The militant group Boko Haram has been a dangerous and ubiquitous presence in Nigeria and its neighboring countries for many years. In “Le Spectre de Boko Haram,” Cameroonian filmmaker Cyrielle Raingou focuses on their presence in a small village in northern Cameroon, on the border with Nigeria. Her observational and gritty documentary registers the impact of Boko Haram’s actions on three school-age children, brothers Mohamed and Ibrahim and their classmate Falta. The nonfiction film is a clear-eyed look at how everyday life and the accompanying humdrum tasks go on despite the threat of violence at any moment.

The three children go to school, work at harvesting the fields and sometimes just skulk around like many children their age, avoiding anything serious. Menacing Boko Haram soldiers are omnipresent in the periphery with their big guns and large trucks, parading around in camouflage outfits. There’s a stark contrast between the brothers and Falta. She lives with her mother and siblings and the film follows that family dynamic. When she asks her mother to tell her how her father was killed by Boko Haram, the moment eerily recalls scenes seen in other movies where a child asks about how their parents met. It touches on the same notes of love and life, though here it includes death.

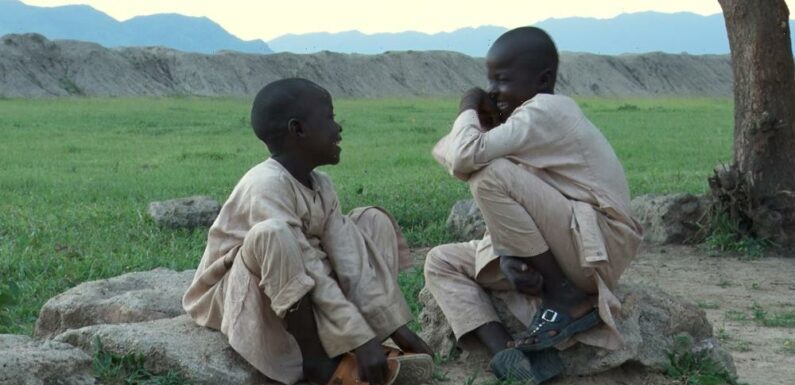

Mohamed and Ibrahim have been separated from their parents, and it’s never clear if there are any adults in their lives. The brothers, who are refugees in this village, laugh as they recall their encounters with Boko Haram soldiers. They talk about bombs, slit throats, even being whipped so disarmingly, the violence recedes for a moment. However, they can’t escape the melancholy that creeps in as they try to recount to each other how they got separated from their parents. Mohammed, the older, might know more than his younger brother, but he never tells, neither to his brother nor to the other people in the village who question him. Perhaps he saw somethin; perhaps he thinks they are on the wrong side of this conflict and saying anything resembling the truth might implicate him and his brother. Raingou’s rigorously observational methods perceptively show how the adults around them might be judging them.

As they spend more time in front of the cameras talking, the stories the brothers tell become more fanciful. Rooted in their reality at first with talk of soldiers and actual events that happened, it soon expands to include tall tales of witches turning into cats. The could be a child’s way of making sense of, or dealing with, the constant threat to life around them. Aware of the cameras at all times, sometimes they look straight into the lens, they could also be playing it up for the filmmakers. Whether this is their nature or an affectation for the cameras it adds up to a fascinating glimpse into their lives and coping mechanisms.

Unadorned and gritty, Raingou’s filmmaking has no embellishments. There are no musical cues to stir emotions, no fancy camera angles or fast edits to hammer home a point. The strength of the project comes from observing these children and the connections they make, or fail to make, with those around them. Their teacher Mr. Lamine tries to impart a sense of normalcy by being a taskmaster with school work. The differing ways in which Mohamed, Ibrahim and Falta react to that subtly shows their psychological state and how they are dealing with the situation.

As the film goes on, it becomes clear that Raingou cannot figure out an ending. The conflict still rages on. The environment Mohamed, Ibrahim and Falta live in, is still volatile. So the narrative feels incomplete, but that’s just the nature of existence in this part of the world. Things change suddenly, lives end suddenly or they can just go on as they are. At a brisk 81 minutes, Raingou manages to capture that juxtaposition and shine a light on part of the world that needs more attention.

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article