Two in every three souvenirs claiming to be Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander are fake, according to a wide-ranging report into visual arts and wares that calls on the federal government to create special laws to protect the copyright of Indigenous artists.

The Productivity Commission, in a report released on Tuesday, said Indigenous communities in some of the poorest and most remote parts of Australia were being denied vital sources of revenue from an arts and craft market worth at least $250 million.

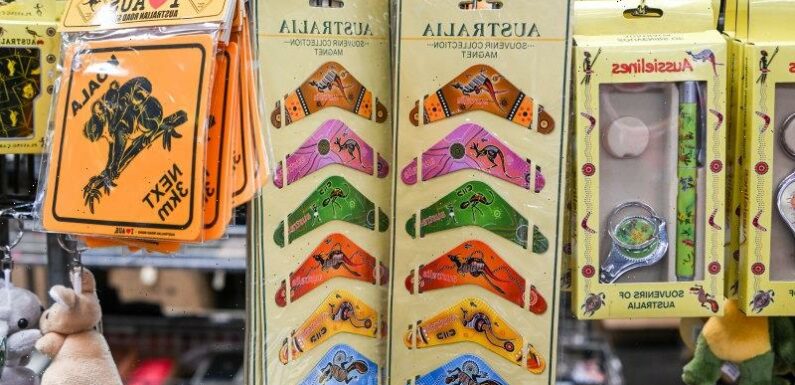

Two-in-three indigenous souvenirs are inauthentic, a Productivity Commission study shows as it calls for new intellectual property right laws.Credit:Justin McManus

The market has grown strongly over the past decade but Indigenous artists, particularly those in the APY lands of South Australia, Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory’s north-east and the Western Desert around across the NT and Western Australia, only make a small amount from their sales.

Of the $250 million total market, about 19,000 Indigenous people earned $41 million from the sale of their products. Up to two-thirds of this went to artists in remote areas, with incomes from sales averaging between $3200 and $7300 a year.

The commission found many sacred cultural symbols and stories were being misappropriated, causing economic harm and cultural offence to Indigenous communities.

Commissioner Romlie Mokak said a suite of proposals was needed to address the problems across the Indigenous art and craft market.

“Inauthentic Indigenous-style products mislead consumers, deprive Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists of income and disrespect cultures,” he said.

“Communities have limited legal avenues to stop their cultures from being used without permission and out of context.”

The situation is most acute in the $80 million Indigenous souvenirs market where domestic and international tourists are likely to be offered fake magnets, keyrings and boomerangs.

The Productivity Commission found that artists from remote communities such as the Western Desert earned very little from their work. Credit:Chris Beck

The commission found that terms such as “Aboriginal designs” or “handmade” were attached to products to create the impression they were authentic goods. Under current consumer law, such labels may not be illegal.

“The fact that manufacturers use such branding points to the value that consumers place on authenticity,” it found.

Prices for authentic and inauthentic coasters and magnets are similar, but the commission found huge differences between other souvenirs and goods.

An inauthentic didgeridoo has an average price of $45 while the average for an authentic didgeridoo is more than $230. An authentic bag has an average price of $22.50 compared to $6.20 for an inauthentic one.

On image websites showing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander designs, styles or motifs, more than 80 per cent of images were not Indigenous and over half came from overseas.

Among online print-on-demand websites, the commission found at least 60 per cent of listings were either not created by Indigenous artists or there were potential breaches of Indigenous artists’ works.

The commission, backing what it calls a multi-pronged approach, wants the federal government to put in place cultural rights laws that would formally recognise the interests of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.

Under intellectual property law, this would enable artists to take action against someone if they use a cultural asset, such as a piece of art, without the approval of a traditional owner.

Inauthentic products would have to carry prominent disclosures of non-Indigenous creation where a buyer might have a reasonable belief they were of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin.

Commissioner Lisa Gropp said mandatory disclosure of non-authenticity was a more practical approach than trying to ban inauthentic goods altogether.

“Mandatory disclosure where products are not made or licensed by an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander person would steer consumers toward authentic products and put the compliance burden on those producing fake products, not Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists,” she said.

The commission also backed a “modest” increase in funding to the Indigenous Art Code, which oversees a voluntary code of conduct covering artists and art dealers, so that it could improve its complaints and dispute process.

Cut through the noise of federal politics with news, views and expert analysis from Jacqueline Maley. Subscribers can sign up to our weekly Inside Politics newsletter here.

Most Viewed in Politics

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article