ZOE COLVILLE: I swapped a salon in Soho for nurturing orphaned lambs…but it was the animals that proved to be my salvation after my beloved father died

The pregnant sheep is feebly pushing and pawing at the ground. She’s tucked herself away in the corner of the top field, clearly in distress and close to exhaustion. I’ve spotted her on a walkabout to check on the progress of the expectant mums in our flock of 150 sheep.

As I climb the steep slope yet again, I’m thinking just how peachy my bum is going to get from all the outdoor exercise. I won’t be needing my gym membership much longer. But as I get closer to the ewe, my stomach plummets.

I recognise her — she’s a little Welsh Mountain ewe, small with an arched Roman nose, a soft thick fleece and a long fluffy tail, and we’ve been really looking forward to seeing her lamb. Although I’m only a part-time shepherdess, it’s obvious something’s going badly wrong for her. I grab my mobile and ring Chris — he’s my boyfriend, and right now he’s definitely the only experienced sheep farmer in our team of two.

‘OK, what exactly can you see, Zo?’ he asks me. As always, he stays calm.

I go around to the business end. Protruding out of her is a swollen lamb’s head, tongue hanging out, and a hoof.

I’m no farmer. I’m a hairdresser. Yep — that’s right. I work in a salon in Soho, Central London. On holidays and weekends I come down to Kent to join Chris on the farm.

ZOE COLVILLE: I’m no farmer. I’m a hairdresser. Yep — that’s right. I work in a salon in Soho, Central London. On holidays and weekends I come down to Kent to join Chris on the farm

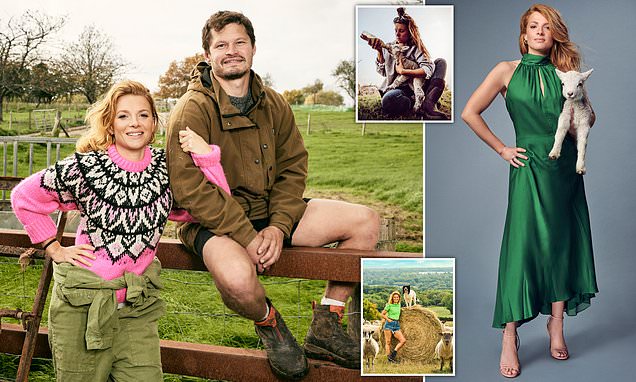

I DON’T come from farming stock. That was Chris (pictured together). We knew each other almost 20 years ago at school in Kent, but while we were growing up nothing happened between us

‘Can you help her get the lamb out? Can you pull it? Or get it in a better position?’ Chris asks me.

I look at the ewe. It’s lucky she’s small: I’ll be able to hold her comfortably. By the look of things, though, she’s got a very large lamb.

I tear off my T-shirt and drape it over her head, which I know will help to keep her calm, and kneel down to her in my sports bra and cut-off shorts — quite the Lara Croft look. Except that I’m not really Lara Croft. I’m just extremely out of my depth, half naked and on the verge of a panic attack.

‘OK,’ I say to her. ‘I’m kind of a novice here but I’m going to do my best. You’ve got this.’ I can only hope she finds my words encouraging. I decide that the best thing to do is to pull. I’ve seen Chris doing it.

I know I need to wait for her next contraction so that we’re working together. When I see her tummy clench, I use every muscle in my upper body as I haul at the lamb to try to bring it into the world.

‘That’s it, darling,’ I tell her. ‘Here we go. One last push.’

But nothing’s budging. The lamb seems stuck. Damn. I shift on to my backside alongside the ewe so that I can brace my legs against a tree. With that to push against, I can concentrate my force.

Suddenly the lamb is moving. With an enormous heave, it slithers out of the ewe, flops on to the ground and lies still.

I was crowned Chief Shepherdess. How serious could a hairdresser really be about the shepherding game?

I think it’s a bit stunned by its delivery experience. As am I.

Tears are streaming down my face. I frantically start rubbing the lamb’s tiny body. Once it’s wriggling, I pull it around to where its mother can see it.

Luckily, this ewe starts sniffing, then licking at her new arrival. She gives a throaty little beeeeh! and the lamb starts chatting back. Way to go, Mumma, I think.

By now I’m feeling like an absolute hero and I’m desperate to tell Chris. I grab my phone with gooey hands.

‘You still there? I did it! It’s been born!’ A little bit of me is expecting some kind of MBE for my performance. But that’s not my boyfriend’s style.

‘That’ll do, Pig,’ he says to me. It’s a quote from the movie Babe, and it’s about the highest praise I ever receive from him. Still, I can hear that he’s pleased.

Looking back, I can see that this was one of my first moments of questioning whether I’m truly cut out for farming and realising (as much of a surprise to me as to anyone else) that the answer might just be ‘Yes.’

I DON’T come from farming stock. That was Chris. We knew each other almost 20 years ago at school in Kent, but while we were growing up nothing happened between us.

Chris had crowned me ‘Chief Shepherdess’ early on in our escapades. It was just a private joke between the two of us

I’d left my home town of Maidstone at 18 to train as a stylist and colourist in London. Since my early teens I’d always fancied hairdressing. I loved the creativity and artistry of it, the sociability, too: helping people feel and be the very best they can.

For me there was nothing like the buzz of being right in the middle of the capital and having a brilliant time.

I changed my hairstyles and clothes often, and tried lots of different looks. I was experimenting, wanting to find out which of them was me.

When Chris and I got back in touch and started dating, a few years had gone by. Back then, he was a plumber in South London, commuting every day.

I started going down to stay with him at weekends, and now I found I enjoyed being back where he and I had grown up, going to country pubs and hanging out with our old friends.

Then, three months in, things suddenly got serious — only not in a good way. Chris was diagnosed with a virulent autoimmune condition, a form of ME, or chronic fatigue, which forced him to give up his job.

Racked with constant pain and living with his mum and stepdad, his confidence took a tremendous knock. He kept telling me forlornly: ‘This isn’t what you signed up for.’

The way I see it now, Chris never really chose to take up farming: he fell back into it as though he’d never left.

He’d began helping out on a neighbouring farm as he started to build his strength back. Then one day I took a call at the salon. ‘So . . . I may or may not just have bought a pen of Suffolk Mules,’ he told me.

I stared out of the window into Beak Street. ‘What the hell’s a Suffolk Mule?’ I enquired.

‘They’re sheep,’ he said.

‘And how many sheep have you bought?’

‘Thirty-two.’

‘Okaaay . . . so where exactly are you planning to keep them?’ It turned out he’d also rented a field. And that all the ewes were pregnant.

When I saw the sheep the following weekend, I could tell how excited Chris was. If this was what it took to bring purpose back into his life, I was happy for him.

I’d started off dating a plumber, and now here we were, rounding up sheep.

‘FETCH ’em in, then, Chief Shepherdess!’ yelled Chris. We were gathering in the wild ewes. The clue’s in the name. What a feral bunch they are.

I’d come straight from the salon that day in a little cotton smock dress with a Bardot neckline. Very Kate Moss at Glasto, I thought, as I’d finished off the look with my wellies.

Up until this point I’d always had a plan for life. Find a man, fall in love, buy a house, buy a dog, get engaged, married, pregnant, babies times three, live happily ever after, the end. But now we’d gone rogue

At this point there were some areas of life I definitely wanted to keep control over, and my wardrobe was one of them. So long as I still bore a vague resemblance to the old fashion-conscious Zoe, I didn’t feel like I was losing my whole identity in one hit.

Chris had crowned me ‘Chief Shepherdess’ early on in our escapades. It was just a private joke between the two of us.

I don’t think either of us imagined for one moment that it would ever become a reality. I mean, how serious could a hairdresser really be about the shepherding game?

The wild ewes showed zero inclination to go towards their pen. I tried a whistle and an arm wave, but they dashed off in a dozen different directions, running rings round me.

‘Why aren’t they flocking?’ I muttered, as one of them leapt over the fence into the next field as effortlessly as a gazelle.

Damn. What do I do? I scrambled after her. One foot on the wire, whip the leg over — and then I felt a sudden stabbing pain.

I should have known that there’s a very good reason why generations of farmers have all sported the same — expensive — brand of boots. It wasn’t long before I was plagued with agonising chilblains with multiple sores on every toe

A sharp line of barbed wire ran along the top of the fence and one of its spikes was embedded in my inner thigh. An inch shy of my knicker line, may I add.

I extricated myself carefully and clambered over.

Lesson One for a trainee shepherdess: Don’t wear cute little dresses. You’re not Bo Peep. I looked across at Chris, who was grinning from ear to ear as all this unfolded.

Lesson Two — and this was a big one: There’s no such thing as bad weather in farming — only the wrong choice of clothing. I’d dug out the old wellies I’d had since a muddy Reading Festival in my teens. What a faux pas.

I should have known that there’s a very good reason why generations of farmers have all sported the same — expensive — brand of boots. It wasn’t long before I was plagued with agonising chilblains with multiple sores on every toe.

So I caved and bought a pair of posh boots. I would’ve happily spent the same amount on a night out drinking cocktails in London without giving it a second thought.

So long as I still bore a vague resemblance to the old fashion-conscious Zoe, I didn’t feel like I was losing my whole identity in one hit

As the months went on, other new outfits began creeping into my wardrobe despite my determination to stay stylish — and they weren’t from glossy shops on Oxford Street, either.

They were overalls that don’t rip on the crotch in a week, thermal base layers that don’t go bobbly in the tumble-dryer and a waterproof jacket that has enough pockets for all the castration rings, needles and baler twine I could ever dream of.

How was this happening? My world was changing, and so was I.

‘HI, GORGEOUS!’ It was Chris. I was out for a boozy Saturday brunch with the girls, and two mimosas down, when the phone rang.

‘You’re gonna love me! I’ve got a surprise on board the trailer for you. Except — I think they might be die-ers.’

Die-ers? Who said romance is dead? My boyfriend had started bringing me half-dead lambs scooped up in a bucket during lambing season, or buying me a straggler from the market that no one wanted to bid for.

He knew that although I had no qualifications for it — I still don’t — I had really started to fall in love with the idea of helping ‘mend’ sick animals. I was discovering there’s no buzz quite like watching a ‘die-er’ — an animal that didn’t have much of a chance — out grazing in the sun.

Or, better still, when a comatose lamb sucks from a bottle for the first time. Watching a sick animal turn a corner and grow stronger and stronger is a better ego boost than just about anything else I can think of.

Fred and George Weasley were my very first patients — twin ginger Guernsey calves 11 days old, they looked like they were about to collapse at any moment. Being boys, they weren’t needed on the dairy farm where they were born. So they’d been sent to the market — and bought by Chris.

Watching a sick animal turn a corner and grow stronger and stronger is a better ego boost than just about anything else I can think of

I had about a million butterflies in my stomach as I rushed to the supermarket to get some baby steriliser, a whisk and a jug. Then I set about disinfecting the milk bar: a calf-feeding unit that looks like a trough with separate bowls and then a teat similar to the mother’s corresponding to each bowl.

The first two weeks they were around, I was certain they would die. They were too weak even to latch on to the milk bar so I had to let them slurp their milk out of a bucket — not ideal for their digestive systems.

But as long as they were getting some kind of nourishment, I crossed my fingers and carried on. By now I was fully invested.

A couple of weeks later, when they were growing stronger, I went to help a friend with her wedding hair. I drank plenty of champagne and had a wonderful time.

When I got back to the farm, I didn’t bother getting changed — just kicked off my shoes, slid my bare feet into my Wellingtons and headed out to check on my calves.

I’d only been with them for two minutes when Fred enthusiastically did his business down the side of my leg, straight into my boot. There’s nothing like the squelch of a cowpat round your toes to sober you up fast.

Fred and George were summer calves, which meant I could watch them in the sunshine, enjoying them as they gradually grew stronger.

And I knew that they had this chance at life because I had believed in them and worked to make it happen. It really did feel good.

We lost my adored Dad in the winter of 2018, just weeks after he’d been diagnosed with cancer, and my whole world fell apart. Grief. That word isn’t nearly huge enough to capture the myriad experiences within the process.

There’s no such thing as bad weather in farming — only the wrong choice of clothing

I’d taken time off work to help care for Dad and quickly grasped that going back to the salon wasn’t an option. I no longer had it in me to be sympathetic when my client was having a meltdown over little Archie spilling his Frube on her Range Rover seats. If my heart wasn’t in it any more, it was time to leave London for good.

Out in the fields, life carried on, because it does. The animals treated me just the same. And in the end they were my salvation.

Chris remembered how much I’d loved nursing Fred and George, so as we headed into winter he decided to give me a section of our rented farm that was wholly mine: a stake in our new life together.

On my birthday that October he surprised me with a new (second-hand) milk bar for calf-feeding — undoubtedly my best present ever. We bought a group of tiny calves and the preparation for their arrival was intense: building the pens in the shed, educating myself on calf nutrition and vaccinations. When they finally arrived I threw myself into it, skipping meals, working myself to the bone.

The grief and hurt that were pouring through my veins had to be soothed by something, and for me it was the calves. With their incessant mooing, I could no longer hear myself think, and an inner silence washed over me, like a massive wave of relief. Being with them became my therapy. I’d needed to find a route through grief, and they provided it.

Of course, choosing to work in one of the country’s most demanding and intense industries while suffering blinding grief might sound like a breakdown waiting to happen — and you wouldn’t be wrong: as a farmer you’re affected by every single life lost.

Saving lives and nurturing all the orphaned lambs brought a sense of usefulness and meaning

Picking up lifeless lambs from the field, or the stench of an animal that has died in the summer months — none of it is easy. But it’s part of the job. You soon learn that as a farmer, you have to focus on life.

As spring arrived at last, lambing became a real comfort. I felt at home when we were in the thick of it, a sense of belonging.

Saving lives and nurturing all the orphaned lambs brought a sense of usefulness and meaning. I’d been longing for that feeling. The living world around me had got me through my toughest winter.

Chris and I never had one big conversation when he said: ‘Hey, babe, come and be a full-time farmer.’ It just happened gradually. I didn’t make a grand announcement in the salon: I’m leaving to go and be a farmer!

As spring arrived at last, lambing became a real comfort. I felt at home when we were in the thick of it, a sense of belonging

But I did go back to complete my notice and say goodbye to my clients. Quite a few were struggling to imagine my new life and that was where the idea for my Chief Shepherdess Instagram account came in. I started it so they could see that I hadn’t invented the whole thing. Little did I know what would happen with that idea!

Up until this point I’d always had a plan for life. Find a man, fall in love, buy a house, buy a dog, get engaged, married, pregnant, babies times three, live happily ever after, the end.

But now we’d gone rogue. We were completely off-piste. Being a full-time farmer was never on my to-do list. While I was excited, the strategist in me was screaming: ‘SOS!’ So what happens now? What next? What about the Plan?

Could it work? Would it? I honestly had no idea.

- Adapted from The Chief Shepherdess: Lessons In Life, Love And Farming by Zoe Colville, to be published by Bantam on April 13 at £16.99. © Zoe Colville 2023. To order a copy for £15.29 (offer valid until April 22; UK P&P free on orders over £20), visit mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937.

Source: Read Full Article