Singaporean director Anthony Chen’s English-language debut “Drift” world premieres in the Premieres section of the Sundance Film Festival on Jan. 22. Chen, the producers, and Cynthia Erivo, the film’s lead actor and one of producers, talk to Variety about the movie.

Starring Erivo (“Harriet”) and Alia Shawkat (“Arrested Development”), the film is from the producer team of “Call Me By Your Name” – Peter Spears, Emilie Georges and Naima Abed. Erivo, Solome Williams and Greece’s Heretic are also producers. Spears won the best picture Oscar for Chloé Zhao’s “Nomadland.”

“Drift” is based on Alexander Maksik’s 2013 novel “A Marker to Measure Drift.” It was a New York Times Notable Book, and finalist for the William Saroyan Prize, and Le Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger. The screenplay is co-written by Maksik and Susanne Farrell.

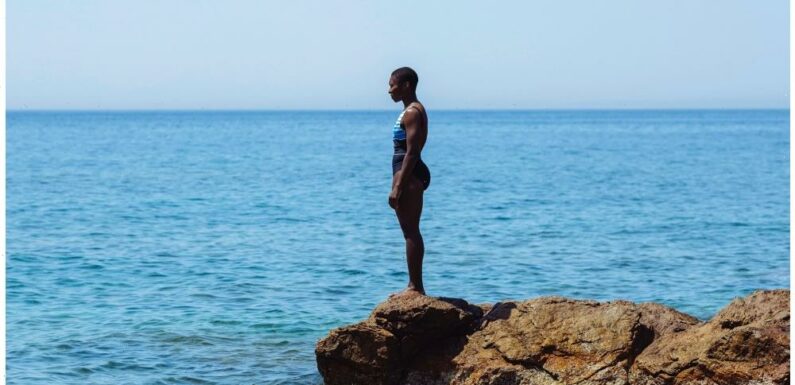

Erivo plays migrant Jacqueline, who lives a marginal existence on the shores of a Greek island, traumatized from war-torn Liberia, where her father was a government minister. Her life changes when she meets American tour guide Callie (Shawkat).

The sea is a constant backdrop – underlined by the opening shot, where we see a woman’s footprints washed away by the waves – highlighting the fragile existence of Jacqueline, who drifts on the cusp of existence.

Georges produced Chen’s first two feature films: “Ilo Ilo” (2013), which won the Caméra d’Or at Cannes and “Wet Season” (2019), which was nominated for the Platform Prize at Toronto Film Festival.

Chen, Spears, Georges, Abed, Williams and Erivo speak to Variety about the film.

Anthony, how did you become involved in the project?

Chen: Peter, Emilie and Naima approached me about this project in late 2018, with a very early draft of the script, written by Alexander Maksik. The first time I read it I thought it was based on a real character: the protagonist Jacqueline and the political and historical backdrop were so vivid. I was deeply moved but at the same time haunted by it. I’ve known Emilie since 2010; she was the sales agent for both my first and second film. I think they knew well my cinema and my sensibility. Jacqueline’s character and the story almost became an obsession for me. We brought on another screenwriter Susie Farrell, and I worked with her to develop it, mostly during the pandemic. We only began filming last March.

How did you bring your own vision to the project?

Chen: I was very lucky to have worked with Susie on the script. During the pandemic we talked almost every day by Skype. It’s a visual film, but all the details were on the page. And like all my films, it was important to bring the same honesty to the characters and the subject matter, in all aspects of the film. You see that in the script, the camerawork, the mise-en-scene. I’ve always been interested in these complex and intricate bonds and human connections between strangers. In “Ilo Ilo,” it was between a Filipino maid and a 10 year old. In “Wet Season,” it was between a teacher and a student. Here, in “Drift,” you have a Liberian Refugee and an American tour guide. Subconsciously, I think I tend to be drawn to such stories and such characters, perhaps because I’m an outsider myself. I’ve been living in the U.K. for 17 years, since I came here as a student. I still see myself as a migrant and I think that’s what gives me my perspective and objectivity when looking at a lot of things. When I go back and look at my work, it’s always about the outsider.

How would you describe the lead character, Jacqueline?

Chen: She’s a refugee but she comes from a place of privilege. I think both her mind and body are constantly adrift. She’s struggling to belong. She’s trying to define her very existence. This juxtaposition between privilege and chaos was evident in the novel and we tried to capture it on the screen. She’s like a ghost, sort of drifting around. She’s there, but doesn’t really belong. We read all these articles about migrants and refugees, but it’s hard to really understand the true human experience of what that really means. That’s ultimately why the film is so profoundly moving. I’m always slightly wary of films when there’s so much design behind; everything is calculated. You feel like people are banging on about social issues or political viewpoints. I find those films sometimes too manipulative or in a way exploitative.

Peter, could you explain a bit about the genesis of the project?

Spears: The book was originally optioned by Bill Paxton, a couple of years before he passed away. The novelist Alexander Maksik was working with him. Bill realized that it could make a beautiful and universal adaptation. My husband was Bill’s longtime agent and best friend. We were all at dinner after “Call Me by Your Name,” which he had just seen and really loved. He had recently met Cynthia and asked if I could help him produce it. He had admired the work that Emilie, Naima and myself had done together. He passed away a couple of weeks later, following heart surgery. I sometimes look back and wonder whether he was sort of getting his affairs in order, knowing it was going to be a serious operation. In honor of Bill, we’ve been shepherding it since then.

Immediately, I reached out to Emilie and Naima to see whether we could put this together as a European co-production. The very first person they thought of was Anthony. So, we met him and he met Cynthia, and they immediately hit it off. So, this kind of global village was created. Then we teamed up with our great producing partners from Greece, Heretic. Anthony was now the shepherd, to whom we could pass the baton.

Can you talk a bit about what Cynthia brought to the project, both through her portrayal of Jacqueline, and as producer?

Abed: You don’t know until you get on set, but she truly incarnated Jacqueline. She was a central element in this strange glue that brought us all together.

Williams: I think we all had our own perceptions of what the movie would be, what the character would be. Cynthia and myself started our journey as a production company two years ago, but even before she was in “Harriet” this was the movie in the back of her mind. So, when we joined forces and made it our mandate to normalize the experience of “the other,” this film resonated with that mission, both professionally but also personally. Cynthia is the daughter of Nigerian immigrants into the UK. I’m an immigrant, born at the height of war in Ethiopia in the 1990s; displacement is central to my own story. For us it was really about how do you give the layers and the textures to a character, to an experience beyond the headlines. She’s unmoored, she’s so adrift, unable to make a connection with another human being. And you feel she really starts to find her voice by the end of the film.

Chen: I think it wasn’t just Cynthia. I think every actor brought a lot of their own experience and I think that’s how this film had to be made. I’ve been constantly surprised by the decisions that Cynthia made on set and I go like wow – I didn’t see it on the page. I’ve always worked on films where I’ve written the scripts and I’ve seen it on the page. But when an actor comes in and inhabits a character completely and takes over, and you just see her blossom, you’re so moved. There have been a couple of times where I was moved to tears on set, because I think it’s a very brave, very generous, a very naked performance. I always believe in less is more and I try to pull back. There were moments where Peter had to remind me: ‘I think we just need more emotion here.’ I feel like it’s a very organic process – from the development of the script to how we shot the film and edited and finished it. The film had a life of its own. I’m really proud that we’ve been very faithful to the spirit and the sensualness of the book.

Emilie, could you talk a bit more about this organic process of making this film?

Georges: I think it’s clearly a post-pandemic film. It feels very relatable in the way that it’s part of a healing process in general. It’s something quite exceptional to maintain a process of understanding and compromise from people from so many different places, all with different visions.

Cynthia, summing up, why is this project so special for you?

Erivo: At first what drew me in was the humanity in the script and the character. It came to me while I was still on Broadway and moved me. When it came back a few years later, I had grown a lot and felt like I might have the capacity to help make the project. It was honestly like I had two brains, the hyper creative brain, connected to the character and her experience…and the pragmatic, organizational, problem-solver brain, whose purpose is to help facilitate the environment in which the story can be told. I’m lucky to have been part of a team of producers who held the reins on this just as tightly, because sometimes being both was almost impossible. There is however a quiet thrill in knowing that you have more to offer, which is listened to and acknowledged. You get to be a part of the process. That’s what I want – a holistic experience of the process of film and TV making. That was definitely this experience!

“Drift” is a co-production between France’s Paradise City Films (Georges and Abed), Greece’s Heretic (Giorgos Karnavas and Konstantinos Kontovrakis) and the UK’s Fortyninesixty, in association with Cor Cordium (Spears), Edith’s Daughter (Erivo and Williams) and Giraffe Pictures (Chen). It is financed by Sunac Culture and Aim Media, Ages LLC, the U.K. Global Screen Fund and the Greek Film Center, with support from Creative Europe. Memento International is handling sales.

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article