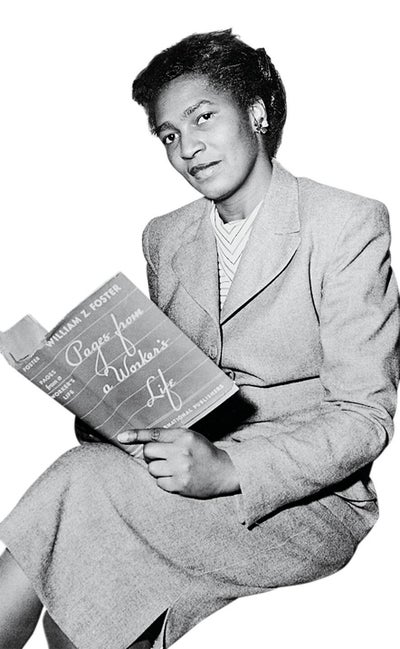

Dr. Charisse Burden-Stelly, colloquially known as Dr. CBS (and famously @blackleftaf on her prolific Twitter account), spoke to ESSENCE about the importance of Black August, her forthcoming coedited book, Organize, Fight, Win: Black Communist Women’s Political Writing, and the radical Black women whose legacies get sanitized.

ESSENCE: What are the origins of Black August?

CHARISSE BURDEN-STELLY: Black August emerged from the August 21 Coalitions, which were organized in the late 1970s to honor George Jackson, a political prisoner who was assassinated on August 21. It also served as tribute to his brother, Jonathan, who was murdered on August 7, 1970; and to Jeffrey Khatari Gaulden, who was killed in San Quentin on August 1, 1978. Black August expresses solidarity with these and other Black political prisoners and prisoners of war. It’s supposed to be a month of sacrifice and self-discipline. From the outset it was aimed at strengthening the Black freedom struggle, within and beyond the walls of prisons. It’s a commemoration, not a celebration. Mumia Abu-Jamal, who is one of the longest- standing political prisoners, called Black August “a month of injustice and divine justice, of repression and righteous rebellion, of individual and collective efforts to free the slave and break the chains that bind us.”

ESSENCE: Speaking of commemoration, your upcoming book, Organize, Fight, Win: Black Communist Women’s Political Writing, which you’re coediting with Jodi Dean, fills a large gap in the collection and recognition of works by Black communist women. In fact, it is the first historical work of its kind. Why do you think that gap has existed for so long?

BURDEN-STELLY: The only ones the United States probably hates as much as Black people—is communists. That’s just a historical fact. As I write elsewhere, knowledge or ideas or works that come from communist thinkers, writers and artists are considered unworthy of study, because the idea is that they’re just propaganda or they’re not “objective.” They are considered machinations of the Soviet Union or Moscow, or of China, or whomever else is the socialist enemy. When we have communists or radical figures, we either completely erase them or we try to sanitize them or liberalize them—to take one aspect of their ideas but subsume the rest, or to read them into some type of liberal framework. In a similar way, Black people have been construed as not having any history worthy of study, any reason or rationality. And that is even more so for Black women.

When we have communists or radical figures, we either completely erase them or we try to sanitize them or liberalize them

ESSENCE: How do you expect a project focusing on Black communist women to be received? What sorts of preconceived notions do you think this book will challenge for people?

BURDEN-STELLY: I just want to say their names. There’s Ella Baker, Charlotta Bass, Dorothy Burnham, Williana Burroughs, Grace T. Campbell, Alice Childress, Marvel Cooke, Esther Cooper Jackson, Thelma Dale Perkins, Tyra Edwards, Vicki Garvin, Yvonne Gregory, Lorraine Hansberry, Dorothy Hunton, Claudia Jones, Maud White Katz, Louise Thompson Patterson and Eslanda Goode Robeson. I think that on the one hand, the book will be well received because most of these women—with the exception of Dorothy Burnham—are dead. Most people will read it as an aspect of intersectionality that has moved into the mainstream. But it is not intersectionality. For radical Black people, it will offer up new resources about capitalism, labor, antifascism, anti-imperialism, organizing and a host of other themes. Or else it will probably be like one of those banned booklets, I guess.

In terms of what misconceptions this book may clear up, Marxism isn’t some Eurocentric sh*t. Black women were driving theoretical innovations in the Communist Party and were at the forefront of organizing. They were giving input. They were going to Moscow, attending these international meetings and contributing. They’re not just dupes of Moscow. They understood that to have an actual analysis of the working class—and of exploitation and imperialism—you had to engage the Negro question. Period. So, triple oppression. They talk about being oppressed as workers, as Black people, as women. We often conflate Black women’s intellectual traditions, rendering them monolithic. I emphasize the difference between triple oppression and intersectionality because they’re two different political genealogies. This work shifts the focus to a less-examined tradition and the anti-imperialist, internationalist, socialist women at its forefront.

This article appears in the July/August 2022 issue of ESSENCE Magazine

Source: Read Full Article