Editors note: William C. Rempel, a longtime journalist who has covered the Roman Polanski case, and Sam Wasson, author of The Big Goodbye about the making of Polanski’s Chinatown, successfully petitioned the courts to open long-sealed testimony last year. Continuing to monitor the case, they here describe the expected next steps.

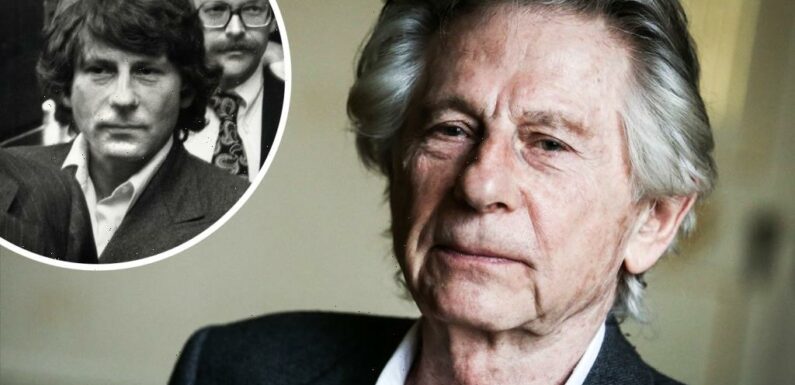

The real-life criminal case of Chinatown director Roman Polanski, a tale of dark secrets and perverted justice that has dragged on in Los Angeles Superior Court since the 1970s, will likely play its final scenes in a downtown courtroom soon – one way or another.

Related Story

French Indie Cinema Sector Calls For Revolution As Arthouse Box Office Slump Deepens

There are, however, a couple of plot lines still to be resolved in what began as a celebrity scandal in 1977 before turning into a legal morass that culminated in international embarrassment to the local judiciary.

Three factors are driving the case toward some sort of conclusion.

First, attorneys for the filmmaker who pled guilty to statutory rape nearly a half-century ago, are drafting fresh motions to reschedule his sentencing – this time in absentia.

Second, public release last summer of sealed evidence, notably pointing to judicial and prosecutorial misconduct, has already put the most sensitive secrets of the case on the record. Motives to hide the court’s dirty linens no longer matter.

Finally, time may simply run out on official interest in Polanski and his sentencing status. It seems no longer to be the priority of courts or law enforcement anywhere. The wanted man lives beyond extradition in France and a home in the Alps, and he continues to make movies. He will turn 90 in August.

The big cliffhanger in what’s left of this drama is whether revelations of past courthouse misconduct will force authorities in Los Angeles finally to drop a 45-year-old fugitive warrant against the Oscar winner. And, if so, is Polanski likely to receive some version of the controversial sentence once promised – and then reneged upon – by then-presiding judge, Laurence J. Rittenband?

Even the child victim, today a grandmother in her 50s and living in Hawaii, supports an end to the procedural nightmare that has made this case one of the longest-running legal tangles in California state court history.

It all started with a private photo shoot in Los Angeles in 1977 at which the 45-year-old Polanski lured the 13-year-old model into a hot tub, plied her with drugs and alcohol and engaged in sexual conduct for which she was too young to provide legal consent. He later apologized and agreed to plead guilty to statutory rape, the most serious of the charges brought against him.

While there was no guarantee of leniency at that time, Rittenband had told lawyers for the victim and both sides of the case that he was leaning that way.

After Polanski’s guilty plea, Rittenband sent him to Chino State Prison for the customary 90-day psychiatric evaluation typically required after convictions. And in the privacy of his closed-door office, the judge told lawyers his plan – subject to a favorable psych evaluation – was to make that 90-day detention the sum total of Polanski’s prison time.

By then, two separate probation officers had already interviewed Polanski and recommended “no incarceration.” One of the reports justifying a sentence of probation, noted that “the defendant… has demonstrated genuine remorse” and accepted responsibility.

The victim’s lawyer supported the idea, saying the young teen and her family wanted to avoid a trial and that they supported leniency for Polanski to achieve that.

The only objection was from Deputy District Attorney Roger Gunson. He complained that counting the 90-day diagnostic exam time as incarceration time was improper under the law. But Rittenband, who the prosecutor also called “a locomotive” that never changed direction once he made up his mind, waved off the prosecutor’s protest.

The deal was set – until negative press and public reaction erupted.

Rittenband’s sensitivity to criticism grew even more when the diagnostic exam lasted only 42 days. That’s when the “locomotive” changed his mind. He wanted Polanski to serve another 48 days – to equal his original 90-day sentence.

And then it got worse.

Rittenband, a 72-year-old veteran L.A. jurist, convened a presentencing session in his private chambers with all the lawyers. The meeting was off the record. No tape recorders or official stenographers were keeping notes when the judge disclosed his plan to impose a potentially more stringent sentence… but simply for public show.

He pledged to let Polanski out early, as promised, but away from cameras and reporters, once the filmmaker had completed a total of 90 days in jail. The judge asked only that Polanski trust him, and then set one more non-debatable condition:

The side deal had to be kept secret from the media. In other words: No one could rat him out to the press.

And then it got worse.

Rittenband assigned specific speaking roles for both lawyers to perform at a public sentencing hearing set for February 1978. Doug Dalton on defense would argue for probation … no prison time; Deputy D.A. Gunson would argue for a year in state prison; Rittenband would think about it and then sentence Polanski to “a term prescribed by law” – wink, wink – but then order his release without fanfare just 48 days later. The math: those 48 days tacked on to the 42 at Chino equaled 90 days in custody.

But then it got worse.

Defense lawyer Dalton not only declined to play along in any orchestrated charade, he threatened to demand a public hearing into the judge’s lies and cover-up scheme. Rittenband countered by threatening to retaliate – against Polanski – warning the lawyer he might keep his client in custody beyond the judge’s newly promised 48 days.

At that time in February of 1978, however, “a term prescribed by law” under the existing state legal codes left Polanski facing a potentially open-ended jail term ranging from two to 20 years – and theoretically up to 50 years. That revised deal required considerable trust in the word of a judge who, at that very same time, was breaking his previous promise.

Caught in this mish-mash of politics and justice, Polanski opted instead for a flight out of the country.

That was one of those rare moments in history when the prosecutor and his rival defense lawyer were driven to the same extreme: Separately, each drafted language for legal motions seeking Rittenband’s disqualification and removal from the case. Gunson’s superiors in the Los Angeles District Attorney’s office refused to authorize it.

But both Gunson and Dalton had come to the same conclusion: That while Polanski was not an innocent man, he was the victim of a dishonest judge. In a note of understated eloquence the prosecutor later called the difficult situation: “my dilemma.”

The intervening years have brought more bad news, both for Polanski and for the reputation of justice in Los Angeles.

Twice in the past 12 years the filmmaker has been arrested and held for extradition on that old fugitive warrant, successfully defending himself in both instances as “a fugitive from injustice.”

In 2010 in Switzerland he was jailed for two months – a period longer than the 48 days remaining under Rittenband’s interrupted sentence. He served an additional six months under house arrest before Switzerland denied extradition.

Five years later in Poland, where Polanski was attending the opening of a Jewish museum honoring victims of the Holocaust – among them his mother – he was briefly detained until Polish authorities also refused to extradite. A court in Krakow accused the Los Angeles court of actions that “flagrantly contradicted the fundamental principles of a fair trial.”

Eventually, the California Court of Appeal urged a review of sealed records in the Polanski case, saying: “We remain deeply concerned that these allegations of misconduct have not been addressed by a court… Polanski’s allegations urgently require full exploration and then, if indicated, curative action for the abuses alleged here.”

And that’s where the case remains today, though time has imposed other significant changes: Rittenband had already retired when he died at 88 in 1993. Dalton died at 92 last year. Meanwhile, successions of presiding judges and district attorneys have refused to close the case without Polanski’s personal appearance in a California courtroom. Polanski still refuses.

Longtime Los Angeles lawyer Harland Braun now represents the filmmaker. He advocates use of a technology unavailable when Polanski fled Rittenband’s jurisdiction.

“You know, they’ve invented something called Zoom. So, my client need not attend in person. And we all know now that Roman no longer owes any time under California laws.”

After all these years, could such a fraught case actually end in a Zoom call?

Of course, this is the more important question: Will a justice system that has strained for decades to keep damaging evidence secret finally acknowledge the dishonesty that its secrecy has been covering up for so long?

Must Read Stories

Sacha Baron Cohen & Keke Palmer Team For ‘Super Toys’; New Liam Neeson Pic; More

Alec Baldwin Sued For Negligence By Ukrainian Parents & Sister Of Halyna Hutchins

Harvey Weinstein Hit With New Rape Suit From L.A. Trial’s Jane Doe #1

Open To Hulu Sale; Peltz Drops Board Battle; Company Split Into 3 Units; Showbiz Chiefs Set

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article