Australian chefs like Luke Nguyen and Sujet Saenkham. But it was Floyd who got me started. He was an infectiously freewheeling cook. At the climax of his recipe for Dynamite Drunken Beef, he enjoined his readers to flame the wok with “a generous tot of whiskey.” Making the dish for the first time, I recklessly overdid the tot. The wok unleashed a Krakatoan shaft of fire that almost took my face off, and left a permanent scorch mark on the ceiling.

Although crammed with good recipes, Far-Flung Floyd was not, by current standards, a great-looking cookbook. But as the ’90s went on, cookbook design became an art form in itself. Stephanie Alexander’s The Cook’s Companion, first published in 1996, was as delicious to look at as it was to cook from.

The book is now rightly viewed as an Australian classic, and some of the recipes in it still strike me as definitive. When I roast a chook, or make beef bourguignon, I always do them Stephanie’s way. Why meddle with the classics?

In the foreword to his book Asian After Work, Adam Liaw says something profound about cookbooks. To get your money’s worth from one, you don’t have to try every single recipe in it. If a book can add just one or two meals to your repertoire, it’s already changed your life for the better.

Liaw’s own books prove the point. His latest, Tonight’s Dinner 2, helped get me out of a major cooking rut. I was spinning my wheels. I badly needed some new recipes to restoke my enthusiasm, and to remedy some of my self-imposed blind spots.

For example, I’ve always had a mental block about making my own pizza dough. I thought it was too much trouble. Liaw’s book cured me of this folly with a simple dough recipe that involves, in his words, “no rolling, no flour on the bench, no mess.” Thanks to those nine words, my own work in the pizza space has been revolutionised.

At this point I should probably mention that Liaw, like Nagi Maehashi, writes recipes for this masthead. This fact has no bearing on my enthusiasm for either author. I’d be praising them even if they wrote for the Daily Worker.

Back in 2010, Matthew Caldicott, Adam Liaw and Claire Winton Burn brace themselves in MasterChef.Credit: Channel Ten Publicity

The great cookbook writers are demystifiers. They know how to talk your language. Liaw may be a MasterChef winner, but he hates getting flour on his bench too. Jamie Oliver, the most beloved of the celebrity chefs, has a similar knack for imparting hard-won knowhow in user-friendly form. It isn’t just the big bold flavours that people buy his books for. It’s the down-to-earth hacks and tips.

Recently, Jamie was accused of committing the supposed sin of cultural appropriation. It was a fatuous charge. You could level it at any English cook who has ever dared to make something more exotic than jugged hare without obtaining written permission from the United Nations.

But because Jamie is the most conspicuously successful of the TV chefs, he’s the one who copped the heat. He responded by assuring the press that he now employs “teams of cultural appropriation specialists” to give his recipes the OK.

I’d have preferred it if he’d told these types to rack off. The idea that it’s a form of theft to absorb a cultural influence is always philistine, and nowhere is it more laughable than in the field of cookery. Everything about food culture is antithetical to the divisive spirit of identity politics. Every good cookbook is fuelled by a generous impulse to spread wisdom and happiness, and share delicious things.

The story of food culture over the past 50 years proves that life is not a zero-sum game. The barriers that used to separate our cuisines, denying us access to each other’s best ideas and tastiest techniques, have fallen.

The fact that some people would like to re-erect those barriers is one of the strangest of our current absurdities. But if we ever catch ourselves thinking that our culture has become terminally petty and joyless, we should take a break for lunch or dinner, and remind ourselves that there’s one department in which we’ve never had it so good.

To read more from Spectrum, visit our page here.

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from books editor Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.

Most Viewed in Culture

Source: Read Full Article