For the first ten years of his career, Bill Nighy trod the boards in the U.K. He never saw a camera. He figured he’d be a theater actor for the rest of his life. In that time, just a few British stars were in the movies: Albert Finney, Michael Caine, Tom Courtenay, Peter O’Toole. “I was perfectly content,” he told me on Zoom. “I didn’t imagine I’d ever be on television particularly, or certainly not in a film. It was different times. My expectations were low, because I never expected to be an actor. And I never expected to be paid money for doing plays.”

Nighy’s world shifted when the late great casting director Mary Selway snuck him into a reading for Richard Curtis’ Christmas comedy “Love, Actually.” He got a couple of laughs. And landed the role of aging pop star Billy Mack, who records the unexpected breakout “Christmas is All Around.”

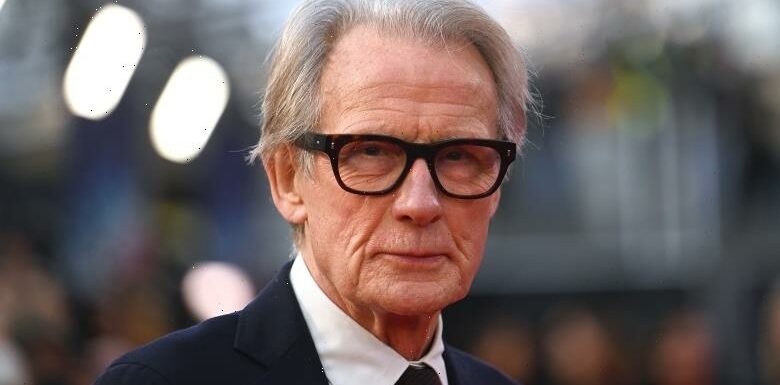

The 54-year-old’s life changed overnight. “I think it was a Trojan horse thing,” he said. “She thought, ‘Well, I’ll get him in the room. And we’ll see what happens.’ Anyway, I got the gig, much to my amazement, and they could have had anyone. I was reasonably familiar in England, but I wasn’t the kind of person you would give that part to, particularly in the context of that cast, with Hugh Grant, Liam Neeson, Emma Thompson, and everyone. So I was very surprised to get the part. It changed everything. It changed the way I went to work. And the most wonderful thing that any actor would tell you: it meant I never had to audition, ever.”

This year, things have changed again. After Nighy’s consistently successful career in theater (“Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia,” “Skylight”), television (“The Girl in the Café,” “The Man Who Fell to Earth”), and movies (“Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest” and “World’s End,” “The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel,” “Emma”), at age 73, the actor took on the lead role in “Living,” Kazuo Ishiguro’s adaptation of Akira Kurosawa’s “Ikiru,” which tells the story of Mr. Williams, an office functionary given a terminal diagnosis.

“Emma”

Focus Features

Ishiguro’s translation of Kurosawa’s story from 1953 Japan to 1953 England is hugely moving, as the shut-down Mr. Williams opens his eyes to the possibilities around him. And it could land Nighy his first Oscar nomination. The actor has been soaking up kudos and attention ever since “Living” debuted at Sundance 2022, and since then scored Golden Globe, British Independent Film Award, and Critics Choice Award nominations for Nighy, who won Best Lead Performance from the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. “Living” opened well in the U.K., before Sony Pictures Classics released it in theaters on December 23.

And it only happened because of a dinner that Nighy almost missed. “[Ishiguro] wanted to marry the message of ‘Ikiru’ with a kind of Englishness, which refers to a degree of restraint in one’s personal behavior, and a squeamishness about expressing anything emotional,” Nighy said. “Parallels have been made between that highly stylized form of personal behavior in England with that of a similar kind in Japan. They were not the same, but they were as elaborate and as formal as one another. So he wanted to marry those two things.”

Ishiguro played with the idea for a long time before he was persuaded to do the adaptation himself. But Nighy inspired the writer to move forward with this idea after meeting him for the first time. “I knew I was going to dinner with [producers] Stephen Woolley and Elizabeth Karlsen,” said Nighy. “And I knew that the other guest was Kazuo Ishiguro and his wife, Lorna. And all I knew about him was that he was a Nobel Prize-winning novelist. I came home from work, and it had been a long day. And I went and I lay down on the sofa and thought, ‘I’ll just have five minutes.’ And I woke up at half past nine with the phone ringing and Stephen said,’ You are coming?’ They were in North London and I was in Central and it took me an hour to get there.”

“Living”

Ross Ferguson

After that late dinner Ishiguro knew he wanted Nighy to play Mr. Williams, a deeply melancholy man in the 50s who is frozen in time in the 30s, when he lost his wife very young. “He has become institutionalized in that grief,” said Nighy. “And in that loss, it’s like he’s formed a cult of one. The idea that paid consultants have invented to shut us up is this thing called ‘moving on,’ which is largely mythical. But he has certainly not moved on.”

Before Nighy read the script, he watched “Ikiru” for the first time. Reading the script itself was “thrilling, it’s like, somebody read my mail,” he said. “I’ve always been lucky. I’ve been incredibly fortunate over the years with the people that I work with, but this has to go straight into top five if not number one spot. It is about living, all right? There is a man in it who is given a diagnosis, but it’s more about living than it is about dying. And people who’ve seen it, they’re galvanized by it, they’re inspired by it, they want to go out and make things happen, because that’s what the film is designed to inspire.”

The producers went to someone outside the British film community to helm the movie: biracial South African filmmaker Oliver Hermanus. “This is the first film he’s made outside of South Africa,” said Nighy. “We all saw ‘Moffie.’ Stephen had seen it at a festival and admired it. And it was his idea to attract Oliver.”

Hermanus saw a universal story, not confined to the tropes of Japan or England. “We’re all looking for meaning,” he said on the phone. “We find it in different things. Having children, changing careers, starting a business, dying one’s hair blonde. We ask ourselves, ‘what are we certain of in our lives?’ It’s hard to answer that.”

Woolley and Carlson “Living” boasted a reasonably small budget and a six-week shoot. “Most of the films that I’m involved in are British independent movies,” said Nighy. “Six weeks is pretty tight. It was a lot, but I was fascinated by the part. And I enjoyed it. It’s not a word I generally apply to my work. I thought I knew what I was doing. And that’s not always the case. It was full on.”

Hermanus describes Nighy’s process as “fraught,” he said on the phone. “Through that process he finds the character. We would spend a lot of time interrogating the screenplay, finding out who this man was. He memorizes the whole screenplay, his lines and everyone else’s lines. He’s the consummate professional.”

“Living,” starring Bill Nighy, 2022.

©Sony Pictures/Courtesy Everett Collection

When Mr. Williams gets his diagnosis, his first thought is to grab some money out of his bank account and go somewhere to eat, drink, and be merry. In Brighton he encounters a con man (Tom Burke) who helps him spend his money. “Mr. Williams has heard about this thing called a good time,” said Nighy. “And then he goes to Brighton to have a good time. But ‘hedonism failed the audition,’ which is a great [Ishiguro] phrase. And therefore he goes back.”

Mr. Williams “has this instinct that he’s missing something he can’t quantify,” said Hermanus. Getting to know his officemate Miss Harris [Aimee Lou Wood] launches a change. “She has a secret of life he’s unaware of, an ingredient he’s never tried.”

“Her vitality is infecting him,” said Nighy. “And because of the extremity of the situation and her vivid youthfulness, he is persuaded into expressing himself in a way that he probably never has with any other human being in his life. So that opens him up to some degree and kickstarts something positive, an atmosphere of positivity in him. And then it occurs to him, that there is a specific thing he can do to bring meaning to his life.”

Instead of moving papers from one pile to another, Mr. Williams sees a way to build something, to leave a lasting legacy. “He’s worked in a huge institution, which is more or less designed to say, ‘no, no, no,’” said Nighy, who cites the location County Hall as integral to the movie. “County Hall was unplugged by Margaret Thatcher years ago. It’s a huge monolith by the river. And it’s a marvelous location. And it’s perfect for what we wanted, which was a monument to procrastination and bureaucracy.”

Therefore Nighy finds himself at his peak, in his prime, as offers continue to pour in. “I used to think there wasn’t any version of my life where I didn’t do plays,” he said. “But I could imagine my life without plays. I’ve done them all my life. And it would have to be something irresistible, something you wouldn’t want to imagine someone else playing? And I don’t know what that would be. I don’t think of myself, anymore, primarily as a theatre actor. We’re not winding down. We’re cranking up the operation.”

“Living”

screenshot/Sony

Which suggests that Nighy was already committed to making the most of every minute of the day when he encountered Mr. Williams. “It was inspirational to be given a part of this power and beauty at this point,” he said. “But I was already involved in trying, like most people, to make the most of every day. It’s difficult, that irritating thing people say, ‘live your life,’ as if you live today as if it were the last day on your last day on earth — which no one can pull off, I can’t pull off. But I’m getting better, for a long time now. I’ve been trying to relish the beauty around me and try and find and stay on alert for that which is beautiful and that which is desirable, and not be persuaded into anything. Because I think I have an above average tendency to project negatively. So I’ve been vigorously resisting that for a long time.”

And he is inspired by others of his generation. “I saw David Hockney a few years back in November in Yorkshire, up a stepladder, and he had a pickup truck,” Nighy said. “He was painting a particular copse of trees and he was going to paint 50 canvases, which when put together would precisely fit the back wall of the Royal Academy. He was 75, and I thought, ‘I want to be like him.’ And every time I’m on YouTube, which I do most days of my life, I watch The Rolling Stones (the greatest rhythm & blues band the world has ever known). You look at Mr. Michael Jagger and Mr. Keith Richards and Mr. Ronnie Wood and think, ‘yes, there you go.’”

As far as Nighy is concerned, he has no intention of paying attention to what he is supposed to do at his age. “A lot of the way that they try and contain us has to do with marketing,” he said. “It’s like teenagers were invented by people so they could sell things to them: like, we’re supposed to at a certain point do this. Well, no, you don’t have to. There is no law against it. I’ve heard about retirement, but I don’t like what I’ve heard particularly. And the phone keeps ringing, so I’m beyond fortunate in that regard. And therefore, why wouldn’t I? ‘Let’s go to work.’ And also, the world has gone particularly crazy currently. So you get an opportunity to do things that might just even marginally help, or redress the balance. And I’m not saying that to be too grand about it, but why not? You’ve got to do something. Because there are dark forces abroad.”

Source: Read Full Article